Category: News

The Hôtel Mezzara will become the Guimard Museum !

29 June2025

After more than twenty years of commitment, Le Cercle Guimard is seeing its project become a reality: the Hôtel Mezzara will soon be home to the Guimard Museum, dedicated to one of the masters of Art Nouveau. Twenty-two years after the creation of the Cercle Guimard, and nineteen years after our first exhibition at the Hôtel Mezzara (“Guimard, album d’un collectionneur”), our association is now taking a decisive step towards the creation of the Guimard Museum. We are proud to announce that our team — Le Cercle Guimard, Hector Guimard Diffusion — with co-financers FABELSI and Banque des Territoires (Groupe Caisse des Dépôts) — has won the call for applications for a fifty-year lease on the Hôtel Mezzara, Hector Guimard’s masterpiece and a listed historic monument. The official letter was sent to us on June 23, 2025.

Hall of Hôtel Mezzara- current state. Photo F. D.

Since this State-owned property was declared “of no public interest” ten years ago, our association has devoted all its energy and resources to turning the Mezzara Hotel into the future Guimard Museum. The strategic turning point in our campaign came in 2017 with the organization of the exhibition “Hector Guimard, précurseur du design” (Hector Guimard, pioneer of design), intended to demonstrate the potential of the Mezzara Hotel as a museum setting. The media coverage generated by the exhibition brought our project to the attention of the public.

Thanks to Belgian architect and historian Maurice Culot, in 2018 we met Fabien Choné, an entrepreneur with a passion for heritage, who breathed new life into our initiative. With his organization “Hector Guimard Diffusion”, we became co-sponsors of the private museum project, which we have since structured and developed together. Two calls for tenders launched by the French State, were declared unsuccessful, before our application was finally accepted on the third attempt.

All these years have enabled Le Cercle Guimard to become more professional, build up a collection, create an archive center and a publishing house — Les Éditions du Cercle Guimard, whose first publication was devoted to the Hôtel Mezzara — to continue our reissue and digitization projects, to develop research on Hector Guimard and his creations, and to establish the association’s headquarters in the architect’s former agency, at Castel Béranger.

An exciting period is now beginning: alongside Art Nouveau specialists, craftsmen, restorers, architects, and cultural and institutional partners, we will design a museum worthy of one of the greatest architects of the turn of the 20th century.

Loggia of the Hotel Mezzara on the second floor on the front of the street side, external view Photo F. D.

First and foremost, we would like to warmly thank our members and the members of the board of directors for their loyalty, commitment, and patience throughout these years of hard work.

We are grateful to Jean-Pierre Lyonnet, the first president of the Cercle Guimard, who passed away several years ago, as well as to all the former members of the board who actively contributed to the development of the association.

Thank you, Arnaud, thank you, Bruno.

We also have fond memories of the first “hectorologists,” some of whom are still members of the Cercle: Henri Poupée, Roger-Henri Guerrand, Alain Blondel, Michèle Blondel, Yves Plantin, Laurent Sully Jaulmes, and Ralph Culpepper.

We are of course also very grateful to Philippe Thiébaut, honorary curator of heritage, and Georges Vigne, curator of heritage, who have significantly advanced knowledge about Hector Guimard through their research, exhibitions, and publications.

And we would also like to thank:

The DRFIP, the State Property Department, the local Paris property department, the Ministry of Culture, the DRAC Île-de-France, and the members of the application review committee for the trust they have placed in us.

The RATP for its active support in promoting Guimard’s legacy.

The museums and institutions that support us and have announced exciting collaborations:

The Musée d’Orsay

The Musée des Arts Décoratifs (MAD Paris)

The Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine

The Le Corbusier Foundation

The Archives de Paris

The Musée de l’École de Nancy.

The City of Paris, and in particular Karen Taïeb, Deputy Mayor of Paris, whose constant and decisive support was essential, notably in initiating the Guimard Year in 2023, which greatly contributed to raising awareness of our project.

The Municipality of the 16th arrondissement for its commitment to the museum, and in particular:

Jérémie Redler, mayor of the 16th arrondissement

Samia Badat-Karam, first deputy mayor

Bérengère Gréé, Paris city councilor.

The department of Haute-Marne and the town of Saint-Dizier for their support for Guimard’s artistic castings, with the assistance of:

The GHM foundry

The municipal museum of Saint-Dizier and its curator Clément Michon

Élisabeth Robert-Dehault and all the local stakeholders involved.

Normandy and the town of Cabourg, where Guimard built three iconic villas (La Sapinière, La Bluette, La Surprise),

with the support of:

The Villa du Temps Retrouvé

Tristan Duval, Emmanuel Porcq, Roma Lambert.

Our American partners, who have contributed greatly to Guimard’s international recognition:

The Driehaus Museum

The Art Institute of Chicago

The Alliance Française of Chicago

The Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York

The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Delta Air Lines.

We would also like to express our sincere thanks to Barry Bergdoll, David Hanks, Sarah Coffin, Ingrid Gournay, David Dozier, and Elisabeth Cummings.

In Catalonia, we would like to thank Teresa Sala, Professor of Art History at the University of Barcelona and specialist in Catalan Modernism.

In Belgium, we would like to thank the Horta Museum and its curator Benjamin Zurstrassen, as well as Françoise Aubry. Our project also aims to strengthen ties between Brussels and Paris around Art Nouveau.

Loggia of the Hotel Mezzara on the second floor on the front of the street side, internal view Photo O. P.

We would also like to thank the professionals who contributed to the quality and strength of our application:

Rydge Avocats, for their legal support

KPMG, for their financial and tax expertise

Beaux-Arts Consulting, for their strategic and cultural expertise

Thibierge Notaires, for the notarial aspects

REVA (Bruno Donzet and Maurice Masri), for the project’s economics

Picard Expertise, for the real estate appraisal

Dozier Stratégie, partnership and cultural financing consultants

We express our deep gratitude to all those who, in one way or another, have supported this project: elected officials, researchers, museums, institutions, associations, journalists, collectors, and enthusiasts—in France and abroad. We would also like to thank all those who, even briefly, crossed our path and offered their help or advice at the right moment. These ten years of effort have enabled us to forge many strong bonds, often friendships, that we will never forget.

The Cercle Guimard executive committee

Nicolas Buisson, Frédéric Descouturelle, Nicolas Horiot, Peggy Laden, Dominique Magdelaine, Olivier Pons

What color were the red signaling glasses on Guimard’s metro surrounds?

( Note: in this article, the term “signaling glass” is used to translate the French “verrine”, meaning the protective cover of the lamp in a Guimard Metro candelabra)

Due to the flow of contradictory information, we are being urged from all sides to give our opinion on this crucial point. We are happy to oblige, all the more so as we had neglected to add any nuances to the overly clear-cut opinion, we expressed in the two books published in 2003 and 2012 that established a serious study of Guimard’s metro [1]. The recent discovery of a color photograph taken in the 1960s is a fitting conclusion to our article.

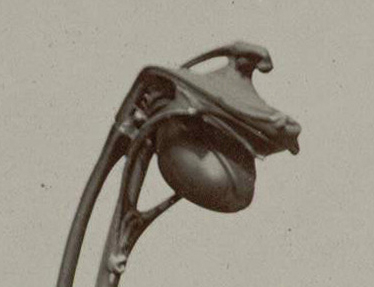

To define the curved glass pieces that complete the candelabras on the open surrounds of Guimard’s Paris metro entrances, we have adopted the term used at the time by the CMP (Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris), “signaling glass”, rather than “globe”, which refers to an image of a sphere [2]. Due to the low luminosity of their electric bulb, which is entirely covered by the signaling glass, the function of these lights is nocturnal signaling rather than lighting. This latter function, which Guimard had not foreseen, as it had not been requested [3], was gradually taken over by uncovered lamps installed by CMP on the aediculae and on certain open surrounds. The surrounds of the additional entrances [4], which at the time were used solely for exiting, had neither luminous signage nor lighting.

Originally, these signaling glasses were indeed made of glass. For a more complete study, we refer the reader to our dossier Hector Guimard, Le Verre pp. 20-23, published in pdf format in 2009 and still accessible on our website. We give some extracts below.

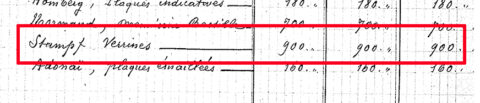

We know the supplier of these signaling glasses thanks to a few rare archives. The first is a CMP accounting document, dated September 12, 1901, listing the names of the various suppliers and the costs incurred with each of them for Guimard’s first project, i.e. the construction of surface accesses for line 1 and two additional sections of future lines 2 and 6. Entitled “Travaux des édicules/M. Guimard Architecte”, this document actually lists the costs incurred for both the aediculae and the uncovered surrounds. The penultimate line of the document reads: “Stumpf, Signaling glass […] 900”.

Detail of a breakdown of surface access expenses for the first Paris metro project. RATP document.

This company, better known as “Cristallerie de Pantin”, had been called Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet et Cie since 1888. It was founded in La Villette in 1851 by E. S. Monot, then transferred to Pantin in 1855. It rapidly prospered, becoming France’s third-largest crystal works (after Baccarat and Clichy) after the 1870 war (and the transfer of the Saint-Louis crystal works to German territory). In 1919, it was absorbed by the Legras glassworks (Saint-Denis and Pantin Quatre-Chemins).

The price of 900 F-gold corresponds to 30 signaling glass at 30 F-gold each, i.e. 13 pairs of signaling glass for the 13 uncovered surrounds of the first project, plus 4 additional pieces in case of breakage. This price per unit is confirmed by another undated CMP accounting document for line 2, which sets the price of two signaling glass for each frame on the section from Villiers to Ménilmontant stations at 60 gold Francs. It was clearly stated that this price was identical to that set for the surrounds on the first site. The Cristallerie de Pantin’s commitment to Guimard and the CMP to maintain the price of glassware for Line 2 surrounds is also the subject of three documents (one handwritten and two typewritten) from November 1901 to January 1903.

There were 103 Guimard surrounds on the network, and twice as many signaling glass on their lampposts. They were still in place in 1960, when Louis Malle filmed ” Zazie dans le métro”, based on the novel by Raymond Queneau.

Catherine Demongeot for Zazie dans le Métro in 1960, promotional photo or set photo for a scene not included in the film. The signaling glass shows the characteristic glass stopper at the tip. Private collection.

Early loans (later transformed into donations) of Guimard surrounds, complete or otherwise, enabled the preservation of their glass cases. Thus, the portico of the uncovered surround at Raspail station, installed in 1906, entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1958. The same is true of the surround for Bolivar station, installed in 1911, which entered the collections of the Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Munich in 1960 (not on display).

Portico from the uncovered surround of the Raspail station at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The portico includes red glass signaling glass. All rights reserved.

In 1961, the Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris also received a complete surround, one of two from the Montparnasse station (installed in 1910). Returned to the Musée d’Orsay, it can be viewed on the occasion of thematic exhibitions.

Portico of an open surround from the Musée d’Orsay, loaned (then donated) by the RATP in 1961 to the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, from the Montparnasse station (1910), with the exception of the enameled lava sign (before 1903). The signaling glasses are indeed glass. Photo D. Magdelaine.

Shortly afterwards, in 1966, the RATP donated a complete Guimard surround (without sign holder) to the Montreal metro company. The seven-module long, five-module wide entourage was composed from elements taken from the reserves and resulting from the dismantling of certain entrances. It included two glass signaling glass

The Guimard open surround for Montreal’s Victoria metro station, in storage prior to shipment in 1966. Photo RATP.

So it was only later, at a date that is still difficult to pin down, that RATP replaced the glass signaling glass with red synthetic equivalents, which were cheaper, less fragile, but far less beautiful. However, as a symptom of RATP’s long lack of interest in this period of its history, the signaling glass that had been salvaged from these exchanges mysteriously disappeared from its reserves, so that by the end of the twentieth century it no longer possessed a single one.

As luck would have it, during restoration work on the entrance to Montreal’s Victoria station, the STP metro company had the wisdom to replace its somewhat damaged glass signaling glass and give one back to the RATP in 2003 [5]. This was the first signaling glass we had the opportunity to examine up close, admiring its clean lines, satin-finish surface and color, which varies from dark red to light orange, depending on the lighting and the thickness of the glass.

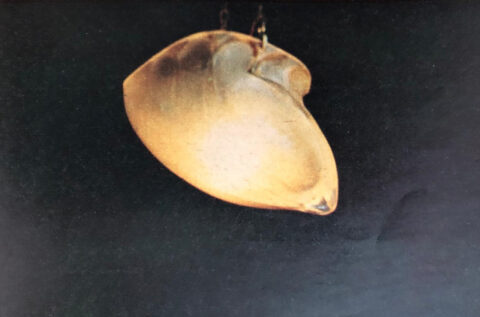

Glass signaling glass of an uncovered Guimard surround, from the uncovered surround offered to Montreal in 1966 and donated to the RATP in 2003. Photo F. D.

We have also learned of the existence of a signaling glass [6], also red, on a copy of a Guimard bronze surround in the USA. This unexpected presence, attested to by a State report [7] drawn up in 2002, confirms the existence of a network for the fraudulent export of Guimard metro parts to the USA.

Copy of a bronze surround placed around a pond in Houston in the 2000s. Photo Artcurial.

For the supply of special glass for the windows and roofs of kiosks and pavilions, we have a contract between CMP (Compagnie du Métro Parisien) , Compagnie de Saint-Gobain and glassmaker Charles Champigneulle. This contract clearly specifies the color of the glass prescribed. However, we have no record of an initial contract for the supply of the signaling glass, which would undoubtedly have enabled us to know the color originally envisaged by Guimard. Given the color of the known glass signaling glass, all orange-red, we logically assumed that they all were. This opinion was supported by the fact that on some old black-and-white shots, considering the reflection of light, the signaling glass appears to be dark, which is compatible with a red color.

Uncovered surround of the Rome station, installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

However, this opinion has been challenged by several facts.

The first, to which we should have paid more attention, is the autochrome photograph (giving the actual colors) of Porte d’Auteuil station, dated May 1, 1920 and held in the collection of the Musée Départemental Albert-Kahn. We were unable to reproduce this photograph in the book Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro due to the museum’s opposition to its publication. Since then, having been included in an exhibition, it has been re-photographed by visitors and is now accessible to all thanks to Wikipedia.

.

Surround of the Porte d’Auteuil station. Photo Heinrich Stürzl, based on an autochrome plate by Frédéric Gadmer, taken May 1, 1920. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn collection (inv. A 21 126). Source Wikimedia Commons.

This picture clearly shows that the signaling glasses are white, not red. To the best of our knowledge, we have no other autochrome images of the period. In our opinion, colorized postcards such as those in the “Le Style Guimard” series, published in 1903 on Hector Guimard’s initiative, cannot serve as a reliable reference, since the process consists in softening the contrast of a black-and-white shot and superimposing transparent flat tints of color which, while often plausible, are sometimes different from reality.

Antique postcard “Le Style Guimard” published in 1903. Private collection.

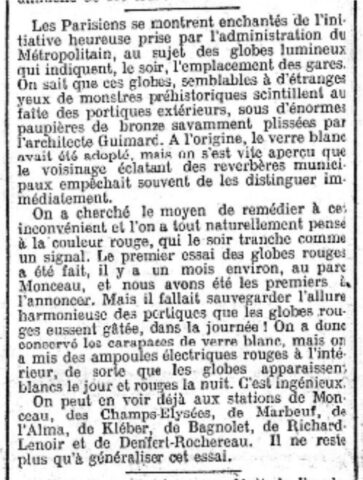

Secondly, the existence of an article published in 1907 in the conservative daily Le Gaulois definitively calls into question the certainty of the exclusive red color of the signaling glasses. We missed this newspaper article in 2003 and 2012. We owe its discovery to an author we will not name.

Unnamed author : echoes from everywhere Le Gaulois September 18, 1907.

This article begins by explaining why red was preferred to white: more effective night-time signage. It also seems to settle the question of the change of color by establishing that in August 1907, CMP carried out a trial of red signaling glasses on the open surround of Monceau station (line 2), and that a month later, in September 1907, seven more stations were fitted with them. At the same time, on other Guimard surrounds, the CMP had obtained a red color by placing red bulbs in the white glasses. It should be noted in passing that the author justifies this temporary measure by “[safeguarding] the harmonious allure of the porticos, which the red globes would have spoiled during the day”. This justification is all the more strange given that red, acting as a complementary color to the green of the fonts, is more pleasing to the eye than white. Did the journalist copy a “piece of language” communicated by the CMP?

By 1907, red signaling glasses were destined to gradually replace white ones. And yet, it is highly likely that the surrounds of Rome station, photographed with certainty in 1903, already featured red glasses, as can be seen in this enlargement of Charles Maindron’s photograph (see above).

Open surround of the Rome station (detail), installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

On the contrary, the autochrome plate of the Porte d’Auteuil surround (see above) shows white signaling glasses. In this case, however, it was one of the very last Guimard surrounds to be installed by the CMP, on line 10 in 1913 [8]. Logically, therefore, it should have been fitted with red glasses. But at a time when there was no doubt talk of definitively abandoning the use of Guimard entrances, it is likely that white signaling glasses from earlier replacements were used.

To conclude this little study, we finally had the opportunity to discover the image of a white signaling glass thanks to the photographic collection bequeathed to The Cercle Guimard by our friend Laurent Sully Jaulmes. It is just a detail from a very surprising shot taken in Germany in 1967, which we’ll come back to one day. On this occasion, the signaling glass was used as a chandelier.

White signaling glass used as a chandelier. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes (detail), 1967. Cercle Guimard archives and documentation center.

So we don’t despair of seeing signaling glass arrive on the art market in the next few years, because we can’t believe that almost all of those that were originally set up have subsequently been destroyed. On the contrary, a sufficient number of them must still be in private storage. As new generations arrive, they will inevitably reappear, allowing us to take a closer look at these magnificent glass vessels, whether red or white.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Le Métropolitain de Guimard, éditions Somogy, 2003; Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro, éditions de La Vie du Rail, 2012. [2] One of the earliest designs for a surround with a rounded base, project no. 2, was not validated by the authorities, and featured globular-shaped signaling glasses clamped in a cast-iron jaw, see our article Un porte-enseigne défaillant sur les entourages découverts du métro. [3] The 1899 competition (in which Guimard did not take part) stipulated the presence of a signpost for open surrounds, without mentioning a light source. However, most candidates included one in their proposals. [4] Low cartouche surrounds installed on the network from 1903-1904. [5] The other signaling glass was entrusted to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. [6] One of the signaling glasses was then stored and replaced by an equivalent in synthetic material. [7] This condition report, carried out at the home of the owner of the surround copy in Houston, was written on June 27, 2002 and signed by Steven L. Pine, decorative arts conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and a specialist in metal conservation. It refers to a previous report of June l6, 1999. [8] It also shared with the Chardon-Lagache station a peculiarity in the way the crests were hung, a sign, perhaps, of a change in the assembly teams.

The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 1 June 11, 2025

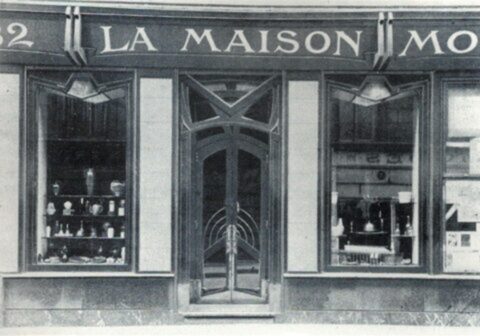

Thanks to our Swiss member Michel Philippe Dietschy-Kirchner, we got in touch with Bertrand Mothes, author of a study on “La Maison Moderne”, founded in Paris by German art critic Julius Meier-Graefe. Often overlooked in favor of its better-known competitor, Siegfried Bing’s La Galerie de l’Art Nouveau, it nevertheless published leading decorative artists such as Maurice Dufrène. Its links with Guimard are tenuous and indirect, but not non-existent. Bertrand Mothes has given us the honor of sharing a summary of his work with us.

The last decade of the 19th century was a period of radical change in the field of decorative arts in Europe. Artists, patrons, critics, and institutions actively participated in this renaissance of applied arts, each according to their own methods and ideas, but always with the aim of breaking away from the historicist pastiche in which decorative artists and architects had become trapped during the second half of the century. In this climate of emulation, the role of dealers should not be overlooked. In 1895, Siegfried Bing opened the Galeries de l’Art Nouveau at 22 Rue de Provence in Paris. While this gallery is now the best known and the one with the richest historiography, it is important to consider the environment of Parisian art galleries of the period, an environment that included “La Maison Moderne”. This establishment, founded by German art critic and historian Julius Meier-Graefe in 1899, stood alongside Bing’s Art Nouveau as the second center for the trade in innovative decorative arts in the French capital at the turn of the century. Like the Galerie de L’Art Nouveau, La Maison Moderne was a shop where Parisians could come to furnish their homes and buy works of art, trinkets, and fashion accessories. However, its structure and operation differed from those of 22 rue de Provence and reflected the mindset of its owner. Similarly, the selection of artists- some of whom worked for both stores—reflected Julius Meier-Graefe’s aesthetic choices.

The soul of « La Maison Moderne”

The first element to examine to understand the origins of La Maison Moderne is the definition of the goals of its creator, Julius Meier-Graefe. Indeed, the gallery was modeled according to his wishes, and he embodied its spirit throughout its entire period of activity. The son of Edward Meier, one of the leaders of the steel industry in Germany, and Marie Graefe, who died giving birth to him [2], Julius Meier-Graefe was born on June 10, 1867, in Reșița [3]. His family moved to the Rhineland and the young Julius grew up near Düsseldorf. He obtained his Abitur in 1879 and began studying industrial engineering with a view to taking over his father’s business [4], first in Munich in 1888 and then the following year in Zurich and Liège. He already seemed attracted to the world of art: he visited the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris and left for Berlin in 1890. He then began studying art history under Herman Grimm and left Berlin without graduating [5].

Edvard Munch, portrait of Julius Meier-Graefe, 1894. Iil on canvas hight. 100 cm, width 75 cm, collection: Nasjonalmuseet for kunst, arkitektur og design, Oslo, photo : Høstland, Børre, Creative Commons – Attribution CC-BY.

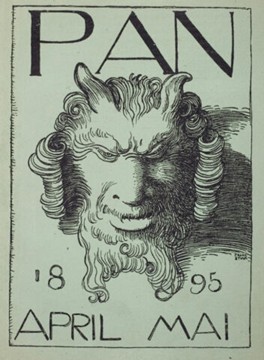

The year 1893 saw Meier-Graefe’s first involvement in the arts: he helped his friend Edvard Munch organize an exhibition and published his first work, the novel Nach Norden (“Towards the North”). That same year, he traveled to England, where he met the most important representatives of the Aesthetic Movement and Arts and Crafts, including Oscar Wilde, William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones, and Aubrey Beardsley [6]. In 1894, he helped found the Pan association and became editor of the eponymous magazine that accompanied it. He shared the title of editor-in-chief with the writer Otto Julius Bierbaum. Meier-Graefe was responsible for editing articles related to the fine arts, while Bierbaum took care of those devoted to literature [7].

Franz von Stuck, Cover of the magazine Pan, April-May 1895. Coll. Université de Heidelberg. All rights reserved.

He then began writing about decorative arts. In his view, painting had lost touch with society, and it was necessary to turn to the applied arts to revive art [8]. Meier-Graefe thus wanted to add an art salon to the Pan association. He wanted to make this salon a new kind of venue, breaking with the exhibitions organized at the time, which no longer satisfied the public, and proposed bringing together all the arts in coherent interiors, without distinction between fine arts and applied arts. His goal was to bring artists and spectators together and create a “modern and harmonious” environment [9]. This idea of an art salon seems to have emerged in his mind after his trip with Siegfried Bing to Belgium in the spring of 1895. They visited the Maison d’Art de la Toison d’Or in Brussels. This gallery, founded in 1894 by the Société Anonyme l’Art, was located in Edmond Picard’s mansion at 56 avenue de la Toison d’Or and was run by his son William Picard. The aim of the Société Anonyme l’Art, which was to stimulate the production of applied arts, was reflected in the presentation method chosen, which was completely new at the time: the layout of the mansion was preserved and the objects—contemporary works of art and craftsmanship intended for everyday use—were displayed in the rooms. This approach differed from the usual arrangement in galleries at the time, which consisted of simply displaying the objects for sale on shelves in soulless, undecorated spaces. Bing and Meier-Graefe were impressed by its innovative approach [10]. Immediately after their visit to the Maison d’Art, Meier-Graefe and Bing also visited Henry Van de Velde, who had just begun construction of his new house, the Bloemenwerf, in Uccle. In his memoirs, Van de Velde recalls “a trip that was intended to inform them about the revival of the arts and crafts in England and various countries on the continent. From Brussels, they were to travel to England, then return via Holland to Denmark, Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia (11).”

View of the Bloemenwerf, house of Henry Van de Velde, built in 1895 at Uccle in the suburbs of Brussels. All rights reserved.

Van de Velde goes on to explain Meier-Graefe’s intentions and proposals, which include expanding his network of contacts and finding new topics for articles to contribute to the development of art magazines in Germany. Meier-Graefe therefore suggests to Van de Velde that he join the foreign contributors to the magazine Pan. The two travelers are apparently convinced of the need to work with Van de Velde and are full of praise for his taste in interior design [12]. Upon departure, Bing expressed his desire to reconnect with Van de Velde with a view to a possible collaboration when he returned to Paris. It was at the end of this trip that Meier-Graefe encouraged Bing to transform his Parisian gallery, inspired by the edifying example of the Maison d’Art as an innovative gallery.

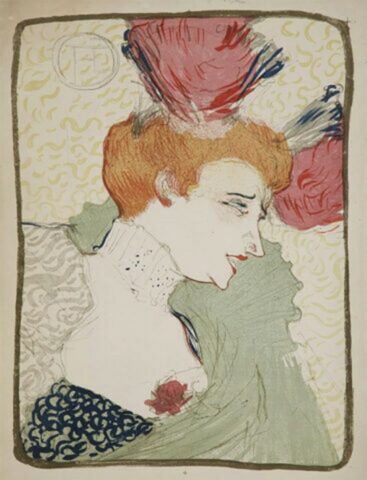

At the end of the year, Meier-Graefe left the Pan association following a disagreement over the publication, in the September-November 1895 issue of the magazine, of a lithograph by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mademoiselle Lender, in bust, which was deemed immoral by some members of the editorial board [13].

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Mademoiselle Marcelle Lender en buste, 1895, color lithography on paper, Vente Tajan, Paris, 3 May 2022, lot 43. All rights reserved.

He then moved to Paris in the following months, while continuing to contribute to German magazines. From that point on, Meier-Graefe wrote little about painting and focused on the decorative arts. In parallel with his writing, at the end of 1895 he became artistic advisor to Siegfried Bing at his Art Nouveau gallery, where he organized exhibitions [14].

The gallery of L’Art nouveau Bing, at the angle of rue Chauchat and rue de Provence, rehabilitation by the architect Louis Bonnier in 1895. Photo Édouard Pourchet. All rights reserved.

Meier-Graefe’s role within Bing’s company placed him at the center of a network of artists, enriching the one already established in Germany. However, his actions were not without criticism from leading figures in the French art scene, such as Auguste Rodin, Octave Mirbeau, and Edmond de Goncourt, who accused him of seeking to overturn “good taste” and the tradition of French decorative arts. Meier-Graefe and Art Nouveau were nevertheless defended by eminent critics such as Camille Mauclair, Gustave Geffroy, Thadée Nathanson, and Roger Marx [15]. After six months of collaboration, Meier-Graefe left Bing’s gallery. The two men continued to see each other, however.

Julius Meier-Graefe then returned to writing. In an article published in Das Atelier in 1896, he described what he considered outdated in the field of interior design. For him, Edmond de Goncourt’s house, furnished in the 18th-century style, no longer met the needs of a late 19th-century interior:

“A modern person cannot live in Second Empire “bric-a-brac”. Taking something from another era and placing it in a new environment can be as disastrous as the barbaric imitations of old models in the decorative arts.

Meier-Graefe also criticized the “museum-like” aspect of this residence during the auction of its contents in 1897. This idea of anachronism concerning the interior decor and furnishings was a constant theme for Meier-Graefe, who used it as an argument in favor of modernity. He considered that “living in a salon in the purest Regency style is equivalent, for a citizen of the Third Republic, to donning a hammered wig and a ribboned coat” and that a collector furnishing his interior in an antique style “often makes himself look as ridiculous as the Bourgeois Gentilhomme [18].”

Another article by Meier-Graefe, published in June 1896, serves as a profession of faith and an affirmation of his commitment to supporting modern decorative arts [19]. In it, he develops his view that divides art into “external environment” and “internal environment.” According to him, the 19th century was the century of the “external environment” dedicated to realistic art, and his era reacted to this artistic conception with “fantastic” art—a term understood today as ‘symbolist’—which aimed to be “useful.” He placed the applied arts at the center of this artistic renewal and believed that modernity could win over the public through the “neutral” field of decorative arts. He was one of the persons best placed to support this development of decorative art, given his interest in it, but also thanks to his knowledge in this field and his network of contacts throughout Europe. He shared this point of view with many artists who were beginning to abandon painting and sculpture to devote themselves to “useful” art, Henry Van de Velde foremost among them.

Meier-Graefe continued to write and, in 1897, acquired the best tool available for conveying his ideas: a magazine of which he would become editor, Dekorative Kunst. This German-language magazine was co-founded and published by Hugo Bruckmann from Munich. Most of the articles were written by Meier-Graefe himself, who used a large number of different pseudonyms [20]. Modelled on the English magazine The Studio, the journal was international in its approach, being published in Germany but with offices in Paris. Its aim was also to transcend borders, as indicated in the launch brochure. Meier-Graefe explained that abstract art had become an end in itself and was now only appealing to a minority of enthusiasts, while interior design and home décor had been abandoned to unscrupulous manufacturers who were content to produce poor replicas of old styles. A reaction against this state of affairs was said to be underway, and the new magazine, devoted exclusively to modern decorative art, would participate in this renewal by preparing the ground. This focus on modern applied arts alone sets it apart from other magazines created or revamped at the same time, which were devoted to both modern and ancient art, such as the Revue des Arts Décoratifs and Art et Décoration in France, The Studio in England, and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration in Germany.

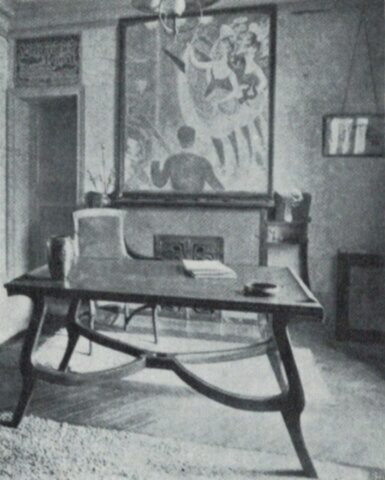

Meier-Graefe did not just write about decorative arts, he also put his ideas into practice in his new magazine with the help of Belgian artists: the title page of the first issue of Dekorative Kunst was designed by Henry Van de Velde and Théo Van Rysselberghe [21]. Meier-Graefe called on a third Belgian artist, Georges Lemmen, to design two posters and some letterhead for other promotional materials for his magazine. Meier-Graefe took his idea even further, commissioning Van de Velde to design the magazine’s editorial offices at 37 Rue Pergolèse in the 16th arrondissement [22].

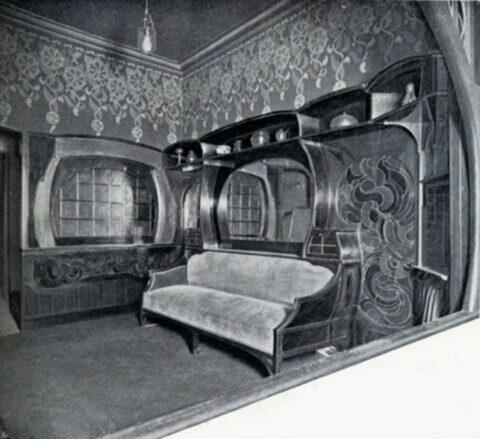

Editorial office of the magazine Dekorative Kunst in Paris, 37 rue Pergolèse, reproduced in Henry Van de Velde, Sembach, Klaus-Jürgen, ed. Hazan, 1989. Above the door is a poster by Georges Lemmen with the title of the magazine, and above the fireplace is Seurat’s Le Chahut (now in the Musée d’Orsay). All rights reserved.

It seems that Meier-Graefe was already behind the collaboration between the Belgian decorator and Siegfried Bing in 1895[23]. Following the negative reactions to his interior designs at L’Art Nouveau—Rodin called Van de Velde “a barbarian” [24]—Van de Velde seemed to have lost his appreciation for Paris [25], but Meier-Graefe, convinced of his potential success in France, did everything he could to get him recognized there.

Salon designed by Henry Van de Velde for the opening of the Bing Art Nouveau Gallery in 1895. Photograph reproduced in Gabriel P. Weisberg, Les Origines de l’Art Nouveau, la maison Bing, published by the Musée des Arts décoratifs, 2004. All rights reserved.

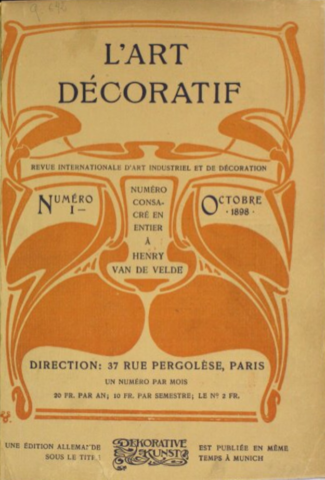

In view of the success of Dekorative Kunst, and in order to spread his ideas even more widely, Meier-Graefe founded the magazine L’Art décoratif, the French counterpart to the original publication. The first issue was published in October 1898 [26]. It was entirely dedicated to Henry Van de Velde, whom Meier-Graefe commissioned to design the cover [27] and redesign the magazine’s offices.

Henry Van de Velde, cover of the first issue of the magazine L’Art Décoratif, October 1898. Library of the National Institute of Art History, Jacques Doucet collections. All rights reserved.

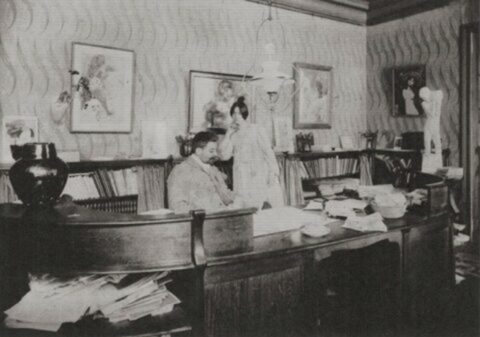

Julius Meier-Graefe and his wife in his office at the editorial office of the magazine L’Art Décoratif, 37 rue Pergolèse in Paris, circa 1898-1899. On the wall to the right, Madonna by Edvard Munch. Photo Royal Library of Belgium, Archives and Museum of Literature, reproduced in Henry Van de Velde Passion Fonction Beauté, published on the occasion of the exhibition of the same name at the Cinquantenaire Museum in Brussels, 2013, Lanoo, Tielt, 2013. All rights reserved.

The subtitle of L’Art décoratif, Revue internationale d’art industriel et de décoration, sums up the battle that Meier-Graefe had undertaken the previous year in the German-speaking world and which he now wished to wage in the French-speaking world. His approach was outlined in the preface to the first issue. He wanted to find a rational way of organizing the production and distribution of modern art objects. He wanted to break with the French tradition of promoting “rare objects.” He deplored the situation in the art industries at the time, which forced decorative artists to respond only to commissions from wealthy collectors and did not encourage industrialists with the necessary infrastructure to manufacture objects in large quantities to call on artists to design their models, producing only objects that copied old styles. Meier-Graefe wanted to change this state of affairs and hoped to reconcile artists with industry, which alone can make beauty accessible to the masses. From the third issue of L’Art décoratif, his desire to contribute to the art trade was clear: a fan by Georges de Feure, produced in a limited edition of 100, was offered to readers of the magazine, who had to contact the editorial office to order the item. This was Meier-Graefe’s first venture as an art dealer.

The need for a new gallery

A radical change was afoot in Meier-Graefe’s work. Although he left Bing’s Art Nouveau to concentrate on his writing, he continued to regard it as the ideal structure for promoting the modern style in Paris. However, during the last years of the century, he began to change the decorative concept he wanted to promote at L’Art Nouveau. Barely a year after the gallery opened, profits were already falling short of expectations, as Paul Signac pointed out: “Business is not going well at all; he doesn’t know what he wants, nor what customers want. He is in dire straits and I think he will soon move on to other pursuits[ 31].” Bing therefore began to favor artists with a more “French” conception of decorative arts [32]. This ‘return’ to the “French tradition” of furniture culminated at the 1900 World’s Fair, where Bing’s pavilion presented works by Georges de Feure, Édouard Colonna, and Eugène Gaillard.

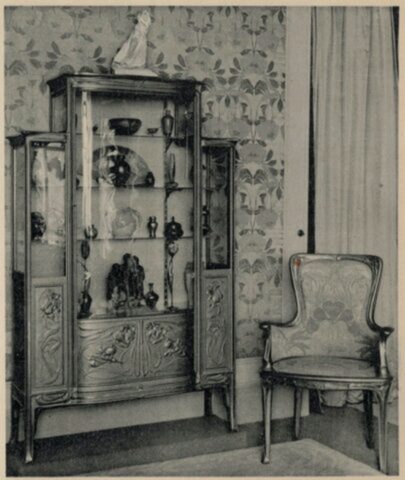

Gilded wood display cabinet and armchair by Georges de Feure in the Bing Pavilion at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. Portfolio Modern-style furniture 1900 World’s Fair. Private collection.

Meier-Graefe, for his part, “will not allow any kind of compromise, at least for the moment [33].” He was already aware of the economic and financial stakes involved in a business such as L’Art Nouveau. The companies run by Louis Majorelle and Gustave Serrurier-Bovy were models of thriving businesses with processes that differed from those of Bing. Even though he set up his own workshop to create luxury items for his gallery, Meier-Graefe considered that he had “underestimated the enormous growth of this market for new products” and that he had not taken into account the competitive environment specific to Parisian furniture galleries[34].

These various factors led Meier-Graefe to consider setting up his own private art gallery, which he would run and where he would exhibit only works by artists who shared his vision of modern decorative art. By 1899, Meier-Graefe had given the matter a great deal of thought and his ideas had matured. The project was launched later that year. Drawing on his “instinctive feelings and knowledge,” Meier-Graefe began to assemble a “team” of artists who would select the works to be sold in his gallery and decide how and by whom it would be designed. From that date on, he gradually gave up the editorial direction of Dekorative Kunst and L’Art décoratif to devote himself entirely to his project [36]. He was also able to start his business thanks to a large inheritance from his father, who died in 1899. However, the lack of archives does not allow us to know whether Meier-Graefe received any financial support other than his inheritance and personal investment when he set up his gallery [37]. His change of activity and his increasing involvement were praised in the preface to Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), published in 1901 by La Maison Moderne:

“Ten years ago, it was his pleasure to support, in magazines, with passionate enthusiasm, the doctrine of the equality of the arts […]; but Mr. Meier-Graefe was not content with the contemplative and usually ineffective action devolved to the critic; he wanted to prove his words, to move from theory to practice, from propaganda to fact. [38]“

Front of La Maison Moderne, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, 1900, reproduced in Henry van de Velde, Ein europäischer Kunstler seiner Zeit, Sembach/Schulte, catalog of the eponymous exhibitions 1992-1993, ed. Weinand-Verlag, Cologne, 1992. All rights reserved.

The opening of the gallery was reported in the magazines of which he was still editor. The September 1899 issue of L’Art décoratif featured a page written by Meier-Graefe himself (under a pseudonym) announcing the upcoming opening of La Maison Moderne, “a new house for the production and sale of everyday art objects.” The following issue specified the date of the opening, scheduled for the second half of October, and announced that a preview would be held to which subscribers to the magazine would be invited[40]. However, the opening to the public was postponed, as reported in the November 1899 issue, “due to renovation work that the contractors had not anticipated[41].” This is the last mention of the gallery’s imminent opening. A letter sent by Van de Velde to his wife Maria, dated November 15, 1899, and mentioning the opening of the gallery, allows us to estimate more precisely the date of this event, which must have taken place between November 1 and 15, 1899. Van de Velde explains that the opening of La Maison Moderne was not as famous a social event as that of L’Art Nouveau four years earlier, but he was not concerned: “This opening is not sensational, far from it, but nevertheless I believe in the success of the venture[42].” Despite the lack of enthusiasm generated by the creation of a new gallery, Meier-Graefe and his collaborators were convinced of their innovative potential and the future success of their venture.

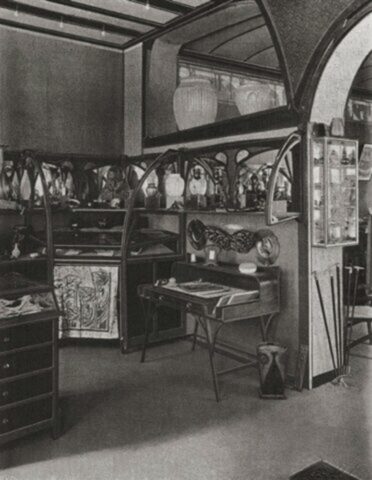

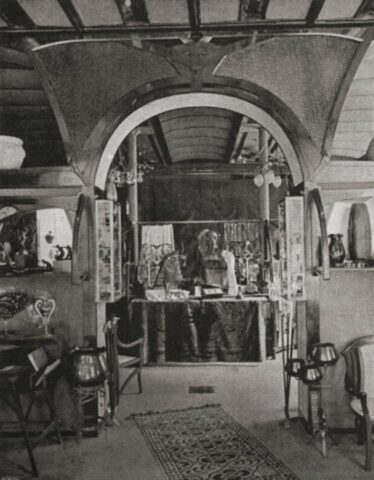

Interior design of La Maison Moderne in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, 1900, reproduced in Henry Van de Velde Passion Function Beauty, published on the occasion of the eponymous exhibition at the Musée du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, 2013, Lanoo, Tielt, 2013. All rights reserved.

La Maison Moderne was, for its creator, an unprecedented venture: opposed to trade shows and official exhibitions due to the multiplicity of objects on display and their presence in multiple copies, but also opposed to department stores thanks to the indisputable artistic quality of the objects offered for sale, it was also different from workshops’ own shops, such as those of the Daum brothers or Louis Majorelle. La Maison Moderne was similar in style to Bing’s gallery, but Meier-Graefe believed that there was a significant difference between the two, beyond mere stylistic differences. Unlike Bing, who chose to appeal to a very wealthy clientele, Meier-Graefe wanted to include his establishment in “a new category of ‘modern art galleries’ that would meet the needs of a growing number of people for whom the items sold in existing shops were difficult to access[43].” The target audience was therefore much broader than Bing’s. The reason given for this choice was the desire to make art accessible to as many people as possible. According to the author of the preface to Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), “the creation of the Maison Moderne had no other origin than the firm determination to satisfy an ideal that had been that of William Morris, our neighbors across the Channel, and which, until 1898, no one had succeeded in achieving among us.” This social commitment highlighted at the gallery’s opening can also be explained by the fact that a shop selling quality items at reasonable prices can expect to make more sales than a gallery like Bing’s, and therefore be economically viable. Indeed, the financial aspect of La Maison Moderne is an important factor to consider while Meier-Graefe’s ideas were honorable and his desire to fill the living spaces of modest households was commendable, he needed a certain amount of financial prosperity to make his venture a success. The social ideal of the Art Nouveau movement is thus subject to economic success, without which no creation and dissemination of new objects is possible. This financial health would also encourage the most renowned artists to want to collaborate with the gallery. These guiding principles were present from the outset in the gallery’s policy and were explained in the articles accompanying its opening[45]. In the preface to Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), the operating principles and the variety of objects sold are highlighted. A year after the opening, Max Osborn explained the gallery’s position in the Parisian art market and the role of its director:

“One of the most recent phenomena of the present day, in which art and craftsmanship are finally reunited after too long a separation, is the decorative arts bazaar, a hybrid establishment halfway between an art gallery and a department store, offering both luxury goods and everyday objects, and whose owner is an unusual combination of connoisseur, artist, art critic, patron, and businessman in the noblest sense of the word[46].“

Max Osborn also highlights the paradoxical nature of the situation of the Parisian decorative arts: the two most important establishments were run by Germans who were trying, in their own way, to ”root” Art Nouveau in France. Van de Velde mentions in his memoirs the strength of will shown by Meier-Graefe regarding his conception of the decorative arts, but expresses doubts about his ability to carry out a project of this magnitude:

“La Maison Moderne had to differentiate itself from Samuel Bing’s Art Nouveau galleries through the uncompromising nature of its program; the aim was to bring together that section of the public that felt attracted to an evolution in painting and sculpture towards more assured forms and essential qualities. Julius Meier-Graefe could carry out such a program. He certainly did not lack ambition, but he lacked the financial means and the perseverance necessary to devote himself solely to this mission[47].”

Van de Velde’s fears were also justified by the scale Meier-Graefe wanted to give his gallery. While opening his first establishment in Paris, he also wanted to create branches throughout Europe to promote modern industrial art[48].

Interior design of La Maison Moderne in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, 1900, reproduced in Henry Van de Velde Passion Function Beauty, published on the occasion of the eponymous exhibition at the Musée du Cinquantenaire in Brussels, 2013, Lanoo, Tielt, 2013. All rights reserved.

Meier-Graefe’s initiative was highly innovative in France at the time, and La Maison Moderne was to be the springboard for a new alliance between art, industry, and commerce. He sought to form the only trio capable of offering affordable objects and furnishings to a skeptical public and critics: the artist, the manufacturer, and the merchant [49]. Once his gallery was open, Meier-Graefe gradually withdrew from the management of Dekorative Kunst and L’Art décoratif, although the fact that the gallery and the magazines shared administrative offices on Rue des Petits-Champs and the frequency of his articles in both magazines indicate that this withdrawal was never complete. Although he readily presented himself as the director of La Maison Moderne and L’Art décoratif, he found it difficult to openly reconcile the management of a modern art gallery with writing articles in magazines that championed the same cause[50]. He managed to carry out a concerted campaign by using his real name at the head of La Maison Moderne and pseudonyms for the publication of his articles.

While the founding of Dekorative Kunst and then L’Art décoratif brought Meier-Graefe to the forefront of the Parisian art scene, the creation of La Maison Moderne distinguished him as one of the leading players in the art market at the beginning of the 20th century. He now had all the means necessary to disseminate his ideas through published writings and objects offered for sale. Furthermore, his position as gallery director allowed him to select the artists with whom he wished to collaborate, thereby establishing a Europe-wide creative network that helped fuel the climate of emulation that prevailed in the French capital at the time. However, his position as a defender of modern decorative art, determined to “declare war on French taste and the situation in France,” made La Maison Moderne a risky venture, which had to convert the Parisian public to modern taste as quickly as possible or face extinction.

Bertrand Mothes

Translation Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Cat. exp. The Origins of Art Nouveau: The Bing House, Antwerp, Fonds Mercator, Paris, Les Arts décoratifs, Amsterdam, Van Gogh Museum, 2004.

[2] Lee SORENSEN, “Julius Meier-Graefe,” Dictionary of Art Historians, [http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/meiergraefej.htm].

[3] City of Banat, now in Romania.

[4]Kenworth MOFFETT, Meier-Graefe as Art Critic, Munich, Prestel-Verlag, 1973, p. 9.

[5] Lee SORENSEN, “Julius Meier-Graefe,” Dictionary of Art Historians, [http://www.dictionaryofarthistorians.org/meiergraefej.htm].

[6] Exhibition catalog, Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909). Naturalisme et Art Nouveau, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, N. Chaudun, 2007, p. 126.

[7] Jean-Michel LENIAUD, L’Art nouveau, Paris, Citadelles & Mazenod, 2009, pp. 453-454.

[8] Exhibition catalog, Art nouveau: Symbolismus und Jugendstil in Frankreich, Stuttgart, Arnoldsche, 1999, p. 150.

[9] Catherine KRAHMER, “Meier-Graefe et les arts décoratifs, un rédacteur à deux têtes” in Alexandre KOSTKA, Françoise LUCBERT (eds.), Distanz und Aneignung, Relations artistiques entre la France et l’Allemagne 1870-1945, Berlin, Akademie Verlag, 2004, p. 232.

[10] Cat. Exp Georges Lemmen 1865-1916, Brussels, Crédit Communal, Ghent, Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, Antwerp, Pandora, 1997, p. 51.

[11] Henry VAN DE VELDE, Récit de ma vie. 1, Anvers, Bruxelles, Paris, Berlin (1863-1900), text compiled and annotated by Anne VAN LOO and Fabrice VAN DE KERCKHOVE, Brussels, Versa, Paris, Flammarion, 1992, p. 263.

[12] The conversation takes place in the music room of Van de Velde’s mother-in-law’s house, which he has just redecorated for Irma Sèthe, his wife Maria’s sister, with wallpaper featuring a dahlia pattern.

[13] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 448.

[14] Les origines de L’Art nouveau : la Maison Bing, op. cit., note 1, p. 236.

[15] MOFFETT, op. cit., note 4, p. 28.

[16] Julius MEIER-GRAEFE, “L’Art Nouveau. Das Prinzip,” Das Atelier, 1896, no. 5, pp. 2-4; translation by Edwin Becker in Les origines de L’Art nouveau : la Maison Bing, op. cit., note 1, pp. 129-131.

[17] MOFFETT, op. cit., note 4, p. 28. [18] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle. Photographic reproductions of the main works of contributors to La Maison Moderne.Commented by R. [Raoul] AUBRY, H. [Henri] FRANTZ, G.-M. JACQUES [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], G. [Gustave] KAHN, J. [Julius] MEIER-GRAEFE, Gabriel MOUREY, Y. [Yvanhoé] RAMBOSSON, E. [Émile] SEDEYN, Gustave SOULIER, G. [Georges] BANS, with nine additional illustrations by Félix VALLOTTON Les Métiers d’Art. Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, p. 11 [Preface].

[19] Julius MEIER-GRAEFE, “Dekorative Kunst,” Neue Deutsche Rundschau, June 1896, pp. 543-560.

[20] On Meier-Graefe’s pseudonyms, see KRAHMER, op. cit., note 9, pp. 248-249.

[21] Catherine Krahmer attributes the cover design to Van de Velde (KRAHMER, op. cit. note 9, p. 233), while Roger Cardon attributes it to Van Rysselberghe (CARDON, op. cit. note 13, pp. 445–446).[22] CARDON, op. cit. note 13, p. 176.

[23] VAN DE VELDE, op. cit. note 11, p. 267.

[24] VAN DE VELDE, op. cit. note 11, p. 277.

[25] LENIAUD, op. cit. note 7, p. 129.

[26] VAN DE VELDE, op. cit. note 11, p. 341.

[27] Van de Velde’s composition was used as the cover of L’Art décoratif until issue no. 24 of the magazine, in September 1900.

[28] KRAHMER, op. cit. note 9, p. 239.

[29] Julius MEIER-GRAEFE [n. s.], “Préface,” L’Art décoratif, October 1898, no. 1, p. 2.

[30] L’Art décoratif, December 1898, no. 3, n. p.

[31] Letter from Paul Signac to Charles Angrand, December 30, 1896, private archives, quoted in Paris-Bruxelles, Bruxelles-Paris symbolisme, art nouveau : les relations artistiques entre la France et la Belgique, 1848-1914, exhibition catalog, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, Antwerp, Fonds Mercator, 1997, p. 393.

[32] Nancy J. TROY, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1991, p. 32.

[33] “Meier-Graefe lässt sich, wenigstens vorläufig, auf solche Kompromisse nicht ein” (Max OSBORN, “La Maison Moderne in Paris,” Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, November 1900, vol. VII, p. 102).

[34] Stephen ESCRITT, L’Art nouveau, Paris, Phaidon, 2002, p. 316.

[35] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op. cit., note 18, p. IV [Preface].

[36] Art nouveau : Symbolismus und Jugendstil in Frankreich, op. cit.,note 8, p. 151.

[37] TROY, op. cit., note 32, p. 46.

[38] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op.cit., note 18, p. I [Preface]. This acknowledgement of Meier-Graefe’s contribution should be tempered: it appears that he himself wrote the preface to Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, as well as the commentary in the “Furniture” section, as he is mentioned on the title page as one of the contributors to the work, although none of the texts are signed with his name. However, he is undoubtedly the author of the commentary on metal objects and lighting fixtures, signed under his pseudonym G.-M. Jacques.

[39] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronique de l’art décoratif, La ‘Maison Moderne’,” L’Art Décoratif, September 1899, no. 12, p. 277. [40] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronicle of Decorative Art, The ‘Modern House’,” L’Art Décoratif, October 1899, no. 13, p. 51.[41] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronicle of Decorative Art, La Maison Moderne,” L’Art Décoratif, November 1899, no. 14, p. 96.

[42] Paris-Bruxelles, Bruxelles-Paris, op. cit., note 31, p. 392.

[43] TROY, op. cit., note 32, p. 43; ESCRITT, op. cit., note 34, p. 318.

[44] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op. cit., note 18, p. I [Preface].

[45] R., op. cit., note 3_9, p. 277.

[46] OSBORN, op. cit., note 33, p. 99.

[47] VAN DE VELDE, op. cit., note 11, p. 357.

[48] KRAHMER, op. cit., note 9, p. 240.

[49] Rossella FROISSART PEZONE, L’art dans tout. Les arts décoratifs en France et l’utopie de l’Art Nouveau, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2004, p. 69.

[50] KRAHMER, op. cit., note 9, p. 237.

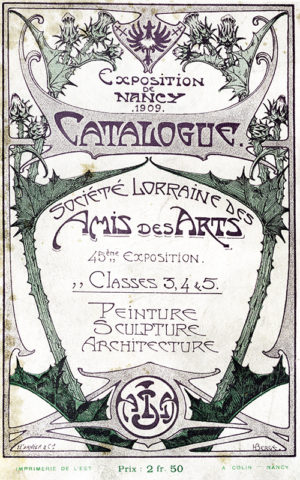

Nancy-Paris, Paris-Nancy – 1

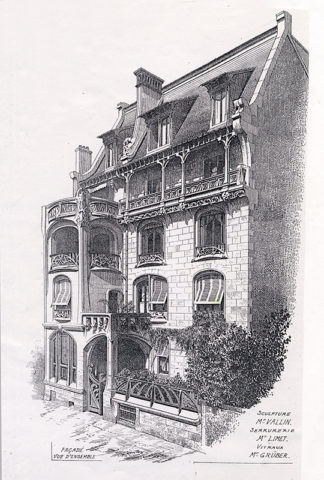

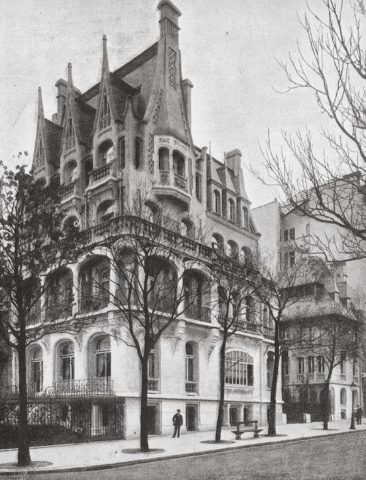

After mentioning the Vallin exhibition held at the Villa La Garenne in Liverdun during the summer of 2022, we begin a series of three articles showing some of the reciprocal influences between the artists of the Nancy School and those of the Parisian Art Nouveau, focusing on architecture.

The history of the interaction between the naturalist style of the Nancy School and the more linear styles of Parisian Art Nouveau and Belgian Art Nouveau has already been largely studied[1]. It is made of back and forth between the angles of this isosceles triangle, angles 320 km apart. If the people of Brussels had the initiative in the field of architecture, it is true that the people of Nancy became famous early on in the decorative arts by the quality and volume of their production. The relationship between these three creative centers was, however, asymmetrical, also reproducing the economic and political strength of each of these poles, for if local success was possible in Nancy and even more so in Brussels, recognition and the passage to a higher financial dimension went through Paris. Henry Van de Velde from Brussels and Émile Gallé and Louis Majorelle from Nancy understood this perfectly because they established themselves there as quickly as they could. If the graft did not take for Van de Velde, who was forced into exile in Germany, it succeeded commercially for Gallé, helped by his social and literary relations with the Parisian intellectual milieu, and even more so for Majorelle, thanks to the friendships and professional relationships he developed during his time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It was also at the ENBA in Paris that Nancy’s Victor Prouvé, Louis Majorelle and Jacques Gruber were trained, before they made their mark in the field of decorative art. As for Camille Gauthier, one of the most brilliant representatives of the second generation of the Nancy School, he was a student at the École nationale des arts décoratifs in Paris from 1891 before being hired by Majorelle in 1893. The question of this professional training was bitterly debated in Nancy, where despite the gradual but very slow transformation of a municipal school of drawing into a true school of fine arts, the new generation of Nancy architects, the one that was active in the 1900s, studied at the École nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where they often retained connections. These architects gained a prestige that their predecessors, trained in the established architectural firms and at the École Professionnelle de l’Est, did not have.

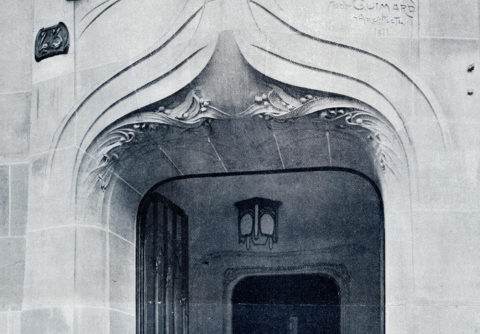

The influence of Nancy on Guimard

Known in Paris since the Universal Exhibition of 1878, famous since the exhibition La Pierre, le Bois, la Terre, le Verre organized by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in 1884, and finally crowned at the Universal Exhibition of 1889, Émile Gallé has largely contributed to a renewed use of the plant by the decorative arts. This influence is partly responsible for the numerous floral representations that were to be found in Parisian Art Nouveau, for example at Lalique, but also, almost unexpectedly, in the first part of Hector Guimard’s career. Until 1895, the latter practiced a style that was still eclectic but so recognizable and innovative that it can be described as proto-Art Nouveau. It is particularly evident in his creations of architectural ceramic panels, for which we refer to the third and fourth articles in our series on the Muller ceramic company.

Tympanum of the window of the 2nd floor of the right facade of the Hotel Jassedé by Guimard, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache in Paris, 1893. Two glazed earthenware panels. Photo F.D.

If the stylistic impulse did come from Nancy, we are witnessing here a complete reworking of the composition of these panels, which moves away from Emile Gallé’s descriptive use of botany. On the contrary, in a very short time, Guimard managed to produce perfectly mastered stylizations of floral motifs that had nothing to envy those presented a little later in 1897 in the portfolio La Plante et ses applications ornementales by Eugène Grasset and his students. The most visible Nancy imprint on a Guimard work is found on the ornamental fonts of the Sacred Heart school, 9 avenue de la Frillière, Paris XVIe, in 1895. The capitals of the columns dividing the large bays of the second floor into three have a very recognizable leaf and flower motif of the thistle, a plant not directly related to the iconography of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

.

Capital of the cast iron columns of unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the windows of the second floor of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

This plant has been the emblem of the city of Nancy since the 15th century, appearing on its coat of arms along with the motto “non inultus premor”. It has thus become a naturalist identification motif that Nancy’s inhabitants have used extensively and continuously in all branches of decorative art.

Large silver thistle brooch by Ferdinand Kauffer, model created around 1886. Phototype published in La Lorraine Artiste in 1894, reproduced in Martin, Étienne, Bijoux Art nouveau Nancy 1890-1920, éditions du quotidien, 2015.

Project for the entrance portico of the École de Nancy at the 1902 exhibition of decorative art in Turin (not realized) by Émile André. Watercolor drawing, Musée de l’École de Nancy.

Catalog of the SLAA exhibition at the International Exhibition of Eastern France in 1909, drawing by Henri Bergé. Private collection.

Even more interesting, the inclined cast iron pillars that support the second floor of the Sacred Heart School have been decorated with motifs that are no longer descriptive this time but very clearly evoke the bud and indentation of the thistle leaves.

Cast iron pillar by an unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the courtyard of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

From his period strictly speaking Art Nouveau, the one that begins in 1895 with the Castel Béranger, Guimard abandoned the naturalistic and botanical representation to keep only the spirit. He thus adhered to the aesthetic advocated by the Brussels-based Victor Horta, while inventing – and constantly reinventing – his own style, soon to be copied by a host of followers. However, Guimard did not totally banish the plant from his creation. It may have reappeared from time to time, but always in a form that is not botanically identifiable. Thus, we find indentations applied to the base of the rear pillars of the A aedicula (1900)[2].

Rear pillar of the A-aedicula of the Abbesses station. Photo F.D.

Leaves and fruits carved on the lintel of the entrance door of 43 rue Gros (1909-1911.

Entrance door of the building at 43 rue Gros in Paris by Guimard (1909-1911). La Construction moderne, February 9, 1913.

The ceiling light of the hallway is visible on the previous picture. It is part of the Lustres Lumière created by Guimard from 1909. On its bronze plates, we can also see leaves or blades of grass intertwined.

Bronze element of the Lustres Lumière. Photo F.D.

Later, in 1922, on the jambs of the Grunwaldt tomb, in the new cemetery of Neuilly-sur-Seine, the sculpted decoration mixes laurel and palm branches, two common species in the cemetery repertoire. These two plants, which are also used in the decoration of this small monument, symbolize the glory of the deceased.

Carved plant decoration on a jamb of the Grunwald burial, 1922. Photo F.D.

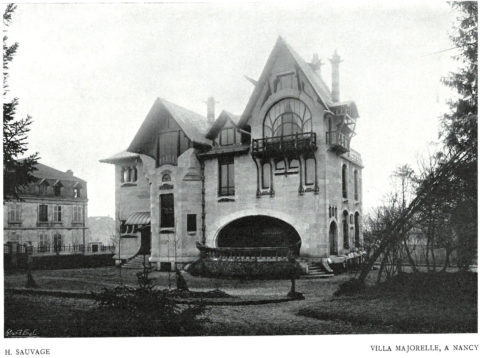

2- The influence of the Parisian Art Nouveau and of Guimard in Nancy

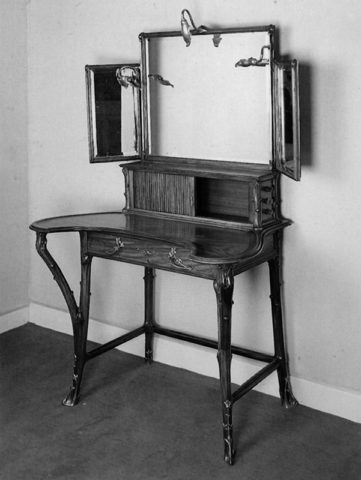

For his part, Guimard never built or decorated anything in Nancy. Moreover, at the present time, no archive allows us to say that he even visited the city, and yet his influence on the city is very real. It was realized through the intermediary of fellow Parisian architects who knew how to compose with the naturalism in vogue in Nancy. The first of these was of course his friend Henri Sauvage, who built the villa of furniture manufacturer Louis Majorelle in Nancy. This choice of a young, inexperienced Parisian architect is significant, as Majorelle was both a bridgehead of the Nancy style in Paris and a bridgehead of the Parisian style in Nancy. An emulator of Gallé in the field of cabinetmaking from 1895 on, he did not give his style a truly personal dimension until shortly before the 1900 World’s Fair, when he moved closer to the Parisian style. This orientation was undoubtedly favored by the work of the young Camille Gauthier, trained at the National School of Decorative Arts and hired by Majorelle from 1893 to 1900. It was also inspired by certain Parisian models such as this dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, whose legs split into two to support a console

Dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, 1898. Museum of the École de Nancy. Photograph taken from the book Majorelle by Roselyne Bouvier. La Bibliothèque des arts, 1997. Photo A. Fellmann.

This arrangement of the legs, provided with thorns on the Plumet/Selmersheim dressing table (and thus clearly designated as plant stems in the manner from Nancy) was largely taken up again a little later on part of the furniture presented by Majorelle at the World Fair of 1900. His furniture then presented a more continuous dynamic line (more “Parisian”) underlined by a water lily stem in gilded bronze.

Desk with water lilies by Majorelle. Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1900. Portfolio Meubles de style moderne Exposition Universelle de 1900, Charles Schmid éditeur. Private collection.

Majorelle also collaborated with the Parisian Henri Sauvage in 1898 for three lounges of the Café de Paris (41 avenue de l’Opéra).

Ceiling of one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

Mantelpiece in one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

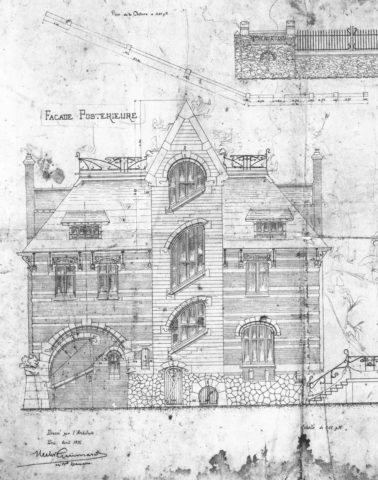

This Parisian realization of Majorelle preluded the construction of his villa in Nancy designed by the same architect in 1901-1902 with the intervention of two other Parisians: the ceramist Alexandre Bigot and the young painter Francis Jourdain, son of the architect Frantz Jourdain, another friend of Guimard.

North facade of the Villa Majorelle in Nancy, excerpt from an article by Frantz Jourdain in L’Art Décoratif, August 1902. Digital library limedia.

It is easy to recognize in this northern facade of the Majorelle villa a clear influence of the rear facade of Villa Berthe built by Guimard at Le Vésinet in 1896.

Plan of the rear façade of Villa Berthe, dated 1896.

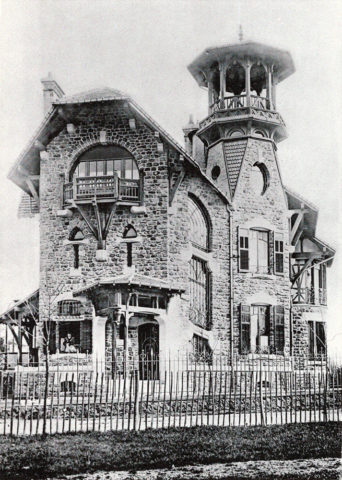

Another Parisian architect, Jacques-René Hermant, came to Nancy relatively early to build the Maison Luc in 1901-1902.

Victor Luc House, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

Its symmetrically ordered facade in bays and levels conceals beautiful details such as the capitals of the porch columns, the ceramics of the cornice and the ironwork with its linear curves. Inside, a glazed stoneware staircase by Gentil & Bourdet is one of the most remarkable achievements of this Parisian firm whose protagonist, François Eugène Bourdet, was a young architect from Nancy.

Victor Luc house, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Detail of the porch. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

These last two residences influenced Nancy architects and the Villa Majorelle even became one of the driving forces of modern architecture in Nancy. But in parallel to this Parisian trend, another trend, more locally inspired, was led by the Vallin-Biet duo who had just completed the Biet building. For this local trend, the filiation with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was also present, but the structure of the buildings was more unitary and organic. As we will see in a later article, Guimard and Vallin were able – separately – to exploit certain themes such as the representation of the deformation of matter.

Biet building, 22 rue de la Commanderie in Nancy, 1901-1902. Portfolio Motifs d’architecture moderne, undated (ca. 1905).

Many Nancy architects, such as Émile André and Lucien Weissenburger, then took decorative details from both buildings. On the Houot house or on the Fernbach villa of Émile André, the windowsills are borrowed from the Majorelle villa of Sauvage.

Window sill of the villa Majorelle à Nancy by Henri Sauvage, 1901-1902. Photo F.D.

Window sill of the Houot house, 92 bis quai de la Bataille in Nancy by Émile André, 1903. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

The same architect, Emile André, borrowed the peristyles of the third floor balconies of his buildings at 69 and 71 Avenue Foch in Nancy from another Parisian architect, Charles Plumet, a precursor of the Art Nouveau style.

Lombard building (left) at 69 avenue Foch in Nancy (1902-1903) and France-Lanord building (right) at 71 avenue Foch in Nancy (1902-1904), Émile André. Photo F.D.

Plumet had developed these peristyles on several of his Parisian buildings from 1897 (36 rue de Tocqueville) and had reused them on numerous occasions.

Private mansion by Charles Plumet, at the corner of 28 avenue Foch and 90 avenue Malakoff in Paris, seen from the avenue Malakoff side, 1900. Photo published in the German magazine Die Architektur des XX. Jahrhunderts. Private collection.

Also in the Villa Majorelle, the frame of the first floor doors, glazed over two-thirds of the height, is of particular interest. At the base of the glazed part, a small wood is obliquely detached from each side jamb, then becomes vertical and joins the upper crosspiece, evoking a rejection born of a trunk. Moreover, this glazed part is intersected at the top by a simple horizontal line.

Door of the dining room of the Villa Majorelle by Henri Sauvage. Photo F.D.

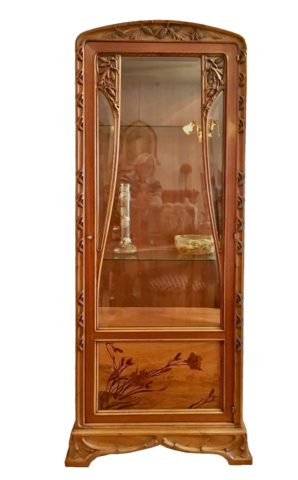

Louis Majorelle used this layout on a series of display cases with or without the addition of naturalist decoration.

Louis Majorelle, pinecones display case, model n° 244, height 1 m 90, sold 900 F-gold in 1914. Photo website Anticstore, Galerie Vaudémont, Nancy. All rights reserved.

This arrangement is directly reproduced on the doors of several of Guimard’s showcases, the earliest of which is reproduced in an article by Frantz Jourdain published in the first issue of the Revue d’Art (for which Guimard had designed the cover) in November 1899.

Little table and display case by Guimard photographed at Castle Béranger. Photo published in the Revue d’Art n°1 in November 1899.

This door is more visible on this later window that was in the Guimard Hotel.

Display case by Guimard having been in the Guimard Hotel 122 avenue Mozart. Private collection.

Other influences of Guimard’s work exist in Nancy, even if they are not in very large numbers. Rather, they came about through the publication of his work in magazines and through the travels of Nancy residents to Paris. It is undoubtedly by one or the other means that Joseph Hornecker, a young Alsatian architect who arrived in Nancy in 1901 and associated with Henri Gutton, was inspired by the Castel Henriette in Sèvres for the Villa Marguerite, built in the Parc de Saurupt in Nancy in 1904.

Villa Marguerite in the park of Saurupt. Portfolio Nouvelles constructions de Nancy. Private collection

Walking through the streets of Nancy, one can also find ornamental castings by Guimard on the windows of about fifteen houses or buildings, many of which are the work of the architect Lavocat. However, these were orders placed directly with the Saint-Dizier foundry by a small number of Nancy architects before the First World War and therefore without any intervention by Guimard.

Large GG balcony and return, building 31 rue Anatole France in Nancy. Photo F.D.

It is not possible to attribute to the influence of Guimard alone the numerous linear-style ironworks that can also be found in Nancy, such as that of the Immeuble Kempf, 40 Cours Léopold by Félicien and Fernand César (1903-1904), or those of the houses at 16 and 20 rue des Bégonias by Désiré Bourgon. But, in addition to the marquise of the Villa La Garenne which was the subject of a previous article, there is a well-known example of a direct transcription of a work of ironwork by Guimard: the door of the Castel Béranger copied by the Nancy locksmith Lucien Collignon for the door of his own house at 55 rue de Boudonville in 1905, that is to say, ten years after Guimard’s.

Door of the maison Collignon, 55 rue de Boudonville in Nancy. Photo all rights reserved.

More anecdotally, on Boulevard Lobau, the counter and its lettering of the commercial building of the coal merchant Jules Kronberg are also to be credited with the influence that Guimard’s style had in Nancy. This “discrepancy” is all the more surprising since Kronberg was a tenant and client of Vallin, who lived almost opposite.

Also in the field of ironwork, the young Parisian Edgard Brandt (1880-1860) had a first creative period in the Art Nouveau style. When he worked in Nancy, he was able to adapt to the local style. At the request of the Nancy architect Joseph Hornecker, he was commissioned in 1907-1909 to carry out a major program at the new headquarters of the SNCI bank (exterior ironwork, lobby and vault).

Hall of the Nancy bank SNCI, architect Joseph Hornecker, 1907-1909, ironworks with pinecones by Edgard Brandt.

For the same Nancy architect and also in 1907, Brandt executed the banister of the main staircase of the town hall of Euville in Meuse. These two creations, both naturalistic (pine cones for the SNCI) and symbolist (oak for the town hall of Euville) are completely in the Nancy style and prelude the gradual evolution of Brandt towards a more refined modern style and then towards Art Deco.

Edgard Brandt, oak leaves and acorns railing of the Euville town hall. Photo: Cédric Amey, under Creative Commons license.

Because of the vigor of the Nancy artistic community, these stylistic exchanges between Nancy and Paris were not solely to the benefit of the capital city and, as we will see in a later article, the Nancy style even made a strong comeback in Paris thanks to the department stores and in particular the powerful Nancy chain of Magasins Réunis.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Thanks to Fabrice Kunégel who pointed out the similarity between the woodwork of the interior doors of the Majorelle villa and those of certain Guimard windows. Thanks also to Koen Roelstraete for his research on the pine cone window of Majorelle.

Translation : Alan Bryden

Notes :

[1] Thanks to numerous articles and the fascinating Paris-Brussels, Brussels-Paris exhibition of 1997 at the Musée d’Orsay and the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent.

[2] Let us point out for the sake of argument that the interpretations we can give of Guimard’s motives are our own. If we think that they can be shared by other observers, we do not want to impose them on anyone.

Membership fee 2022 : The Cercle Guimard innovates with online payment

If you have not yet renewed your membership for the year 2022, you can now do so online thanks to Pay Asso.

The Cercle Guimard took advantage of the change of banking institution at the beginning of the year to equip itself with this secure and easy-to-use payment tool.

Now all you have to do is click on the proposed link, choose the membership formula and pay with your credit card :

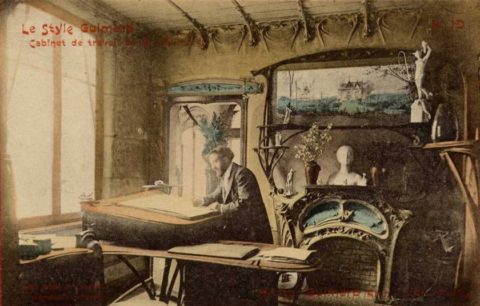

Hector Guimard’s office at Castel Béranger. Postcard Le Style Guimard n°10. Private collection

Our recognition of general interest allows the Cercle to issue tax receipts if memberships do not benefit from compensation.

Also, as of this year, we are removing the few rewards offered so far and will now provide all our members with a tax receipt. This allows natural persons to deduct 66% of the amount of the membership from its taxes and for legal persons 60% (See the Membership page for more information).

We have changed the names of some rates and created an additional Benefactor category to standardize our formulas.

Members who have already paid their 2022 membership fee will receive a tax receipt by e-mail in the coming weeks.

For any questions, do not hesitate to contact us at infos@lecercleguimard.fr.

Your membership of the Cercle Guimard is an essential support to carry out the research and protection of Hector Guimard’s heritage.We thank you very much for your support and loyalty.

The Cercle Guimard Bureau

The Cercle Guimard needs you!

Edicule B, Porte Dauphine station. Photo by Arnaud Rodriguez – Le Cercle Guimard

SUPPORT THE CERCLE GUIMARD!

You are sensitive to the work of Hector Guimard,

you think this architect deserves to be recognized,

you support the Guimard Museum project.

You have a draft article or a research topic,

you own furniture, objects or documents related to Guimard,

you are a photographer and you would like to collaborate to the work of

the Cercle Guimard,

you are an archivist at heart and you want to invest in our archive center,

you are comfortable with the use of the Internet and you wish to assist our webmaster,

you are a lawyer or jurist and you want to defend the interests of the Cercle Guimard.

You simply wish to support the association and participate in its projects.

So join the great Art Nouveau family by being a member or donator of the Cercle Guimard!

To contact us : infos@lecercleguimard.fr

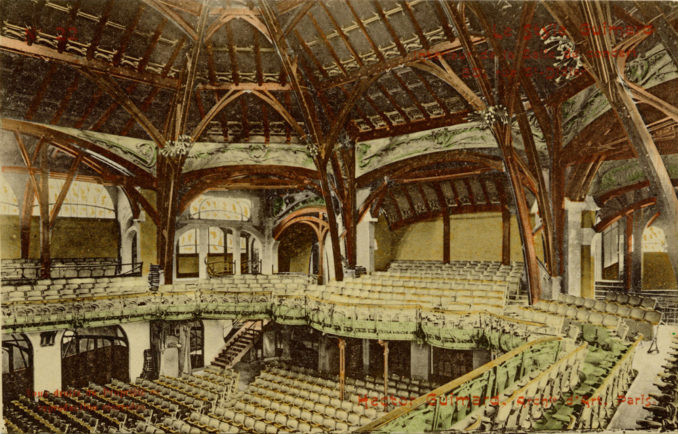

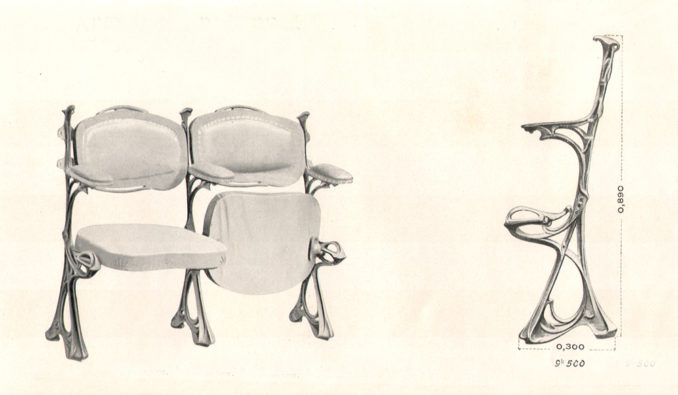

The theatre armchairs of the Salle Humbert de Romans and their re-discovery