The Daum vase of the Guimard’s bedroom

We begin a series of articles devoted to decorative objects outside of Guimard’s production but used by him to ornate both his furniture creations — on the occasion of an exhibition for example — or his own dwellings in the case of his private mansion on avenue Mozart. The identification of some of them was made possible thanks to a few rare photos published in magazines, but above all by the high-definition scanned photographs from the Cooper Hewitt Museum in New York and the collection bequeathed by the architect’s widow to the library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

On these documents, vases, statues, sculptures or everyday objects often decorate — sometimes in a surprising way — Guimard’s furniture. They have never really been the subject of an in-depth study as the attention is focused on the furniture itself (the inventory of which is still not completed…). Some of these objects are visibly contemporary with the architect, such as this vase we are studying today, others are of very different styles and periods, such as these statuettes of ancient inspiration which will be the subject of a future article.

But beyond this information which tells us about Guimard’s artistic tastes, we may wonder about the architect’s will to integrate so many objects so different to a style that bears his name and is known to be difficult to reconcile with other styles and even with other forms of Art Nouveau. The architect was certainly aware of the strong aesthetic personality of his furniture. Perhaps he wanted to prove that the Guimard style could nevertheless blend in with the objects in the decor of future buyers?

In the case of the decoration of the private mansion on avenue Mozart, another question soon arose: the delicate issue of the origin of the objects which did not belong to Guimard’s production. Some of these were certainly brought by his wife, but in the absence of additional information, it seems impossible to make a statement on this subject. This is perhaps the case of the vase from the Guimard’s bedroom that can be seen in the photos of that time.

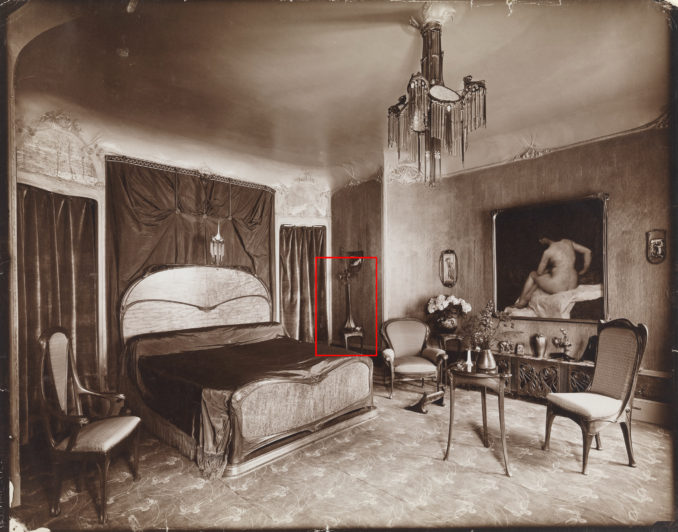

Its streamlined form makes it one of the objects that best suits the Guimard style and fits easily into the decoration of the room. It appears on two shots, placed on the same stand, in two different places in the room — to the right of the bed and near Mrs Guimard’s dressing table — probably the sign of several photographic sessions.

Bedroom of the Guimard couple, on the second floor of the private mansion 122 avenue Mozart in Paris. Private collection.

This vase presents strong similarities with a glassware of identical shape marketed by the Daum factory. Featuring a long stretched neck developed from a solid quadrangular base, the piece, about 70 centimetres high, retains its square geometric section, reinforced by a slight over thickness at each corner. These models, with their easily identifiable silhouette, are well known and Daum has created a range of about thirty different ornamentations, from hair ferns to sycamore winglets and representations of physalis or sailboats on a Mediterranean sunset.

Detail of another photo of the Guimard couple’s bedroom. Private collection.

Detail of another photo of the Guimard couple’s bedroom. Private collection.

In the sometimes surprising world of Art Nouveau glass lovers, it is not uncommon to refer to some of these vases by the strange term “berluzes”. The etymology of this denomination remains controversial and two hypotheses continue to oppose each other.

The first is that the term originated in the jargon of the workers of the old glass factories in the Saint Louis Les Bitche basin and refers to the vessel that allowed the staff exposed to the heat of the furnaces to quench their thirst. The object, known as a “berling”, usually made on site in a fairly rustic glass, most often had the appearance of a soliflore vase with a slightly bent neck into which, perpetuating the tradition of lemon balm water flasks, pieces of liquorice sticks were inserted to give the drink a more pleasant scent and taste. “Berluze” would therefore be a linguistic distortion of this original Moselle “berling”.

The other version, which is common among the families of employees of the famous crystal factory in Nancy, is that during the manufacture of one of the first soliflores of this type, a copy would have been so much askew that the “Père Daum” would have asked aloud if the glassmaker who had just made it had “la berlue” (i.e. had hallucinations)? This is obviously to be taken with caution, like many oral testimonies transmitted “according to family tradition”, as there is no evidence to corroborate anything.

Paradoxically, it is on a document from the archives of the Maison Majorelle dating from the decade 1890-1900 that we find the first mention of a “berluze” on the back of a photograph showing a carved and inlaid glass marquettry display cabinet decorated with numerous trinkets.

Black and white photo of a Majorelle collector’s furniture. Coll. author.

This soliflore is perfectly characteristic of the floral naturalist style that identifies the early productions of the Daum brothers.

Detail of the previous photo showing a “berluze” vase from Daum. Coll. author.

Photograph of the same vase with floral decoration with gold highlights on frosted backgrounds. Height: 34.8 cm. Private collection. Photo author.

“Berluze” Daum vase similar in shape to that of the Guimard couple’s bedroom, with maple decoration. Height: 68 cm. Sale De Baecque & associés on 30/01/2020. Photo De Baecque & associés.

Daum, large “berluze” vase in acid-etched multilayer glass with fern adiantum decoration. Height: 69 cm. Coll. part. Photo Henry’s sale house (Germany).

Usually, the engraved specimens offer a lesser thickness of the angular profiles compared to those made of marmoreal glass coloured by vitrification of oxide powders, known as “jade glass”.

Daum, two “berluze” vases with a square base in “jade glass” Height: 36 cm and 69,7 cm. Private collection. Photo author.

The more or less slender appearance of the vases actually depended on the height of each unit, which could vary by several centimetres from one specimen to another. They were made from a cast iron mould, but the rates imposed by the head of the factory hall meant that they were always taken out of the mould a little too early and, as their temperature was still very high during the de-stemming operation, the gravity and the relatively heavy weight of the pieces meant that they were sometimes likely to lengthen significantly.

Daum, base of a “berluze” vase with a square base in blue an green jade glass. Private collection. Photo author.

In parallel with these vases with a square base, Daum has also tried to produce like-minded creations on a triangular base, but these have not been as commercially successful.

Daum, large “berluze” vase in acid-etched multilayer glass with foliage and almond-tree catkins decoration, Height: 68 cm. Coll. part. Internet photo.

The long-necked soliflores quickly became a familiar figure in Art Nouveau style glassware. They are also found in glazed stoneware, for example at the Pierrefonds factory in the Oise region of France, with a model of modest dimensions and a more rounded base.

Pierrefonds vase in glazed stoneware, undated (circa 1910), signed “au casque” Height : 20,5 cm. Private collection. Photo F. D.

The vase from the Guimard’s bedroom does not appear in any of the museum collections that hosted the various donations from the architect’s widow. Moreover, even if one of the inventories of the contents of the Guimard Hotel made on the eve of the exile of the couple to the United States evokes “a small Daum vase”, it is unlikely that it corresponds to the vase studied today. It is therefore quite possible that it was given to relatives of the Guimard family when they moved or dispersed their collection.

Justine Posalski and Olivier Pons

Translation : Alan Bryden