Author: f.descouturelle

Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique in 1897 and other architectural achievements in glazed ceramics

Our previous article showed that the ceramic decorations at Castel Béranger are only partially attributable to the Bigot company, which specialized in glazed stoneware. By looking at a contemporary creation, that of the stand presented by Guimard at the Exposition de la Céramique in 1897, we continue to clarify the roles of the ceramic companies that Guimard called upon, the role of the modellers who assisted him, and the nature of the products of their work (stoneware or terracotta). Some ceramic decorations made in the filiation of those of Castel Béranger, but for other constructions, will also be mentioned.

The panel with the cat arching its back which we presented previously can be found (probably before its final installation on the Castel Béranger) included in Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique et de tous les Arts du feu[1] in 1897.

Panel with the cat arching its back, c. 1897, glazed ceramic by Gilardoni & Brault, placed under the oriel on the left corner of the second floor of the building on street. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

This exhibition mixed all the products of ceramics (and glassware) whether they are building materials, technical materials or artistic expressions. For the latter, in addition to the indispensable retrospective section, we find the names of those who will soon express themselves in a remarkable way in the modern style: Bigot[2], Lachenal, Delaherche, Massier, Dalpayrat, but also larger and more industrial companies with necessarily eclectic productions such as Loebnitz, Keller & Guérin, Muller, Gilardoni & Brault[3]. Of course, the Manufacture de Sèvres is widely represented[4].

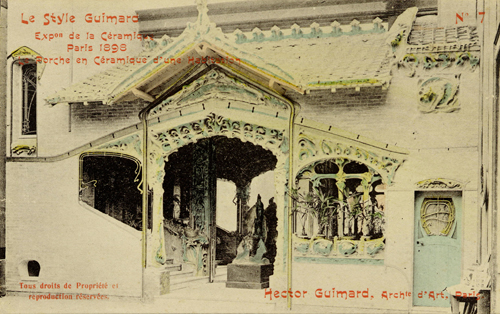

The only picture we have of the Guimard stand is on one of the postcards of the series Le Style Guimard[5] .

Guimard’s stand at the Exposition de la Céramique et tous les Arts du feu in 1897: “Ceramic Porch of a Dwelling”. Old postcard n° 3 of the series Le Style Guimard, wrongly dated 1898. The cat arching its back is on the top right. Private collection.

Since the Parisian public could only then incidentally know of the existence of the Castel Béranger under completion, this stand was the first public manifestation of Guimard’s modern style and certainly caused a visual shock by its radically innovative aspect. More than just a stand, this presentation is a true architectural achievement presenting a building porch[6] leaning against a blind wall decorated with mirrors. Its walls are made of brick and Guimard, by adding an awning to the tiled roof, has deployed an important combination of ridge, cornice and tympanum which surmounts the rich framing of the openings with clerestory, including a mullioned window and window box in the lower part. The decoration continues inside with a console and pilaster at the start of the staircase, panelling that accompanies the ascent of the steps and probably a ceiling.

What Future for the Hotel Mezzara?

On the website of La Tribune de l’Art, a specialised news magazine, in an article dated 24 April, Bénédicte Bonnet Saint-Georges gives a complete history of the Guimard Museum project carried by Le Cercle Guimard and Fabien Choné. At the end of this account, the journalist questions the Ministry of Culture on the museum potential of the Hotel Mezzara, recalling precisely the proposal of the Cercle Guimard. She also questions the Ministry of Finance about the call for tenders — still to come — and its selection criteria.

photo Bruno Dupont

For the Cercle Guimard and its project, the support of La Tribune de l’Art is a strong sign. This survey can only encourage and comfort the community of enthusiasts who see the Hotel Mezzara as the future standard bearer of French Art Nouveau.

A must-read.

The ceramic decorations of the Castel Béranger

The Castel Béranger’s ceramic decorations are usually renowned for being made of glazed stoneware and for having been produced by the Bigot company. But the discovery of new documents allows us to revise this opinion. We do not discuss here the stoneware mosaics that are mentioned in the article on the decoration of the vestibule. The latter, as well as the article on the panel with the cat arching its back, have been modified.

The Castel Béranger (1895-1898), an apartment building intended for the lower middle class, bore the hopes of a young architect anxious to make a name for himself through a media stunt and thus escape the fate promised to architects who had not graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts: a laborious and obscure life. Its composite and colourful facade bears the mark of the architect’s sudden conversion from a neo-Viollet-le-Duc style to Art Nouveau. It uses many materials: dressed stone, millstone, red brick, glazed brick, ironwork, ornamental cast iron, stained glass and architectural ceramics.

For the latter material, Guimard turned for the first time to two new companies, to the detriment of Muller & Cie[1] who had previously supplied him with the glazed ceramic panels he used to decorate his buildings. Of these two companies, the oldest and largest in terms of production volume is Gilardoni fils, A. Brault et Cie [2]. The most recent is A. Bigot et Cie[3], which has positioned itself exclusively on glazed stoneware[4]. Bigot was then very attentive to new stylistic trends and Guimard seems to have wanted to experiment with this new material with him. The list of contributors he included on one of the first plates of the Castel Béranger portfolio mentions these two companies in the following terms:

Photomontage by computer graphics of an excerpt of the plate from the Castel Béranger portfolio containing the names of the companies that executed the models. Private collection.

We are certain of Bigot’s participation on two supplies that received his signature: the decoration of the vestibule (signed at the bottom of each panel) and the fireplaces in some dining rooms.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Five: Muller “all fire and flame”

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry and its relationship with the Art nouveau movement concludes with a study centred on its production of modern style fireplaces. We thus offer ourselves an escape from Guimard’s creations since, to our knowledge, he did not ask Muller to create and even less to edit objects of the fixed decor. But we take the opportunity of this article to reveal the existence of fake fireplaces of a well-known model of Muller, one of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

The fireplace — the hearth — has always symbolized at the same time the place of domestic life and where the family unit gathers around when it brings a little comfort during the cold months of the year. In the 19th century, as the dining room became the core bourgeois reception room, the fireplace was an essential part of the decor, even if its functional role diminished as innovations progressed, such as the stove and then the salamander, which was adapted in front of its hearth, and especially central heating by radiators or hot air ducts. The fireplace was then reduced to a role of auxiliary or mid-season heating. However, neither the owners, nor the decorators, were ready to abdicate its presence in the house and its role in social representation[1].

Art nouveau style fireplaces

Art nouveau will be the style in which the formal aspect of the fireplace will literally explode. From 1895 to 1900, modern models were few, and above all not very visible because they were intended for private interiors, without mass production, with the exception of a few rare models presented in specialized magazines or official trade shows.

In the French sections of the 1900 Universal Exhibition, one can first come across fireplaces whose structure is still clearly neo-Gothic or neo-Renaissance but whose decoration is simply modernized, such as those by William Haensler, Georges Turck or the stand of the Professional Schools of the City of Paris. Other fireplaces are clearly Art nouveau in style, such as those in the dining rooms of the Épeaux and Dumas companys, both in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which reinterpret the naturalistic style of the Nancéiens in superabundance.

Fireplace from the dining room of the Dumas company, presented at the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition. Currently exhibited in the villa Cochet (Champagnes Pommery) in Reims. We don’t know the name of the ceramist who provided the insert. Photo author.

The fireplace presented by Louis Bigaux is more personal, as is that of Henri Bellery-Desfontaine, who gives pride of place to painting on its large hood.

But real stylistic innovations are also present at this exhibition, within the class 66 (fixed decoration of public buildings and homes) with the wooden fireplace from Pierre Selmersheim’s stand and that of Guimard in bronzed cast iron and enamelled lava where structure and decoration merge into organic forms.

Fireplace from Pierre Selmersheim’s stand, presented at the 1900 Universal Exhibition. Portfolio Exhibition of 1900 Decoration and Furniture, 2nd series. Forney Library.

For a few years, unique pieces as exceptional as the fireplace in the Masson dining room in Nancy will be produced for wealthy sponsors. They are obviously out of reach for the vast majority of bourgeois budgets.

Fireplace from Charles Masson’s dining room in Nancy by Eugène Vallin and Victor Prouvé, 1903, presented at the Ecole de Nancy Museum. Billed 4683.45 F-gold by Vallin, this fireplace probably never experienced an actual fire because from the beginning an electric resistance was placed in front of its hearth. Photo Philippe Husson.

The purchase of a fireplace, part of the fixed decor of a residence, only concerns owners in the case of a new construction or the modernization of an old dwelling, and not the tenants. This is why the furniture sets sold by cabinet making firms on catalogue usually do not include them. They do, however, offer them at widely varying prices. The Épeaux house, for example, which on the eve of the First World War still hadn’t managed to sell its 1900 exhibition fireplace, displays it in its catalogue at 4,800 F-gold.

Fireplace mantel from the dining room of the Épeaux company with an apple blossom design in Cuban mahogany and gold wood, presented at the 1900 Paris World Exhibition. Private collection.

The Art Nouveau glazed stoneware fireplaces

Even though marble workshops produced carved mantels on a production line in a few tirelessly repeated models, any fantasy or simply any novelty would be all the more costly as an expensive material must be crafted by a specialized worker. Manufacturers of tile products, manufacturers of glazed stoneware tiles, as well as industrial stove makers therefore quickly understood that, thanks to glazed ceramics and especially glazed stoneware, they could go beyond the simple supply of tiles intended to decorate mantelpieces to mass produce the mantels themselves, made up of a few easily assembled elements offering excellent thermal qualities. In a simple horseshoe pattern around the hearth and with only the obligation to surmount it with one or more shelves and possibly to provide space for accessories (shovels and pokers), they could give free rein to the imagination of designers. This type of article is then of a sufficiently interesting profit for most manufacturers to launch on the market models of glazed stoneware fireplaces of modern style. Below are a few examples.

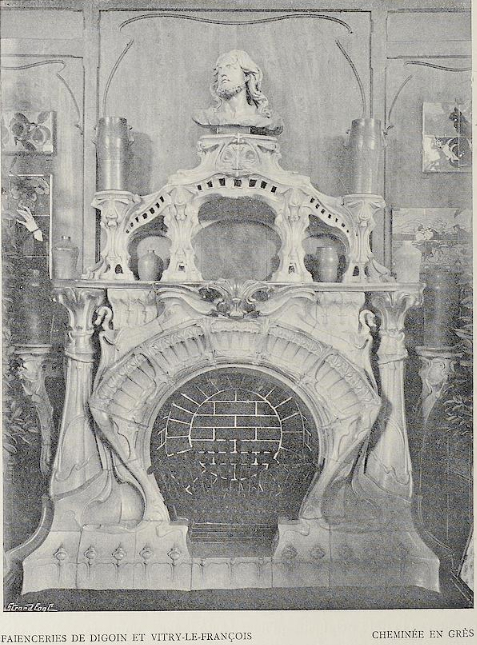

The earthenware factory of Sarreguemines, in the German-occupied Lorraine region, which for commercial reasons hid behind the names of its French plants in Digoin and Vitry-le-François, presented an Art Nouveau style glazed stoneware fireplace at the 1900 Universal Exhibition by the architect Victor Bury. The beautiful corolla motif of its central part is unfortunately weakened by the modeling of the rest of the mantel, consoles and shelves that the heat of the hearth seems to have melted away.

Fireplace from Sarreguemines in glazed stoneware, presented at the 1900 Universal Exhibition. Photo internet.

The same fireplace at the Sarreguemines earthenware museum. Photo from insming.centerblog.net

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Four: Muller and Hector Guimard, other achievements.

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. In this fourth article, we try to identify the collaboration between Muller & Cie and Hector Guimard.

The Villa Charles Jassedé

Shortly after the construction of Louis Jassedé’s private mansion began in 1893, rue Chardon Lagache in Paris, Guimard began the construction of a villa in the Paris suburbs for Charles Jassedé, Louis’ cousin, at 63 route de Clamart (currently avenue du Général-de-Gaulle) in Issy-les-Moulineaux. As usual, he pushed the building back to the edge of the plot so that he could make the most of the garden.

Villa Charles Jassedé, 63 avenue du Général-de-Gaulle at Issy-les-Moulineaux. Photo Wikicommons, crédit : Patrbe/CC BY-SA.

Built on a much smaller budget than the Jassedé Hotel, this country house nevertheless presents some picturesque details such as its two deflections on the street façade, the high chimneys and the corbelling (more symbolic than real) of the straight span of this facade by oblique irons.

Villa Charles Jassedé, 63 avenue du Général-de-Gaulle at Issy-les-Moulineaux. Photo internet, Laurent D. Ruamps.

On this occasion, Guimard does not create new models of architectural ceramics, but simply draws from those he already has published at Muller & Cie and even from those in the catalogue. He therefore reuses his metope no. 13 to girdle the base of the corbelled bay (five metopes on the street side, seven on the right-hand side of the façade), also taking up the framing by angle irons and iron blades as for the lintels of the windows of the Hotel Jassedé.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Three: Muller and Hector Guimard, Hotel Roszé and Hotel Jassedé.

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. In this third article, and then in the next one, we address the collaboration between Muller & Cie and Hector Guimard.

Our articles will not present all of Guimard’s architectural ceramic designs known and intended for Muller nor all of the instances of use of his decorative panels by other architects. This exhaustive study is being carried out in parallel for the constitution of a specific repertory.

Hector Guimard is a special case among the modern architects who supplied models to Muller & Cie, since he called upon the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry for the decoration of his first villas built in the West of Paris in the early 1890s. These orders immediately led to the publication of models. But curiously, as soon as the Castel Béranger was built in 1895-1898, Guimard no longer seemed to place orders with Muller & Cie and turned to Gilardoni & Brault and Alexandre Bigot. Almost a decade later, however, 14 of his models still appear in Muller & Cie’s 1904 catalogue n° 2.

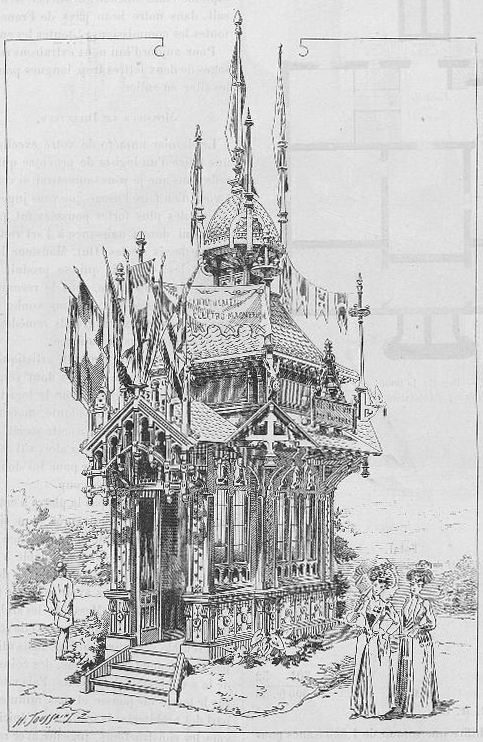

From his first known construction, a modest pavilion praising the therapeutic methods of electricity and electromagnetism[1] for an obscure Ferdinand de Boyères at the 1889 Universal Exhibition, Guimard used ceramics[2] to decorate the panels inserted in the joinery. The professional magazine La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890 gives an engraving of it (probably from a photo) but we do not know which ceramic models were used or who was the supplier.

Guimard’s “Pavillon for the application of electricity to medicine” at the 1889 Universal Exhibition. Illustration by Henri Toussaint published in La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890. The ceramic decorations are on the basement as well as on the panels separating the windows. Gallica BNF website.

Hotel Roszé

Two years later, in 1891, for the Hotel Roszé at 34 rue Boileau in the 16th arrondissement, we have the certainty of a real collaboration between Guimard and Muller & Cie thanks to the presence of several panels of the Hotel on the 1904 catalogue n° 2. At that time, Guimard was only 24 years old and he was far from having the notoriety that would be his from the Castel Béranger. The novelty of his models, which seems less obvious today, must have been enough for Louis d’Émile Muller to feel that this young architect deserved attention.

The Hotel Roszé, 34 rue Boileau in Paris, photograph taken in 1975. At that time the ceramic panels on the front and back facades were masked by a coat of paint. ©Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

The friezes on either side of the lintel[3] of the first-floor window on the left-hand span of the street facade are clad with four-part panels showing a branch from which a blue and a white flower emerge alternately.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Two: Muller and Art Nouveau

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. The first article summarized the history of the company. In this second article we look more precisely at the collaborations with the artists and architects of this artistic movement. The third and fourth article will focus on Hector Guimard’s model editions at Muller & Cie and the fith on the fireplace sector.

Following the death of Émile Muller in 1889 after the Universal Exhibition, his son Louis d’Émile Muller took over the management of the company. The latter developed an artistic sector by publishing contemporary artists and intensifying relations with architects for the creation of new models to be published or not.

The private mansion known as La Pagode, built in a Japanese style in 1895-1896 by the architect Alexandre Marcel for the director of Bon Marché, at 57 rue de Babylone in Paris, is a good example of this. Only a part of the enamelled stoneware decoration can be found in the catalogue.

Two panels from the decoration of La Pagode, architect Alexandre Marcel, 1895-1896, 57 rue de Babylone, Paris. Catalogue Muller et Cie No. 2, 1904, pl. 15. Private collection. Each panel: 12 kg; red or white terracotta: 15 F-gold; enamelled terracotta: 30 F-gold; unenamelled stoneware: 20 F-gold; enamelled stoneware: 40 F-gold.

Among the young designers who came into contact with Muller & Cie many will participate in one way or another in the Art Nouveau artistic movement, focused on decorative art and architecture. Their work will generate a large number of new models that are likely to be reused by others. It is therefore essential for a company such as the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry to keep up to date and to be able to supply without delay those architects, contractors and decorators who are not themselves creators but who wish to give their work a modern look. The Muller & Cie catalogues will therefore include a significant number of Art Nouveau style models.

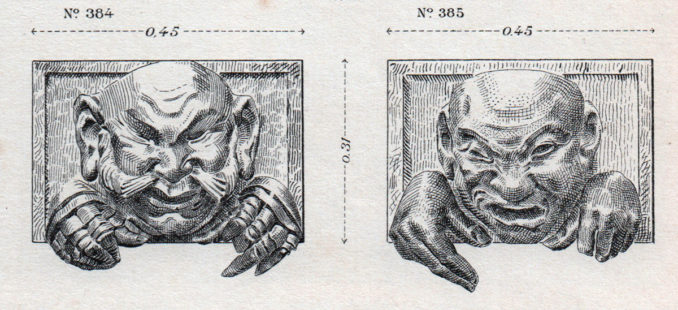

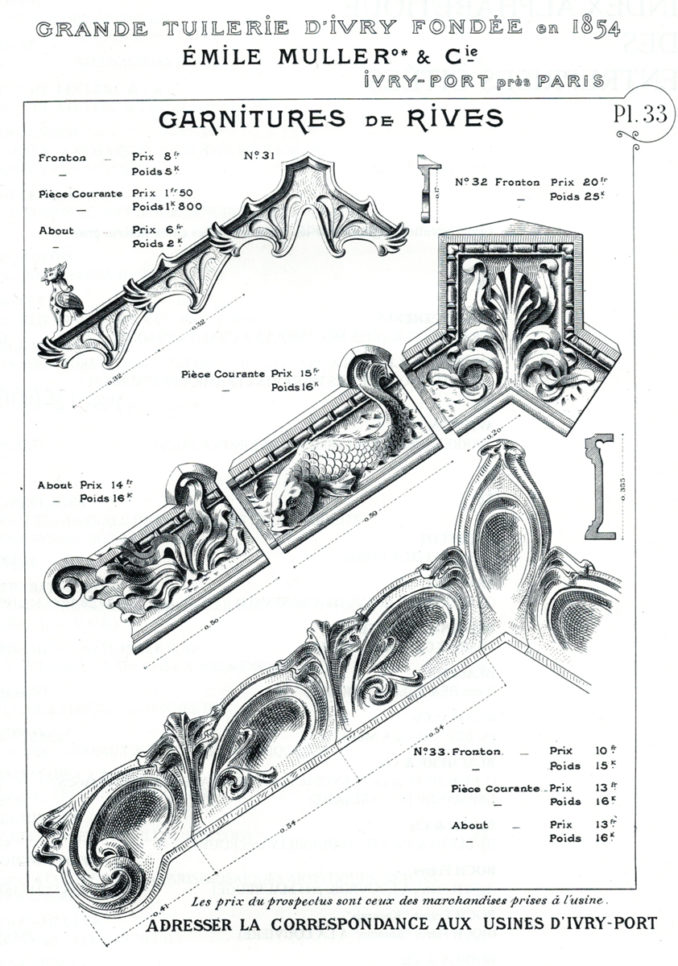

Catalogue n° 1, which includes building materials with bricks and tiles, is enriched with models in which Art Nouveau makes a discreet appearance on plate 33 with two models of verge tiles and pediments which frame a more traditional neo-Renaissance model. These are models not signed by an architect and were therefore purchased from an anonymous industrial artist.

Verge tiles from the Muller & Cie catalogue n° 1, pl. 33. 1903. Reproduced from La Céramique architecturale à travers les catalogues des fabricants, p. 167.

We will rely more readily on the plethoric catalogue no. 2 of 1904, which is mainly devoted to products for exterior and interior architectural decoration, but which also includes vases, pieces of art and trinkets. Many well-known artists can be found in this catalogue, and among those who worked in the Art Nouveau movement are the sculptors Pierre Roche, Ringel d’Illzach, Jean Dampt, Timoléon Guérin and Louis Chalon.

The Grande Tuilerie at Ivry — Part One: the Muller company

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his work in the field of Art Nouveau. In this first article, we address the history of the company and the variety of his works. A second article will focus on Muller’s production in the Art Nouveau style, the third and fourth articles on Hector Guimard’s model editions and a fith on the fireplace sector.

Émile Muller (1823-1889) was born in Altkirch in Alsace, near Mulhouse. Coming from a well-to-do family, he completed his studies in Paris, graduating from the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufacture in 1844. He was then a professor of civil engineering for 24 years, starting in 1864.

-

Portrait of Émile Muller. Documentation center of the École Centrale Paris.

His involvement in the field of education is also shown by his participation in the foundation of the Special School of Architecture[1] and the (Paris) Free School of Political Science (now Sciences-Po). He also presides over the Society of Civil Engineers, where he will have Gustave Eiffel as his successor. Motivated by social ideas, after having built several public facilities, Émile Muller built a workers’ housing estate in Mulhouse in 1853, the first French experiment in decent family housing with gardens. He was also committed to protecting workers from industrial accidents.

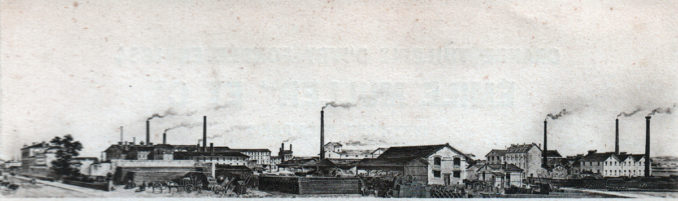

The following year, in 1854, Émile Muller founded a tile manufacturing company in Mulhouse, then a few months later bought a large piece of land to found the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry (the large Ivry tile plant), located on the banks of the Seine, on the Paris-Basel main road, near clay quarries in the southern suburbs of Paris. A showroom and sales room will be opened at a date that we do not know, but probably much later, at a more prestigious address: 3 rue Halévy, near the Paris Opera House.

General view of the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry. The front of the factory along the road facing the Seine river is on the left hand side. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 2, 1904, p. 1. Private collection.

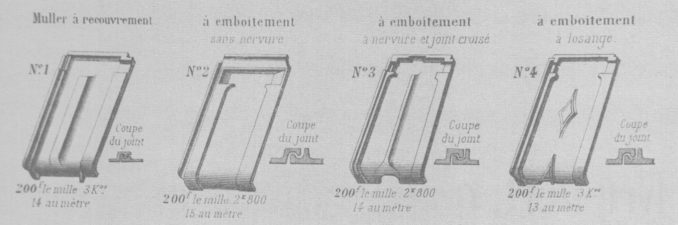

At the beginning the factory produces interlocking tiles using the process patented by the Gilardoni brothers, also from Altkirch.

Interlocking tiles. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

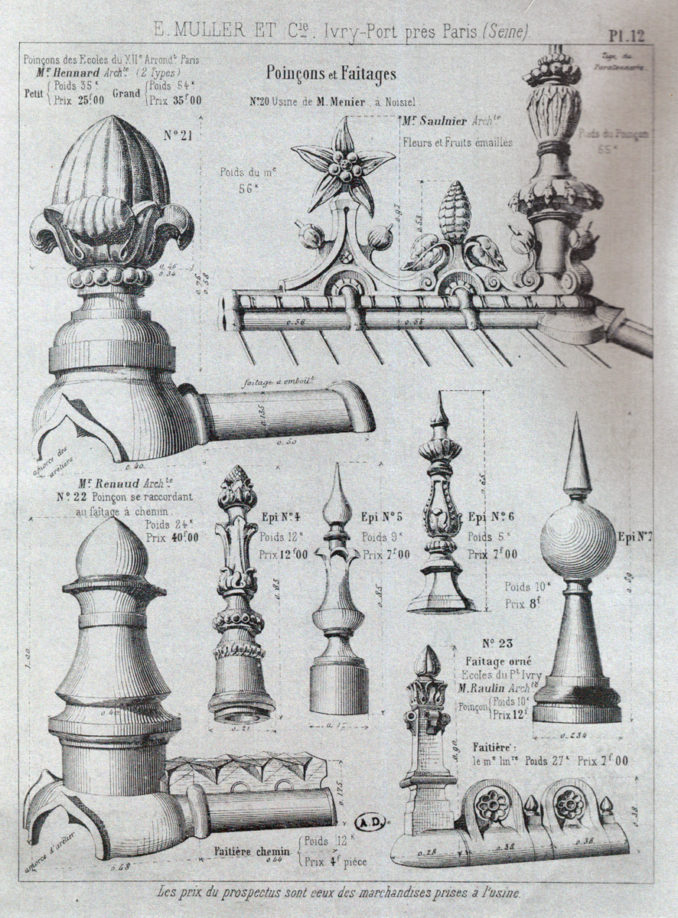

Roofing accessories are an important part of the production because they make it possible to customize a building. A number of special models are therefore created by several architects, which can then be edited.

-

Ridge models. Muller Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896, pl. 12. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

After starting the manufacture of enamelled products in 1866, the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry diversified its activities by producing raw and enamelled bricks and terracotta facade decorations, both raw and enamelled. Their composition allows them to be fired at high temperatures, making them waterproof.

Enamelled bricks Muller on an building entrance, Croix Faubin street, 10, in Paris. Photo by the author.

In 1871-1872, Muller provided his first large-scale architectural decoration for the Menier chocolate factory’s mill in Noisiel, the world’s first building with a load-bearing metal structure, designed by the architect Jules Saulnier.

Mill of the Menier chocolate factory at Noisiel Jules Saulnier architect, 1871. Photo internet.

Soon after, in 1875, the factory had 150 workers. Muller is of course present at the Universal Exhibitions, the one of 1867 and the one of 1878 where he ensures the success of architectural ceramics. At the 1889 Universal Exhibition, the domes of the Palais des Beaux-Arts and the Palais des Arts libéraux adorned with his turquoise-blue glazed tiles caused a sensation. He also presented glazed stoneware tiles for the first time.

Universal Exhibition of 1889, Palais des Beaux-Arts, architect Formigé, turquoise-blue glazed tile dome by Muller Photo National Gallery of Art, Washington.

For the first time, he also presented enamelled stoneware, including a copy of the Frieze of the Archers[2] from the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) brought back to the Louvre by the Delafoy expedition in 1885-1886. This frieze was later supplemented by a decoration of columns and flower boxes with lions for the winter garden of a private mansion in 1893, before being offered by catalogue and invoiced according to the number of archers requested.

Frieze of the archers, after the frieze of the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) of the Louvre museum. Vestibule of the building 11 rue des Sablons in Paris. Photo by the author.

It was at the end of the exhibition that Émile Muller died on November 11, 1889. His son Louis (1855-1921), known as Louis d’Émile, succeeded him as head of the company, whose name became “Émile Muller & Cie”. While keeping the production of enamelled bricks and mechanical tiles at the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry, Louis d’Émile Muller opens up now fields of operations for the factory.