Cremone bolts, locks and lever handles by Christian Eriksson

In September 2013, a pair of cremone bolt cases and handles (without top or bottom strike and without rod guide) was sold on eBay under the title “Pair of Art Nouveau silver bronze handles attributed to Hector Guimard (Van de Velde)”. As this reference to Henry Van de Velde was simply placed there to attract the attention of a more international audience, the question of attribution to Hector Guimard immediately arose. There were no known examples of these cremone bolts in any of his buildings, but the discovery of a new model is always possible.

Pair of cremone bolts. Sold on eBay 22 September 2013. Photo from the seller.

Most connoisseurs of Guimard had noted a certain similarity between these objects and his style, but had been put off by the somewhat too naturalistic aspect of the case, whose ends evoke leaves or flames. Nevertheless, the attribution to Guimard was not impossible because, on rare occasions, he placed in his compositions details taken directly from nature. And in the case of these cremone bolts, it was interesting to observe the emphasis placed on the handcrafted rendering of the material, reminiscent of that reserved for the porcelain doorknobs created for the furnishing of Castel Béranger and widely used by Guimard thereafter. Indeed, on closer inspection, the cremone bolt handle appears to have been roughly kneaded, as if clay strips had been pressed and turned on themselves by the modeller’s hand.

Pair of cremone bolts. Sold on eBay 22 September 2013. Photo from the seller.

The ends of the case are of the same type of work: their material seems to have been stretched and turned.

Pair of cremone bolts. Sold on eBay 22 September 2013. Photo from the seller.

As for the case, its central mass, smooth and curved like a core, seems to have been uncovered under a layer of clay that would have been rolled up at its four corners.

Pair of cremone bolts. Sold on eBay 22 September 2013. Photo from the seller.

But this visual aspect alone would not have been enough to grant them an attribution to Guimard, had it not been for the picture of a lot sold by Sotheby’s New York in 2005. This lot included two lever handles, as well as four handles of cremone bolt identical to those in the eBay advert, two reddish in colour (probably made of copper) and two in bronze or brass. It was immediately clear that the lever handles were the “long” version of the cremone bolt knobs.

Sales by Sotheby’s New York, on 10 March 2005, lot 224, attributed to Guimard, auctioned at 2400 $.

These six objects were then attributed to Guimard by the sale expert, which did not offer a great guarantee. A few years later, however, this attribution was confirmed when a pair of identical lever handles from the Josette Rispal-Lejeune donation in 2008 entered the Musée d’Orsay collections. The Musée d’Orsay put their photographs online, and their notice gave them as being by Guimard, without however attaching any bibliographical data. Given this information, there seemed little doubt that the cremone bolt sold on eBay could be attributed to Guimard.

Pair of “crutch-shaped door handles”, attributed to Guimard. Dimensions: width 13 cm, height 6 cm. Musée d’Orsay. Inventory numbers AOA 1742 1 and AOA 1742 2.

In addition, the eBay seller specified that his cremone bolt carried the “FT” brand that he gave to be that of the Thiébault (or rather Thiébaut) foundry, a Parisian art foundry essentially active in the second half of the 19th century. In reality, the “FT” brand is that of the Maison Fontaine, 181 rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, which specialised in artistic locksmithing. This brand had been acquired from the Fromentin company when it bought its stock.

Pair of cremone bolt. Sold on s-Bay 22 September 2013. Photo by the seller.

And the Castel Béranger portfolio clearly establishes that it was to Maison Fontaine that Guimard entrusted the publishing of the entire hardware of Castel Béranger, including the lock decorations, landing door knobs and lever handles. One could therefore imagine that Guimard had remained faithful to Fontaine for this model of cremone bolt.

Hector Guimard. Landing door knob, model of the Castel Béranger edited by the Maison Fontaine. Here photographed in the Jassedé building, 142 avenue de Versailles, Paris. Photo private collection.

However, by consulting several old documents and visiting the charming Fontaine Museum in Paris, one is quickly convinced of the contrary.

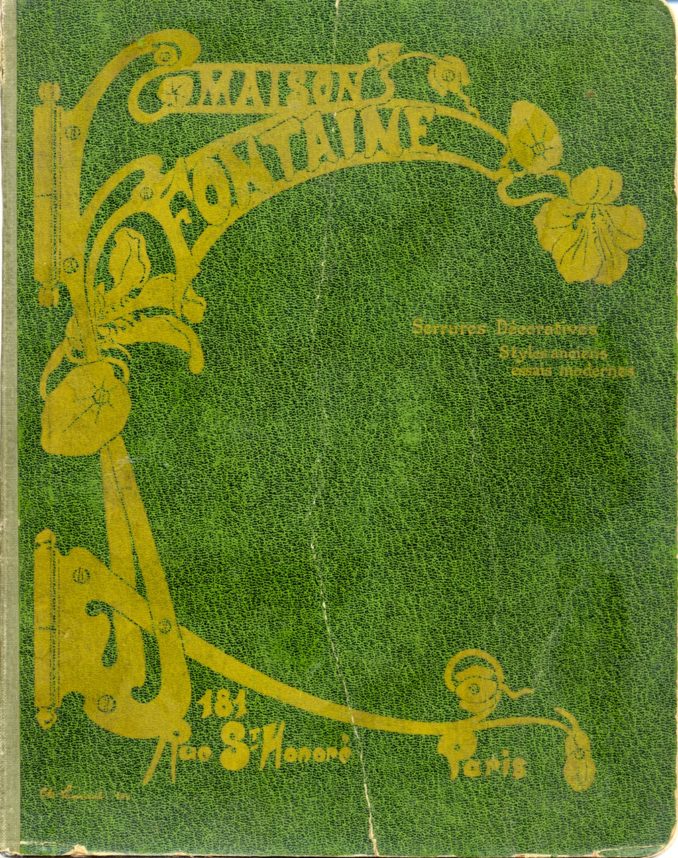

The first of these documents is a catalogue of the Maison Fontaine, published in August 1900 (probably on the occasion of the Universal Exhibition) entitled Decorative Locks/Ancient Styles/Modern Designs. It presents a large selection of photographic plates in which the names of some of Maison Fontaine’s collaborators are mentioned.

Cover of the Maison Fontaine catalogue. Decorative locks/antique styles/modern designs, August 1900. Private collection.

The second document is a portfolio, published by the Maison Fontaine at an unknown date (probably around 1900). Rather than a commercial document, it is a prestigious publication presenting some of the house’s most beautiful creations.

Portfolio Fontaine, date of publication unknown. Musée Fontaine.

Finally, some of the albums kept in the Musée Fontaine have a more clearly commercial function. They present the articles, classified by type of product, with their number and dimensions but without the name of their author or their date of creation.

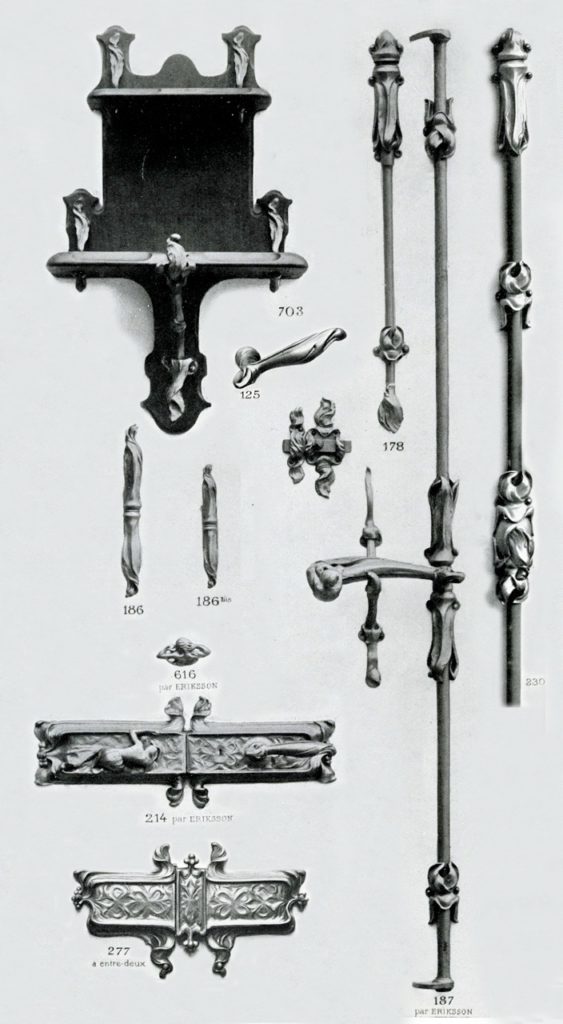

Indeed, from the first illustrated page (pl. 100) of the August 1900 catalog, the attribution to Guimard of the cremone bolts and lever handles falls to the benefit of Eriksson who is credited with a cremone bolt (no. 187, pl. 100), a knob (no. 616, pl. 100) and a lock (no. 214, pl. 100). However, several other items in the catalog to which his name is not attached can easily be attributed to him.

Plate 317 shows the famous cremone bolt (no. 230) with its top strike, top rod guide and top rail guide., similar to the ends of the cremone bolt casing, as well as its intermediate rod guide, which follows the pattern of the ends of the casing and is identical to the rod guide of the cremone bolt.

Also by analogy of the patterns, can also be attributed to Eriksson: a bolt (no. 178, pl. 100); a bolt (no. ?, pl. 100) ;

hinges (no. 186 and 186 bis, pl. 100 and 427); the metal decorations of a shelf (no. 704, pl. 100); an interlocking lock (no. 277, pl. 585).

Lock no. 277 from the 1900 Fontaine catalogue by Eriksson. Private collection.

as well as the lever handle mentioned above. The latter is in fact published in three widths: 120 mm (no. 125), 130 mm (no. ?), which is that of the Musée d’Orsay) and 142 mm (no. 314).

Eriksson, lever handle no. 125, width 120 mm. Auction Delorme – Collin du Bocage, 20 March 2014, lot 188, brand ” F.T “.

Eriksson, lever handle no. 314, width 142 mm. Private collection.

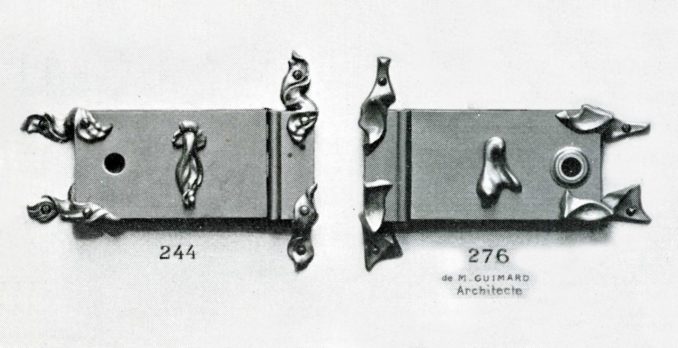

In the Fontaine catalogue of August 1900, we also find the names of Tony Selmersheim for articles that are still not very modern, and Alexandre Charpentier who inserts figurative bas-reliefs (as he created them in his initial profession as a medallist) on strictly rectangular or octagonal surfaces. Finally, there is mention of “M. Guimard Architect” who is only credited in this catalogue with a lock decoration (no. 276, pl. 585), that of Castel Béranger. On the same plate 585, another set of lock decorations (no. 244) is reproduced without any mention of the author but is easily identifiable thanks to the similarity of its legs to Eriksson’s bolt motifs. Its construction is identical to that of Guimard’s no. 276, with a simple parallelepipedal lock case and strike plate with no other decoration than the cover plate and the tabs that hold the strike plate and lock case together at its four corners.

Eriksson for no. 244 and Hector Guimard for no. 276, models of locks published by Maison Fontaine. Computer graphic montage based on plate 585 of the Fontaine catalogue, August 1900. Private collection.

Guimard opted for a rather simple and frank modelling of the elements where one can guess the modeler’s thumbprint, whereas Eriksson remained faithful to a more elaborate decorative work.

Guimard, attachments of a lock no. 276 from the Fontaine catalogue, August 1900. Private collection.

While in the Fontaine portfolio (a prestige document and not a commercial one), an entire plate is devoted to Guimard’s creations for Castel Béranger, his models do not appear in the albums of the Fontaine museum and are not kept in the collections of the Fontaine house. It is therefore likely that, apart from the lock, Guimard, who had already published them in 1898 in the Castel Béranger portfolio, wished to keep the exclusivity.

But who is this Eriksson who seems to have left so few traces in French decorative art? He is the Swedish sculptor Christian Eriksson (Taresud, 1858 – Stockholm, 1935), famous in his country and internationally trained. Nine years older than Guimard, he attended the same Parisian art schools as him, during the same years. Our Swiss correspondent Michel Langenstein provided us with a biographical note from the catalogue published in 2008 by The Dansk Museum of Art & Design in Copenhagen. It notably enriches that of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. We also draw information from his Wikipedia entry published in Swedish.

Christian Eriksson. Silver jewellery box depicting a little girl immersing herself in an overflowing pool, framed by a male and a female figure. 1897. Dimensions: width 16.5 cm, depth 7.2 cm, height 9.5 cm. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.

Christian Eriksson was born in Taresud in the county of Värmland in Sweden, in an environment devoted to agriculture and woodworking. As a child, he worked with his father, the cabinetmaker Erik Olson and his brother Elis Eriksson, who would later become a cabinetmaker. As a young man, he apprenticed with an ornamentalist in Stockholm while attending a technical school. From 1877 to 1883, he worked as a furniture designer and model maker in a factory in Hamburg, where he also attended a school of craftsmanship and design. In 1883, he travelled, working in various workshops in the Rhineland and ended up in Paris where he enrolled at the School of Decorative Arts, then at the Beaux-Arts School in 1884, in the workshop of the sculptor Alexandre Falguière. In 1886, he made his debut at the Salon and made a name for himself in 1888 with the sculpture Le Martyr, which earned him a medal and a scholarship. He also received furniture commissions, built a house in Taresud, the town of his childhood, while travelling frequently between Paris and Värmland from 1894 (when he married the Frenchwoman Jeanne Tramcourt) to 1898, and finally settling in Stockholm. In 1902, he first addressed the theme of Sami culture with the sculpture The Laplander.

Christian Eriksson. Sitting Laplander, 1909. Sale Bukowskis, Stokhlom.

From 1903 to 1908, he is in charge of the decoration of the facade of the Stockholm Royal Drama Theater.

Christian Eriksson, photo portrait, as of 1904. Taken from the Wikipedia note dedicated to Eriksson.

Having thus experienced the early years of French Art Nouveau, practising monumental as well as decorative sculpture with small bronze and silver vases and cups, he did not disdain to offer his assistance to art industrialists, notably through this important collaboration with the “modern essays” of the Maison Fontaine. His more usual figurative style appears on several pieces of hardware, such as lock no. 214.

Christian Eriksson, lock no.214, La Curiosité (Curiosity), with the lever handle no.125. Musée Fontaine.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214, La Curiosité (Curiosity), with the lever handle no. 314. Private collection.

The female figure that seems to spy through the keyhole gives it its name La Curiosité (Curiosity) and links it to the late Symbolist movement, like the door handle – letterbox La Renommée (Fame) modelled by Victor Prouvé for the door of the house of the Nancy carpenter Eugène Vallin in 1895.

Eriksson, lock n° 214, La Curiosité (detail). Private collection

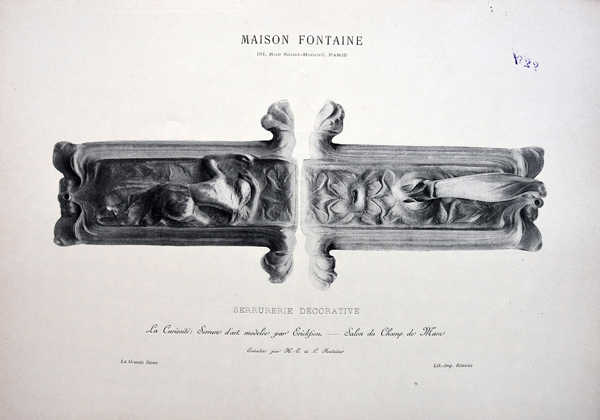

Sign of its importance, a plate of the Fontaine portfolio is dedicated to it.

Christian Eriksson, lock no. 214 with lever handle no. 125. Mention “La Curiosité”; Art lock modelled by Eriksson – Salon du Champ de Mars”. Plate from portfolio Fontaine, date unknown. Fontaine Museum.

The right-hand side of the lock, with the lever handle, can be found on the doors of two of the three lounges created by the Nancy native Louis Majorelle for the Café de Paris (41 avenue de l’Opéra) in 1898, which gives a better idea of its creation date. The following year, when Henri Sauvage was entrusted with the fitting out of two additional salons, he used locks that were more commonplace and less well integrated into the joinery.

Door of one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris, avenue de l’Opéra in Paris, in 1898. The door is closed by Eriksson’s Fontaine lock no. 214. German Portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

At the Universal Exhibition of 1900, this lock no. 214, La Curiosité, was presented with doorknob no. 616 (Woman coming her hair) by the Maison Fontaine, along with figurative works by Gustave Michel and Louis Bigaux. The Museum of Art and Design in Copenhagen has a silver version of this doorknob.

Christian Eriksson, door knob no. 616, Woman coming her hair, bronze with traces de gold coating. Private collection.

The handle of the cremone bolt no. 187 is quite astonishing. Seen from a distance, it is reminiscent of the end of a bone and thus the sarcasm of the art critic Arsène Alexandre in Le Figaro of 1 September 1900, who asserted that the “noodle [had] compromised itself with the sheep bone to make up what has been called the generic, and bizarre, name of art nouveau”.

Eriksson, cremone bolt no. 187. Portfolio Fontaine, unknown date. Musée Fontaine.

But a closer look at its tip reveals that it is a small figure that seems to weigh its full weight to keep it closed.

Eriksson, cremone bolt no. 187 (detail of the handle). Musée Fontaine.

On the other hand, the hinges, the bolt, the cremone bolt and the rod guides of the cremone bolt are closer to the naturalistic current of Art Nouveau by their evocation of rolled up leaves.

Christian Eriksson, strike and rod guide for cremone bolt no. 230. Catalogue Fontaine, August 1900.

catalogue Fontaine août 1900

doc transmis par Dominique Magdelaine

However, as mentioned above, the details of the cremone bolt handle and the crutch introduce a completely new way of giving the modeller’s gesture a new look by not hesitating to display a deliberately unfinished appearance. There is a real parallelism here with the work of Guimard’s early years, whose modelling took on a “crumpled” and somewhat wild appearance before he made it evolve quite rapidly by favouring the harmony of lines and the elegance of the composition.

Finally, thanks to our German correspondent Michael Schrader, who opportunely reminded us of this, we should mention the presence of Eriksson’s cremone bolts in the windows of the very beautiful the town hall of Euville village in Meuse, decorated (or rather internally lined) in 1907 by Eugène Vallin. The author of several models of hardware to decorate his joineries and furniture, Vallin did not have his own model of cremone bolt. In this case, he used the catalogues of Parisian manufacturers.

Cremone bolt by Christian Eriksson from a window in the town hall of the Euville village. Installed in 1907 by the Nancy carpenter Eugène Vallin. Photo Cédric Amey. Nancy-guide.net.

Frédéric Descouturelle

in collaboration with Dominique Magdelaine and Olivier Pons.

Translation Alan Bryden

Many thanks to the collectors who have allowed us to reproduce their objects and provided us with information, as well as to Mrs Christine Soulier, Head of Decorative Locksmithing at Maison Fontaine.