Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique in 1897 and other architectural achievements in glazed ceramics

Our previous article showed that the ceramic decorations at Castel Béranger are only partially attributable to the Bigot company, which specialized in glazed stoneware. By looking at a contemporary creation, that of the stand presented by Guimard at the Exposition de la Céramique in 1897, we continue to clarify the roles of the ceramic companies that Guimard called upon, the role of the modellers who assisted him, and the nature of the products of their work (stoneware or terracotta). Some ceramic decorations made in the filiation of those of Castel Béranger, but for other constructions, will also be mentioned.

The panel with the cat arching its back which we presented previously can be found (probably before its final installation on the Castel Béranger) included in Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique et de tous les Arts du feu[1] in 1897.

Panel with the cat arching its back, c. 1897, glazed ceramic by Gilardoni & Brault, placed under the oriel on the left corner of the second floor of the building on street. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

This exhibition mixed all the products of ceramics (and glassware) whether they are building materials, technical materials or artistic expressions. For the latter, in addition to the indispensable retrospective section, we find the names of those who will soon express themselves in a remarkable way in the modern style: Bigot[2], Lachenal, Delaherche, Massier, Dalpayrat, but also larger and more industrial companies with necessarily eclectic productions such as Loebnitz, Keller & Guérin, Muller, Gilardoni & Brault[3]. Of course, the Manufacture de Sèvres is widely represented[4].

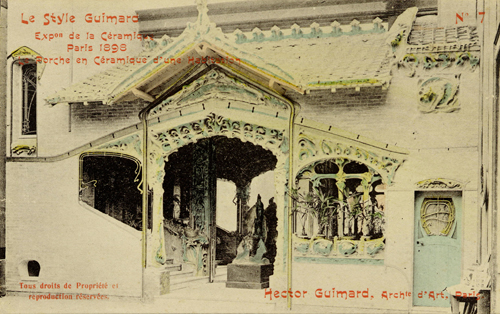

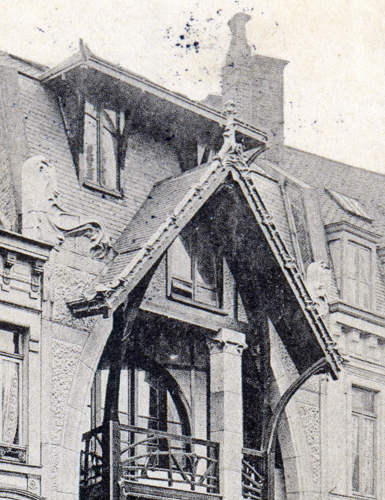

The only picture we have of the Guimard stand is on one of the postcards of the series Le Style Guimard[5] .

Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique et tous les Arts du feu in 1897: “Ceramic Porch of a Dwelling”. Old postcard n° 3 of the series Le Style Guimard, wrongly dated 1898. The cat arching its back is on the top right. Private collection.

Since the Parisian public could only then incidentally know of the existence of the Castel Béranger under completion, this stand was the first public manifestation of Guimard’s modern style and certainly caused a visual shock by its radically innovative aspect. More than just a stand, this presentation is a true architectural achievement presenting a building porch[6] leaning against a blind wall decorated with mirrors. Its walls are made of brick and Guimard, by adding an awning to the tiled roof, has deployed an important combination of ridge, cornice and tympanum which surmounts the rich framing of the openings with clerestory, including a mullioned window and window box in the lower part. The decoration continues inside with a console and pilaster at the start of the staircase, panelling that accompanies the ascent of the steps and probably a ceiling.

Given that, apart from the panel of the cat arching its back, no other decoration is a duplicate of those of Castel Béranger, one may legitimately wonder whether the name “porch of a large Parisian dwelling” might not lend credence to the idea that this is a project intended to be at least partially integrated into a real building and not to be destroyed after the exhibition. However, no plan, no other image, no information supports this assumption. It therefore seems more logical to think that it is indeed an ephemeral construction and that Guimard had his stand financed by a major company. Company A. Bigot & Cie was then at the very beginning of its existence and probably did not have the means for such an expense leading to the promotion of a single architect. It could only make the effort of a well-placed, but fairly small, stand.

On the other hand, the company Gilardoni & Brault, could be served by such a presentation which mixed its usual production of glazed tiles and bricks with a stunning decoration modeled in architectural ceramics demonstrating its perfect mastery of the material and its adherence to the most modern stylistic trends. In fact, it had already shown an interest in the artistic sector since, two years earlier, it had collaborated with the famous ceramist Edmond Lachenal during his annual exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit. At that time, the artist had called upon Gilardoni & Brault to pane a Gothic-style dining room with grand feu earthenware. The same Lachenal[7] was also found in 1897, occupying one of the main stands at the Exposition de la Céramique.

In the catalogue of the 1992 Guimard exhibition at the Musée d’Orsay, Philippe Thiébaut[8] indeed gave the Guimard stand as being “entirely executed by […] the Maison Gilardoni et Brault”. But in his book Guimard, published in 2003, Georges Vigne[9] thought on the contrary that the location of Guimard’s stand “just behind Gilardoni & Brault’s stand” had created confusion and that this stand was the creation of the architect alone who had certainly used Gilardoni & Brault’s glazed bricks but in fact presented decorations executed by Bigot.

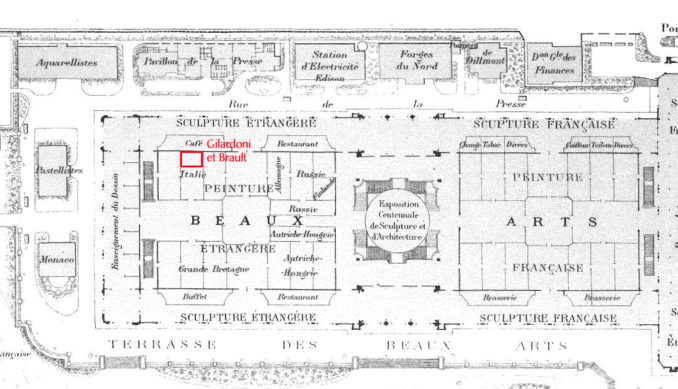

What is the reality of the situation? One only has to look at the floor plan of the Ceramics Exhibition to dismiss any ambiguity. The Gilardoni & Brault stand is located against the north wall of the Palais des Beaux-Arts.

Fictitious location of the Gilardoni & Brault stand in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in 1897, placed on a floor plan of the 1889 Universal Exhibition. The Seine is on the left, the Eiffel Tower at the bottom left and the Avenue de la Bourdonnais above. Internet illustration.

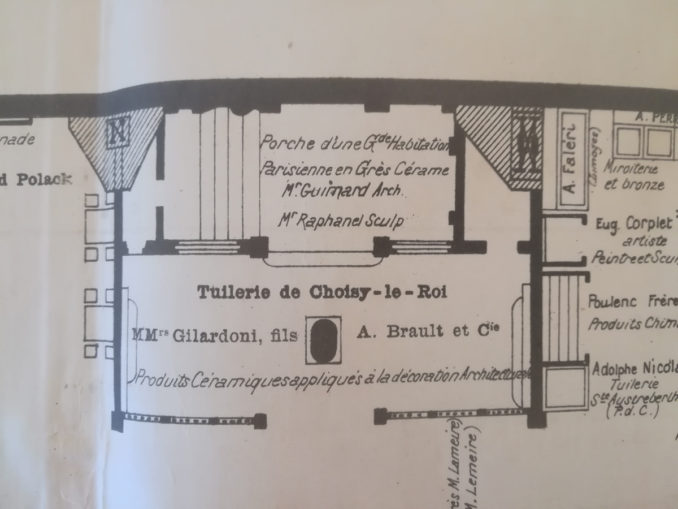

The floor plan of the Exposition de la Céramique[10] clearly shows that Guimard’s porch is not behind that of Gilardoni & Brault, but within it.

Floor plan of the Exposition de la Céramique et de tous les Arts du feu (detail), 1897. Library of Decorative Arts. Photo Olivier Pons.

In fact, it makes up almost all of it, since the rest of the material exhibited by the Choisy-le-Roy tile factory is relegated to two thin shelves placed against the side walls. One of them can be guessed, surmounted by a round dish, to the right of the postcard Le Style Guimard. The plan also indicates the presence of a pedestal receiving an important piece, placed in the center of the stand. It is probably the figure perched on a sphinx head that was moved under the porch for the purposes of the photograph. It adds a decorative, historicizing note and reminds us that Gilardoni & Brault also published reproductions of sculptures. It is likely that the partitions that partially close off the stand along the aisle also played a role in presenting the products of the tile factory.

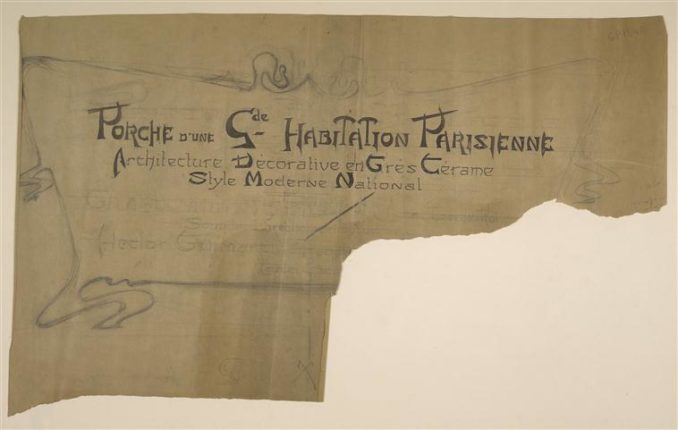

The way in which the names and credentials of Guimard and Raphanel are shown on an equal footing on the floor plan (in smaller size and in italics) clearly shows that they are for Gilardoni & Brault (mentioned in bold) two collaborators. If Guimard had had complete control of the porch project, he would have had his name put forward and would have mentioned those of Gilardoni & Brault and Raphanel more discreetly. Moreover, on his stand sign project, he presented the realization as under his direction.

Project for a sign for the Gilardoni & Brault stand at the Ceramics Exhibition in 1897. Porch of a Large Parisian dwelling in glazed stoneware/Architecture Décoratif en Grès Cérame/ Style Moderne National/par/Gilardoni Fils et A. Brault Tuilerie de Choisy le Roi/under the direction of…/Hector Guimard Architect…/… Ink and graphite on tracing paper, Musée d’Orsay, Guimard collection, GP 1840.

And six years later, on his postcard from the Le Style Guimard series, he concealed the name Gilardoni & Brault and rose from collaborator at the tile factory to project manager and even stand owner. Due to the distribution of this card and the scarcity of other information, this version prevailed afterwards.

However, if need be, a source that has not yet been cited confirms that it was indeed Gilardoni & Brault that took the initiative for this stand. The magazine La Construction moderne, in its editorial of 5 June 1897, announces the recent opening of the Ceramics Exhibition. In a quick overview of its organization and exhibitors, the article points out “the products of the Choisy-le-Roi tile factory with the porch so original by Messrs. Gilardoni and Brault.” And in a second, more precise article, published on August 28, we find this enlightening paragraph:

La Construction Moderne, 28 August 1897, p. 569. Quote from the site Gallica.

Like the exhibition floor plan, this press article quotes the name of the little-known young sculptor Raphanel[11] . We find him in the list of players at the Castel Béranger, alongside another older and better known sculptor, Ringel d’Illzach[12] .

Photomontage by computer graphics of an excerpt of the plate from Castel Béranger’s portfolio containing the names of the people and companies that executed the models.

By “Exécution des modèles de sculpture” (Execution of the sculpture models), we must undoubtedly understand the execution of all models in relief, whether they are stone sculptures, staffs, cast iron or ceramics, which require the work of a modeler. At a time when Guimard did not yet have his own workshop and craftsmen, the creation of all the models necessary for the decoration of Castel Béranger was so immense that it is not surprising that he was assisted. But how far did the intervention of these two sculptors go, who are above all independent artists and not mere practitioners? It is difficult to determine whether they were able to introduce some of their own creativity into the elaboration of these models or whether they had to be satisfied with a more summary work consisting in translating Guimard’s drawings into three dimensions, whose style, made of a crumpled, bubbling material, was quickly integrated before soon becoming more orderly and harmonious.

In support of the first hypothesis, Ringel d’Illzach’s work includes numerous masks and a certain proportion of monstrous figures such as those found on the masks on the balconies of Castel Béranger.

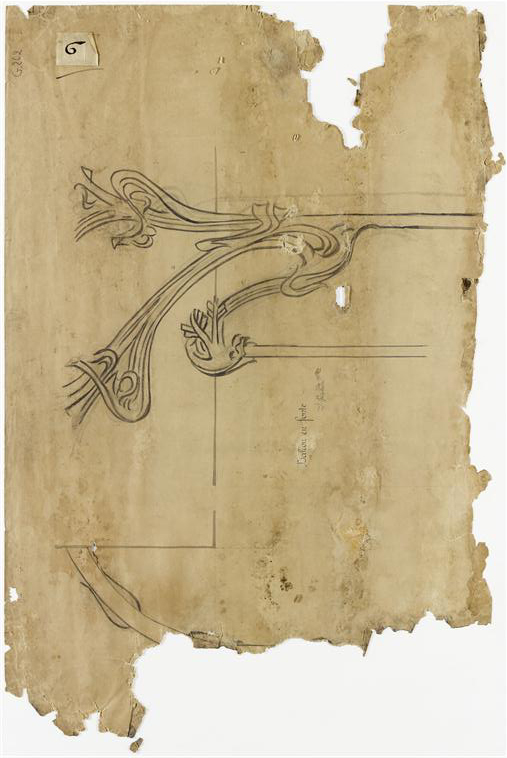

In support of the second hypothesis, we find in the portfolio of Castel Béranger, above the list of the various contributors, the following statement: “The plans, architectural and decorative drawings (Sculptures, Ironwork, Mosaics, Stained Glass, Fireplaces, Wallpapers, Drapes, Coatings, Stoneware, Earthenware, Interior Furnishings, Bronzes, etc.) that make up the “Castel Béranger” were composed by Hector Guimard, and are his property”. One of the few known designs of one of the cast irons of Castel Béranger, that of a crossbar support, also points in the direction of a supervision of the models by Guimard because this design was faithfully translated into three dimensions. However, it can be seen that the modeller has retained a certain margin of initiative in the detail, which has resulted in an enrichment of the relief.

Drawing of the Castel Béranger’s left crossbar support. Musée d’Orsay, Guimard collection, GP 262.

Crossbar support of a window of Castel Béranger. Cast iron. Photo Author.

It is also not very easy to determine the part devoted to each of the two sculptors in the decorations of Castel Béranger. Georges Vigne[13], on the basis of the participation of Raphanel alone at Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique, attributed all the ceramic models to him and gave the cast iron models to Ringel d’Ilzach. This distribution is the most probable, even if it is probably not absolute and does not settle the question of the stone sculptures and the staffs either.

It remains for us to determine the exact nature of all this architectural ceramic decoration. The question arises insofar as, in 1897, if Gilardoni & Brault could produce stoneware, the company would only begin its industrial marketing after 1900 and Bigot’s success at the World Exhibition. We have seen that for Castel Béranger, we could suspect that it delivered glazed terracotta. But for the stand at the Ceramics Exhibition the answer seems to be glazed stoneware. Even if the postcard (six years later) mentions a “Porche en Céramique” (Porch in Ceramics) and if the article in La Construction Moderne mentions a porch “made entirely of ceramics” without using the term stoneware, it is indeed the name of the latter material that comes back insistently on the exhibition floor plan as well as on Guimard’s sign project. They both mention a “Porch of a large Parisian dwelling in porcelain stoneware”[14].

Other architectural achievements in glazed ceramics

These spectacular decorations that have largely blossomed on these two achievements will have a rather small offspring. We will find similar ones on the lintels of the Villa Berthe at Le Vésinet (1896). Once again a moving, but more orderly, material seems to be contained by iron blades that have now left the orthogonal rigidity that we saw in the Hotel Jassedé and the vestibule of Castel Béranger, to soften and bend. Without any document from the time and (probably) without a signature on the ceramic panels, it is currently imprudent to attribute them to any of the ceramic companies with which Guimard worked until then.

Villa Berthe (1896), lintel of the first-floor window of the central bay of the main façade. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

Villa Berthe (1896), lintel of a first-floor window in the side bays of the main façade. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

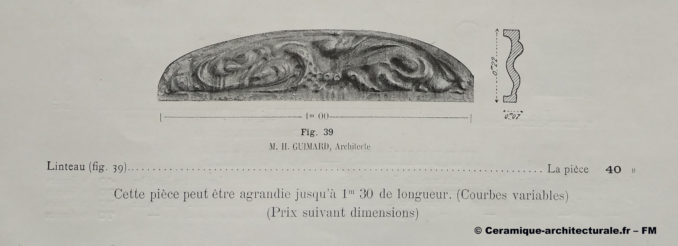

On the other hand, a small lintel with rounded ends is easier to assign. It has the same fingerprints as the panels in the vestibule of Castel Béranger (supplied by Bigot) and we are certain of its edition since it appears in Bigot’s 1902 catalogue.

Lintel by Guimard, catalogue Bigot, 1902. Coll. Françoise Mary. Photo © Ceramique-architecturale.fr.

In a standard length of 1 m, it is sold 40 F-gold, but it can be enlarged to 1.5 m. Guimard will have two copies inserted on a facade of the small courtyard of the Hotel Deron Levent in 1907.

Courtyard of the Deron-Levent Hotel (1907). The glazed stoneware lintels are placed above two first floor windows (here the bathroom window). Photo by the author.

Later, during the expansion work at Castel Val in 1911, Guimard would decorate the long wooden railing of the terrace joining the house to the garage.

Balustrade of the terrace of the Castel Val at Auvers-sur-Oise (1902-1903) built in 1911. The element photographed is a cement copy (as is the balustrade), but two glazed stoneware originals are preserved. Photo Nicolas Horiot.

Glazed stoneware lintel edited by Bigot, originally inserted in the balustrade of the terrace of the Castel Val in Auvers-sur Oise (1902-1903) built in 1911. Private coll. Photo author.

This lintel edited by Bigot seems close to two other modeled lintels but which are actually different from it. One is placed above the service door on the right side of the “Porch of a Parisian dwelling” of 1897 (by Gilardoni & Brault). The other, in three parts, is in Guimard’s architectural office at the Castel Béranger, where it surmounts the door separating the study from the small room overlooking the Béranger hamlet (below). This last lintel, enclosed in metal angle irons, is probably made of stoneware like the others but could also be made of glazed lava.

Linteau d’une porte du cabinet d’architecture de Guimard au Castel Béranger. Détail de la carte postale ancienne n° 10 de la série Le Style Guimard. Coll. part.

A very original roof ridge is positioned on the roof of the Norman villa La Bluette in Hermanville-sur-mer. It is tempting to attribute it to Gilardoni & Brault, who were manufacturers of roofing accessories, rather than to Bigot, who did not offer any in its catalogue. But we are not sure about this. It is also possible that this decoration was ordered locally from the Poterie du Mesnil de Bavent which specialised in this type of product.

Roof and ridge of the villa La Bluette in Hermanville-sur-Mer (Calvados). Photo François Levalet.

The original decoration (no longer existing) of the awning of the Coillot house in Lille (1898) is close to that of the porch of Guimard’s stand at the 1897 Ceramics Exhibition, which also has a finial. It can therefore safely be attributed to Gilardoni & Brault.

Awning of the Coilliot house in Lille (1898). Old postcard n° 15 of the series Le Style Guimard, uncolored version. Coll. D. Magdelaine.

Frédéric Descouturelle in collaboration with Olivier Pons

Translation Alan Bryden

We thank Ms. Françoise Mary who provided the extract of the 1902 Bigot catalogue.

[1] The Exposition Nationale de la Céramique et de tous les Arts du feu (National Exhibition on Ceramics and all the Arts of fire) was held at the Palace of Fine Arts on the Champ-de-Mars from 15 May to 31 July 1897 and was extended until 5 September. This was the last exhibition organised in this building built by the architect Formigé (1845-1926) for the 1889 Exhibition. The building was demolished just after the extension of the Ceramics Exhibition to make way for the new palaces due to host the 1900 Exhibition.

[2] Alexandre Bigot (1862-1927) is a chemist by training. He founded his company in several stages from 1893 onwards, which he established in Mer (Loir-et-Cher) and concentrated on the production of glazed stoneware, unlike the Muller and Gilardoni & Brault companies, which produced glazed tiles, bricks and terracotta at the same time. It developed rapidly, receiving orders from many architects and publishing the creations of many artists, to reach an industrial dimension from 1897. Three years later it triumphed at the Universal Exhibition in Paris and competed very seriously with Muller, for fame among the supporters of the modern movement.

[3] The company Gilardoni & Brault, in Choisy-le-Roy, is the offspring of the Garnaud company, active since the middle of the 19th century and known for its architectural terracotta imitating carved stone. Alphonse Brault took over the company in 1871. He had previously made the acquaintance in Alsace of Émile Muller, with whom he was to become head of production, and Xavier-Antoine Gilardoni, with whom he would become associated in 1880 under the name Gilardoni & Brault. Two years later, Alfred Brault, son of Alphonse, took over the reins of the company. After the death of Alphonse Brault in 1895, the company became Gilardoni fils A. Brault et Cie. When Alfred Brault retired in 1902, the company then became Gilardoni fils et Cie and remained flourishing until the beginning of the decade. For more information, please consult the site céramiquearchitecturale.fr

[4] Guimard’s first contacts with the Manufacture may date back to this exhibition and will lead to the publication of three works of art.

[5] This series of postcards summarising Guimard’s modern work was published on the occasion of the Housing Exhibition at the Grand Palais in 1903.

[6] The 1903 postcard mentions “Porche en Céramique d’une Habitation” (Ceramic porch of a Dwelling) and Guimard’s graphics preserved in the Musée d’Orsay “Porche d’une gde habitation parisienne” (Ceramic porch of a large Parisian dwelling) (Guimard collection, GP 1840-1841-1846).

[7] The meeting with Guimard probably dates from this period and their collaboration will end a few months later with the edition of a vase.

[8] Thiébaut, Philippe, Guimard, catalogue of the exhibition presented at the Musée d’Orsay in 1992, p. 259.

[9] Vigne, Georges, Hector Guimard, Editions Charles Moreau, 2003, p. 111.

[10] Library of the Arts Décoratifs, ref. T 95/A.

[11] Xavier Raphanel (1876-1957), a pupil of Falguière, is the author of numerous historicist statuettes and some decorative art objects.

[12] Jean-Désiré Ringel dit Ringel d’Illzach (1849-1916), of Alsatian origin, also a pupil of Falguière, had his studio in rue Chardon-Lagache, in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, close to the Guimard action zone.

[13] Op .cit.

[14] The term “porcelain stoneware” which was then used by the Manufacture de Sèvres must be understood as a synonym for glazed stoneware.