Author: f.descouturelle

Hector Guimard’s participation in the 1925 Exhibition of Decorative Arts– Part 1

7 September 2025

We are taking advantage of the celebrations marking the centenary of the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, held in Paris in 1925[1], to publish our research on Hector Guimard’s participation in this event. The architect’s relatively modest contribution is somewhat reflective of his career in the aftermath of the First World War. This period has ultimately been little studied, but the 1925 Exhibition was one of its highlights and undoubtedly one of its most interesting moments. Guimard’s participation took the form of three works in one of the exhibition’s sections called the French Village: the town hall and two funerary monuments. While we have a comprehensive study of the French Village currently underway, we have chosen to highlight some lesser-known aspects, such as the interiors of the town hall and the cemetery. We will begin by discussing the context that led to the organization of the exposition, Guimard’s role, and his participation in the debate of ideas on the eve of this major event for the decorative arts and architecture.

Driven by Art Nouveau in the 1890s, the revival of European architecture and decorative arts that began in the late 19th century reached maturity around 1910, then continued into the 1920s with what would retroactively be called the Art Deco style, reaching a spectacular climax in France with the 1925 Exhibition. The long gestation period of this event—which began twenty years earlier and was postponed several times, notably due to the First World War—was commensurate with its success (more than 16 million visitors) and its international impact, propelling France to the forefront of nations in this field.

The organizers’ stated ambition was to exhibit only new and modern works[2], so no space was given to older styles, which were confined to exhibitions outside the event, such as the one organized at the Galliera Museum[3]. Even though some observers recognized the contribution of the 1900 artists to modern art, the break with Art Nouveau was already largely complete. Among a few famous statements, that of the painter Charles Dufresne (1876-1938) summed up the general mood of the time quite well: “The art of 1900 was the art of fantasy, that of 1925 is the art of reason” … With a few exceptions, critics were therefore fierce towards Art Nouveau, often dwelling on its excesses and quickly forgetting that the architecture and decorative arts celebrated with pomp and circumstance in 1925 drew in part from the renewal that had begun thirty years earlier. It would take a decade before interest in Art Nouveau was rekindled and its rehabilitation and protection began to be considered[4].

Official poster for the 1925 Exhibition Priv.coll.

In 1925, among the names of participants who took advantage of the event to launch or consolidate their careers, such as Mallet-Stevens, Le Corbusier, Roux-Spitz, and Patout, others were already active on the art scene in the 1900s. A sign of a certain recognition, the presence in 1925 of Plumet, Sauvage, Dufrène, Follot, and Jallot was also proof of their ability to adapt and renew themselves. Two of them, Maurice Dufrène (1876-1955) and Paul Follot (1877-1942), were even at the head of decoration workshops in Parisian department stores (La Maîtrise at Galeries Lafayette for the former, Pomone at Le Bon Marché for the latter). The success of the high-quality Art Nouveau productions of these two great names in decoration at the turn of the century did not prevent them from shifting towards a more stripped-down style in the mid-1900s and then, in the 1910s, towards compositions in which curves had almost disappeared.

Hector Guimard’s situation was somewhat different from that of his colleagues. Although he had evolved his style towards greater simplicity and sobriety, he always refused to give in to fashion. On the eve of the 1925 Exhibition, he told a newspaper: “Let’s just be ourselves, impose the discipline of harmony on ourselves, without believing that Fashion can and should dictate Art[5].” We will return to this principle a little later, as it was a guiding principle of the 1920s that largely explains the choices made by the architect during this period.

At the beginning of this new decade, Guimard continued to focus primarily on architectural work, as the loss of his studios in the aftermath of the world war had greatly reduced his work in the field of decorative arts. However, the activism he still displayed in the early 1920s allowed him to retain a certain influence within organizations known for promoting new ideas and heavily involved in the genesis of the 1925 Exhibition. Thus, even though he no longer held any responsibilities within the Société des Artistes Décorateurs (SAD)[6], he was still a member in the early 1920s and even exhibited there in 1923[7]. It should also be noted that during his trip to the United States in 1912, Guimard had been commissioned by the SAD. He introduced himself to the Americans as vice-president of the association and promoter of “The International Exhibition of Modern Architecture and Decoration,” which was to be held in Paris in 1915[8]…

It was therefore as an expert on the subject and spokesperson for modern ideas in the run-up to the exhibition that he became a founding member of the Groupe des Architectes Modernes (GAM)[9], holding the position of vice-president alongside Henri Sauvage (1873-1932), under the presidency of the indispensable Frantz Jourdain (1847-1935).

Letter from the Groupe des Architectes Modernes requesting the fee of 40 F from its members, dated 10 March 1928 and signed by Boileau. Coll. MOMA. All rights reserved

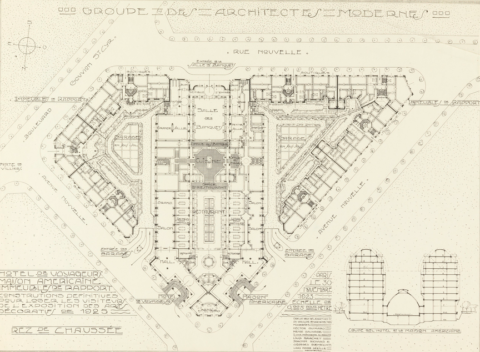

In the same interview in 1923, he justified its creation by the need to promote modern ideas that would undoubtedly be expressed during the upcoming event and, aware that the pavilions built would only have a short-lived existence, by the need to create an annex outside the 1925 Exhibition sponsored by the French State and the City of Paris “where modern architecture would be expressed, like jewelry, furniture, and fabrics, in definitive materials. These buildings would provide modern decorators with a living setting and industrialists with an initial outlet for their modern production, without which a reaction would be to be feared. Most of the pavilions built for the exhibition were indeed destroyed after the event, and this annex project never saw the light of day, nor did the ambitious project entitled “Travelers’ Hotel/American House/ Investment Buildings, permanent constructions for visitors to the 1925 Decorative Arts Exhibition,” which we know existed from three plans signed by several GAM architects, including Guimard, and which was to be located on Boulevard Gouvion-St-Cyr in Paris (75017).

Plan of the ground floor of the final building design by the Groupe des Architectes Modernes for the 1925 Exhibition, dated November 30, 1923. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved..

The GAM was ultimately entrusted with the creation of a section called the French Village within the exhibition. This could be seen as compensation, or even a way of keeping it at arm’s length, but the fact that several of its members were tasked with constructing some of the most important buildings at the event nevertheless confirms the association’s influence on the exhibition.

The French Village Town Hall

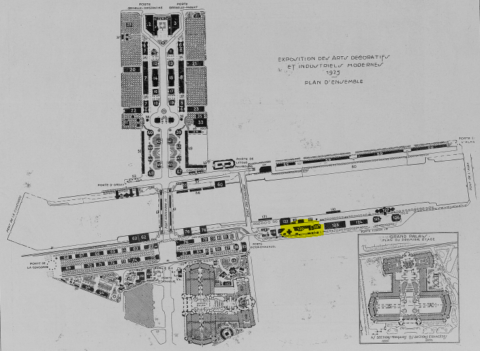

The French Village occupied a relatively small area around Cours Albert 1er, slightly away from the Esplanade des Invalides, which was considered the epicenter of the exhibition. Comprising some twenty buildings designed by as many architects from the GAM[10], the complex was a kind of architectural proposal intended to represent a village from the early 20th century.

Plan d’ensemble de l’Exposition de 1925 implantée de part et d’autre de la Seine. L’emplacement du French Village est surligné en jaune. La Construction Moderne, 03 Mai 1925. Coll. part.

In addition to the essential town hall, church, and school, there was an inn, a “bourgeois” residence, a community center, a bazaar[11], various commercial buildings, and several so-called secondary structures such as electrical transformers, a sanitary unit, and a wash house. Without exception, all these structures shared the common feature of having been built in a modern style.

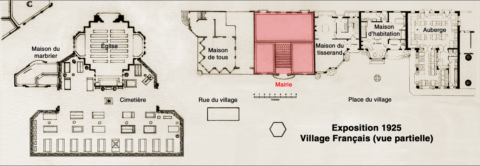

Partial plan of the French Village based on plans from the portfolio L’Architecture à l’Exposition des arts décoratifs modernes de 1925/Le Village moderne/Les Constructions régionalistes et quelques autres pavillons/Rassemblés par Pierre Selmersheim, published by Charles Moreau, 1926. Photomontage by F. D.

For economic reasons and due to constraints related to its environment, the ambition of the initial project had been scaled back. The architects had to work around existing plantings and connections to the sewer, water, gas, electricity, and telegraph systems. Furthermore, as the area ultimately allocated to the project did not allow for the construction of independent buildings, Dervaux had no choice but to make the buildings adjoined (with the notable exceptions of the church and the school). Most of them were therefore aligned lengthwise, parallel to the Seine. This revision of the initial project had the immediate effect of changing the name of the complex from “Modern Village” to “French Village,” as the GAM architects had been unable to demonstrate sufficient urban planning skills. It should be noted that this double name persisted, even during the exhibition, as some authors felt that the small village was modern enough to retain this description.

The Guimard town hall was one of the last buildings in the village to be completed (along with Pierre Patout’s (1879-1965) electrical transformer), even though the exhibition had been open for over a month[12]. Several old postcards show the building still under construction, despite the photographers’ efforts to hide it or relegate it to the background…

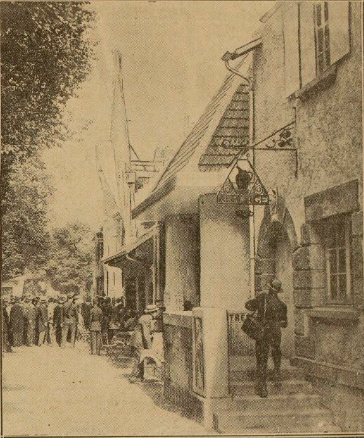

View of the French Village. In the background on the left, the town hall under scaffolding, as well as the Patout transformer on the right may be seen, ancient postcard. Private collection.

This delay in the construction of one of the main buildings in the small town probably explains its late inauguration. It was not until Monday, June 15, 1925, that the French Village was inaugurated, as shown in a photo in the Excelsior newspaper, in which the town hall appears to be free of scaffolding.

The inauguration of the French Village, Excelsior, 16 Juna, 1925 Bnf/ Gallica

With its back to the river, Guimard’s town hall stood at the edge of the village square, adjoining the” Maison de Tous” on its left, designed by the talented urban planner D. Alfred Agache (1875-1959), and the “Maison du Tisserand” by architect Émile Brunet (1872-1952) on its right. Agache perfectly summed up the spirit that guided the GAM in the construction of this complex: “(…) the “Village de France”, which we built in order to provide a snapshot of what a rural community should be, to meet the needs of modern life[13].”

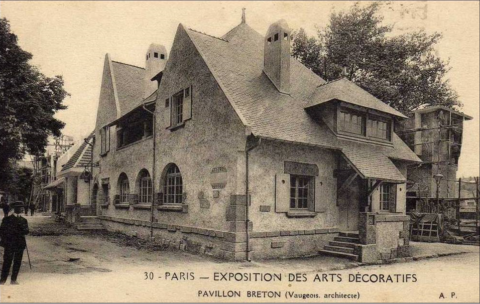

The townhall of the French Village, ancient postcard Private collection .

Recognizing that they had been unable to construct separate buildings, the two architects took advantage of this immediate proximity to create an opening allowing circulation between the two structures[14], no doubt believing that the functions and roles of the two buildings were compatible and complementary.

The “Maison de Tous” and the Town hall of the French Village, ancient postcard, private collection

The exterior appearance of the building is well known thanks to numerous old postcards on which it is either the main subject or a secondary subject, with the eleven pinnacles punctuating the roof often making it impossible to miss in photographs. The building appears to be a synthesis of Guimard’s last pre-war works and his research in the early 1920s to develop an economical construction method called “Standard-Construction”, which was used to build the small hotel on Square Jasmin in the 16th arrondissement of Paris.

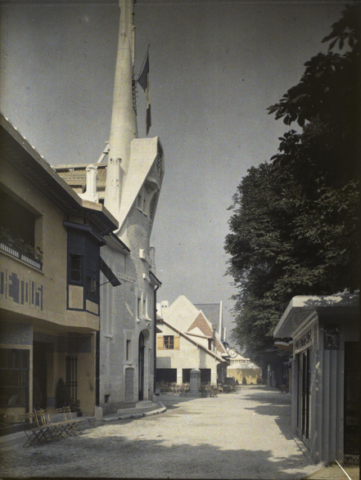

Adding a touch of originality to the group of buildings, the highest of these pinnacles rose directly above the central bay of the slightly curved main facade, punctuated by numerous openings, but set back from a cement canopy covering the clock. Like a signal, both in terms of its height and its function as a carillon, it symbolically rivaled the bell tower of the neighboring church built by architect Jacques Droz (1882-1955) and reminded visitors of the importance of republican life in a modern village… We also have a fairly accurate idea of its colors, as the Archives de la Planète at the Albert-Kahn departmental museum hold numerous autochromes of the event, in which the town hall appears in light tones due to its asbestos brick and white and gray stone cladding[15].

View of the French village. On the left, the Maison de Tous and the town hall, followed by the village square and then the inn; on the right, the fish market, autochrome. Albert Kahn Departmental Museum, Hauts-de-Seine Department

Two other sources are invaluable for learning about the town hall: the portfolio published by Pierre Selmersheim[16] and Anthony Goissaud’s article in La Construction Moderne[17]. A third unpublished article in Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux[18] still eludes us, but we hope that this publication will enable us to find it…

Main facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 2, 1926. Private collection.

A postcard published for promotional purposes by Guimard (used to illustrate the header of this article) completed this editorial material. On the front is an illustration by artist A. C. Webb (1888-1975)[19]. The back comes in different versions depending on the intended use (advertising with a list of town hall employees, promotional material touting a construction technique, or blank for correspondence, etc.).

Rear facade of the town hall, portfolio Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and Several Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim, Charles Moreau Publishing, pl. 3, 1926. Private collection

The panels framing the main entrance door, intended for municipal notices, were used here to showcase the companies and artists who collaborated on the town hall project. Among them were some more or less famous names, such as the Schenck family of ironworkers, who made the wrought iron staircase railing, the stained-glass artist Gaëtan Jeannin, who created the stained-glass windows in the wedding hall, and the painter René Ligeron, whom we will discuss later.

Finally, a collection of cast iron pieces from Guimard’s repertoire of models, produced since 1908 by the Saint-Dizier foundry, adorned the building, particularly on the rear facade, where there were balconies on the first floor and panels decorating the windows on the ground floor.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Library of Decorative Arts. Gift of Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

At the ends of the two facades, the downspouts from the Saint-Dizier foundry connected to gutters from the Bigot-Renaux foundry. These undecorated gutters were fitted with “outward-angled gutter ornaments” also from the Saint-Dizier foundry, which appear to have been used only here.

Details of the rear facade of the town hall decorated with cast iron. Decorative Arts Library, donated by Adeline Oppenheim-Guimard, 1948. Photo by Laurent Sully Jaulmes.

Fixed decoration

Among the companies that played an important role in the interior decoration of the building was ELO[20], whose fiber cement paneling covered part of the interior walls. This company experienced significant growth in the 1920s, when there was high demand for inexpensive decorative elements in all styles. As cost savings were a common denominator in most of Guimard’s buildings, it is not surprising that he called on this company for the town hall, given that the budget was particularly limited[21]. ELO paneling thus joined the long list of new materials (and sometimes new techniques) used by the architect throughout his career. The possibility of modeling them to his style was an additional advantage. Notable examples include the use of Lantillon fiberboard panels covering the ceilings of Castel Béranger, Castel Henriette, Villa Berthe, and the Lantillon pavilion in Sevran, as well as Garchey glass stone, also used at Castel Henriette, and ferrolithe, used on the rear façade of the Pavillon de l’Habitation in 1903 [22].

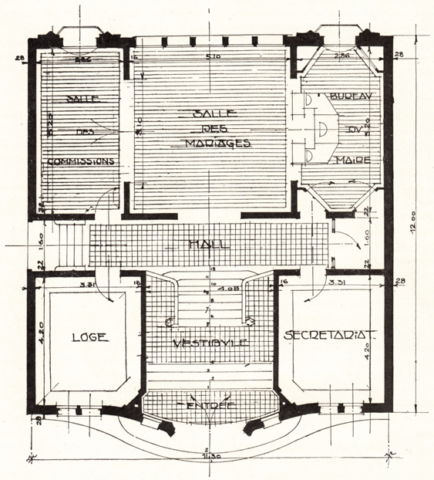

Plan of the town hall published in La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

An exhibition devoted to the new materials and techniques used in the construction of the town hall occupied the large room on the ground floor, accessible only through two doors at the rear. Among those featured were Taté for plaster, stone, and marble; Lambert Frères for asbestos bricks; and the Société de Traitement Industriel des Résidus Urbains (Industrial Urban Waste Treatment Company)[23].

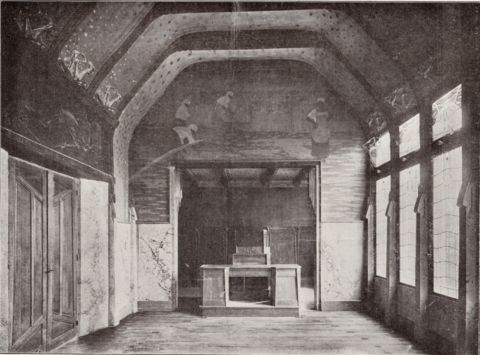

In the photo from La Construction Moderne, we can see ELO paneling covering part of the wall behind the mayor’s desk.

Wedding hall with the mayor’s desk in the background and Jeanneau stained glass windows on the right. La Construction moderne, November 8, 1925. Private collection.

Public collections, meanwhile, hold another photograph that allows us to appreciate the wood paneling sculpture in the foreground.

Wedding hall and the mayor’s desk. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserveds.

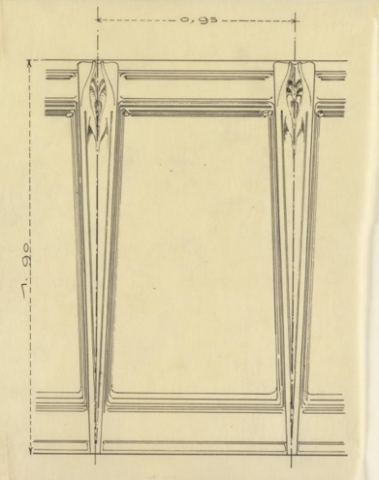

Finally, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum holds the original and almost definitive design for the paneling. A subtle and delicate blend of the organic and plant worlds, the main motif takes us back twenty years, bringing a touch of sentiment dear to Guimard and open to interpretation.

Drawing of the town hall paneling. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. All rights reserved.

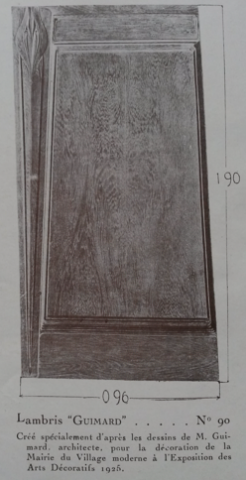

This paneling would appear under the name “Lambris Guimard” in the following year’s ELO catalogs. This was probably the architect’s last attempt to market a model commercially.

« Lambris Guimard », catalogue of the ELO company, 1926. Coll. part.

ELO is also likely the maker of the striking bas-relief featuring vultures above the doors to the wedding hall, signed by Raymond Andrieux. Although birds of prey—alongside wild animals—were among the favorite subjects of artists of the time, one might wonder why they were chosen to adorn the wedding hall.

Detail of the frieze depicting vultures by R. Andrieux decorating the wedding hall. GrandPalaisRmnPhoto. All rights reserved.

Although Guimard undoubtedly met this virtually unknown artist through the ELO company—or perhaps it was the other way around—he may have wanted to seize the opportunity to promote a young artist while adapting an existing work at minimal cost. Information about Raymond Andrieux is very scarce[24], but we have found a trace of a work, now in a private collection, whose resemblance to the bas-relief at the Town Hall is particularly striking.

ELO panel with vultures signed R. Andrieux on the lower right and bearing the ELO company stamp on the reverse, width 1.37 m, height 1.15 m, depth 0.18 m. Private collection.

Our investigation led us to the 1924 Salon des Artistes Français, where Andrieux exhibited a panel in the Decorative Arts category under the caption: “Vultures, fiber cement panel”[25]. This work therefore certainly served as a model for the bas-relief in the wedding hall, with Guimard probably asking the young artist to draw inspiration from his 1924 work and adapt it into a frieze. It is even possible that this work appeared in the manufacturer’s catalog, but the copies we have do not mention it.

Among the other artists who collaborated on the interior decoration of the building was René Ligeron (1880-1939)[26], whose two paintings depicting scenes of the French countryside—a decorative theme found in many town halls—adorned the walls of the gables of the wedding hall. Thanks to the previous photos, we were familiar with the painting entitled Harvesters binding sheaves. A third, previously unseen view of the wedding hall being decorated gives a glimpse of the second work, entitled Woman guarding sheep, in the same rural style as the first.

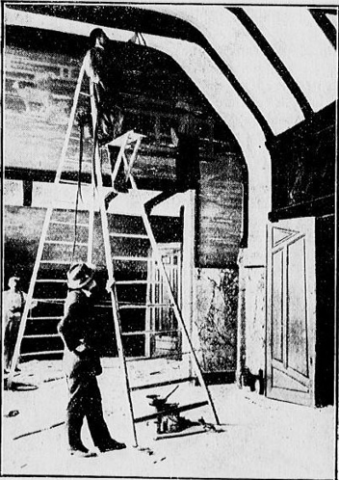

The wedding hall of the town hall of the French Village under decoration Recherches et Inventions n° 163, mars 1928. Private collection

It is not impossible that the figure in profile with a gray beard, wearing a hat and standing on a ladder, is Hector Guimard himself, who came to supervise the work…

(to be continued)

Olivier Pons

[1] The event took place from April 28 to November 8, 1925. For convenience, we will refer to it as the 1925 Exhibition or simply the Exhibition.

[2] The rules stipulated: “(…) works of new inspiration and genuine originality, executed and presented by artists, craftsmen, industrialists, designers, and publishers, and falling within the scope of industrial and modern decorative arts, are eligible for admission to the Exhibition. Copies, imitations, and counterfeits of ancient styles are strictly excluded.” Exhibition rules. Private collection.

[3] “Exhibition of the Renovators of Applied Art from 1890 to 1910,” Galliera Museum (Paris), June 6 to October 20, 1925.

[4] See the article by Léna Lefranc-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/proteger-le-patrimoine-art-nouveau-parisien-initiatives-et-reseaux-dans-lentre-deux-guerres/

[5] Interview given to L’Information financière, économique et politique, February 19, 1923. BnF / Gallica.

[6] The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of Decorative Artists) was founded in 1901 on the initiative of lawyer René Guilleré and several other leading figures in the decorative arts. Its aim was to “promote the development of the decorative arts,” as stated in Article 2 of the SAD’s statutes, “approved by order of the Prefect of Police on April 6, 1901.” Private collection.

[7] The catalog failed to mention his name, but his participation in the 1923 SAD is confirmed by several articles. For example, the January 1923 issue of L’amour de l’Art mentions the three tombs presented by Guimard, including “that of the Henri family,” a unique monument that undoubtedly still exists and which we are actively searching for…

[8] See the article: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/le-premier-voyage-dhector-guimard-aux-etats-unis-new-york-1912/

[9] See the article by Léna Lefran-Cervo: https://www.lecercleguimard.fr/fr/entre-norme-et-liberte-larchitecture-du-point-de-la-vue-de-la-societe-des-architectes-modernes/

[10] It was built under the direction of architects Charles Genuys (1852–1928) and Gouverneur, based on an overall plan designed by Adolphe Dervaux (1871–1945). See Lefranc-Cervo, Léna, Le Village français: une proposition rationaliste du Groupe des Architectes Modernes pour l’Exposition Internationale des arts décoratifs de 1925, research thesis (2nd year of 2nd cycle) supervised by Alice Thomine Berrada, École du Louvre, September 2016.

[11] The bazaar was built based on plans by architect Marcel Oudin (1882-1936) for the Magasins Réunis chain. A specialist in reinforced concrete construction, Oudin had become one of the architects of the Corbin family from Nancy, owners of the Magasins Réunis in eastern France, but also in Paris (Magasins Réunis République, À l’Économie Ménagère, Grand Bazar de la rue de Rennes).

[12] In an original photo dated June 1, 1925, the town hall still appears to be covered in scaffolding.

[13] La Cinématographie française, April 11, 1925. La Maison de Tous, which was initially to be called Maison du Peuple (House of the People) – a name considered too connotative – was undoubtedly one of the most attractive buildings in the Village, both in terms of its architectural design and the ideas behind its conception and deserves a full article.

[14] Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires, June 17, 1925.

[15] An article devoted to Guimard’s use of bricks is in preparation and will provide a more complete overview of the materials used in the French Village town hall.

[16] Architecture at the 1925 Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts/The Modern Village/Regionalist Buildings and a Few Other Pavilions/Compiled by Pierre Selmersheim. Charles Moreau Editions, 1926.

[17] “The Town Hall of the French Village,” A. Goissaud, La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[18] “La Mairie du Village français à l’Exposition,” Le Moniteur des Architectes communaux, 1925, no. 2.

[19] Alonzo C. Webb (1888-1975) was an American painter and engraver who spent his life between the United States and Europe. After studying architecture and fine arts first in Chicago and then in New York, he moved to Europe after World War I and settled in France in the 1920s, where he produced drawings of ancient monuments and landscapes for advertising and to illustrate articles in major national newspapers (including L’Illustration). Guimard may have met him through his wife Adeline, as Webb was part of the small American colony in Paris. After specializing in engraving, he moved to London in the late 1930s, where he died in 1975.

[20] Founded in 1902, ELO had its headquarters and factories in Poissy (Yvelines) and showrooms located at 9 rue Chaptal in Paris’s 10th arrondissement. It offered decorative paneling and fiber cement (a mixture of asbestos and cement) cladding for both interior and exterior use, thanks to its strength, rot resistance, and fire resistance. Manufactured in large quantities, the cladding was designed to imitate wood, bronze, stone, leather, and even ceramic at prices well below those of these materials (Journal Excelsior, May 6, 1925).

[21] The budget allocated to the town hall was 92,000 francs. La Construction Moderne, November 8, 1925.

[22] Ferrolithe was a type of coating that imitated stone. Highly resistant and moisture-proof, it was mainly used to renovate and cover exterior walls.

[23] L’Architecture no. 23, December 10, 1925.

[24] Raymond Andrieux was an artist from Lille who became a member of the Société nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1926 in the sculpture category. A trinket tray decorated with a vulture and signed by R. Andrieux was sold at auction in 2016.

[25] Le Grand Écho du Nord de la France, May 21, 1924. BnF/Gallica.

[26] (Jacques) René Ligeron was born in Paris on May 30, 1880, and probably died in Algiers on December 8, 1939. A traveling painter, he was best known for his engravings, with a preference for etchings. A student of Lepeltier, Lefebvre, and Robert-Fleury, he exhibited mainly landscapes and a few portraits at the Salon des Artistes Français from 1905 onwards. In 1936, the press reported on an exhibition in a Parisian gallery showcasing his latest works, notably blackened wooden panels intended to decorate a large dining room, one fragment of which, featuring Japanese-inspired decoration, has recently been rediscovered.

The « Maison Moderne » of Julius Meier-Graefe — Part 2

7 July 2025

Organization, offerings, and operation of La Maison Moderne

Among all the artists selected, two Belgian compatriots were given the most important assignment: Georges Lemmen, first and foremost. Meier-Graefe entrusted him with the task of designing the most recognizable element of the brand: its logo. This symbol, intended to be the “brand” of La Maison Moderne, consisted simply of the initial letters of the gallery’s name superimposed on each other, drawn in curves in line with the style already used by Lemmen in the posters for Dekorative Kunst. Simple in design, this logo appeared on most of La Maison Moderne’s production and publications, in its original or a more elaborate form.

Georges Lemmen, logo of La Maison Moderne, 1899.

The design of La Maison Moderne was commissioned to the artist Meier-Graefe trusted most: Henry Van de Velde. He designed a storefront with display windows, allowing passersby to see a selection of the items sold inside.

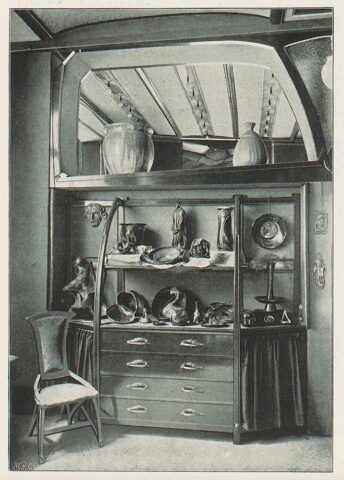

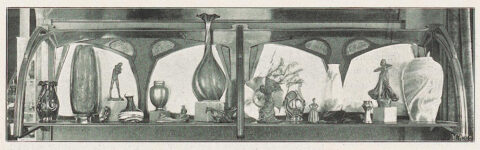

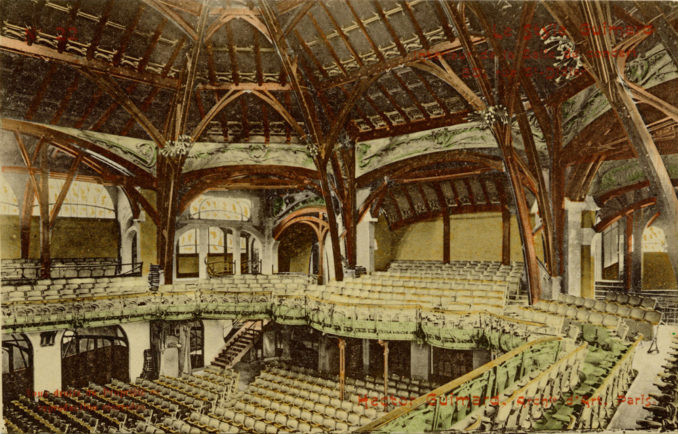

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. On the shelf of the display cabinet are two vases by Dufrène and Dalpayrat.

Maurice Dufrène, designer, Dalpayrat and Lesbros, ceramist, flamed stoneware, c. 1899, purchased by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs at La Maison Moderne in 1899, silver mount by Cardeilhac added in 1900, exhibited at the UCAD pavilion at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1900, Musée des Arts Décoratifs. All rights reserved.

The typography for the letters was designed by Georges Lemmen[2]. This choice reflects Meier-Graefe’s confidence in the talent of the two Belgian artists, as the shop front played as important a role as a poster for shops at the end of the 19th century. In the gallery, Van de Velde proposed a complete decor, alternating display cases, shelves, and furnished rooms.

The other artists selected to appear in the gallery catalog were countless: more than sixty were listed. Despite Meier-Graefe’s stated desire to create a gallery that favored French works, foreign artists were very numerous within its walls.

Bernhard Hoetger (Hörde, Germany, 1874 – Beatenberg, Switzerland, 1949), The Storm, c. 1901, bronze, Musée d’Orsay, RF 4189, height 0.311 m, width 0.245 m, depth 0.25 m. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, bronze 3322-1, La Sculpture p. 5.

To provide an overview of the diversity of the offerings, it is worth mentioning all the nationalities represented among La Maison Moderne’s collaborators: French, Belgian, German, Italian, Austrian, Hungarian, Romanian, Serbian, Danish, Dutch, and Finnish. It is interesting to note the absence of British and Spanish artists among them. Meier-Graefe’s taste is the only real common denominator among all these artists, and they were selected with a concern for consistency that was dear to him (Bing had been criticized for a lack of consistency four years earlier).

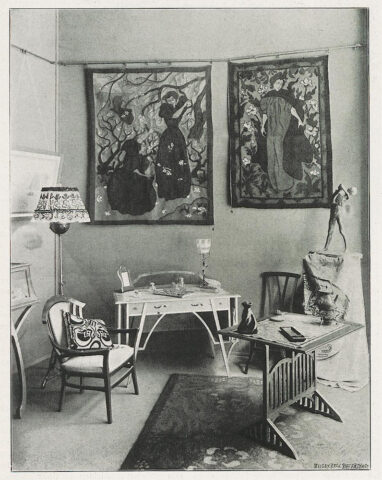

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The establishment also offered a wide range of products: the article announcing its opening in September 1899 stated that “The galleries of the ‘Maison Moderne’ will contain a little bit of everything: furniture, upholstery fabrics, carpets, ceramics, glassware, lighting fixtures, embroidery, lace, jewelry, fans, toiletries, and fancy items—from brushes to cane knobs—in short, everything for the home and the person[3].” This prediction was clearly confirmed: La Maison Moderne offered everything needed to furnish an interior and all the accessories—except clothing—that a wealthy person in the early 20th century might need. The same article also mentions a selection of master painters whose works were offered for sale: Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Paul Cézanne, Auguste Renoir, Maurice Denis, Théo Van Rysselberghe, Édouard Vuillard, and Pierre Bonnard. However, this article remains the only mention of the painting exhibition at La Maison Moderne. We do not know which paintings were exhibited there, and no other artists can be identified.

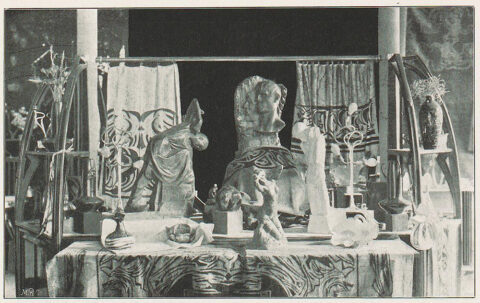

In addition to offering individual items for sale, the gallery also designed and furnished rooms, apartments, and other types of interiors. Most of these complete designs were carried out under the direction of Abel Landry, Pierre Selmershein, or Maurice Dufrène. No examples have survived other than old photographs, such as those of this fashion store, also designed by Van de Velde for the Palast Hotel on Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, managed by P. H. C. Kons.

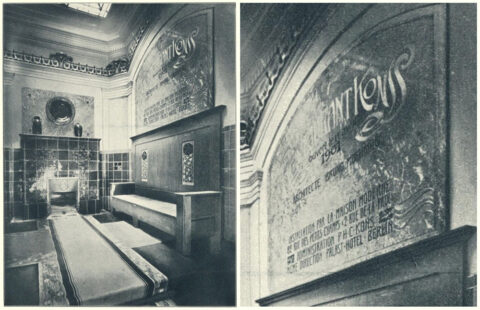

Henri Van de Velde, interior design of a fashion store “filiale de Madame Henriette” in the Palast Hotel in Berlin, realized by La Maison Moderne with furniture designed by Abel Landry, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

The most important and best documented order was for the interior design of the German restaurant Konss[4], located in Paris on the corner of Rue Grammont and Boulevard des Italiens, on the first floor, also for P. H. C. Kons. The architect appointed by the owner to oversee the work was Bruno Möhring[5]. He decided on the overall layout of the place, and Kons renewed his trust in La Maison Moderne for the design and installation of the decorations. The work took place from January 15 to April 17, 1901. A real success, La Maison Moderne’s participation in the design was noted in the entrance hall of its establishment. A few months later, Meier-Graefe reported on it in L’Art Décoratif, under one of his pseudonyms: G. M. Jacques[6]. Reading this article, it is striking that, having signed it with a French-sounding pseudonym in his French magazine, Meier-Graefe adopts a point of view that could be that of a Parisian journalist, criticizing Möhring’s design by claiming that his “Latin instincts are closed to his Germanic conception.” “when it was in fact his own company that carried out the development. By sticking to what he imagined to be a ”Latin” mindset, he no doubt wanted to avoid any suspicion of a conflict of interest.

Bruno Möhring, landing on the staircase of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, ceramics by Laüger, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 88, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, green dining room of the Konss restaurant, first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, panels by Georges de Feure, Architektonische Monatshefte, VII. Jahrgang 1901, pl. 87, Leipzig/Vienna, Friedrich Wolfrum, 1901, online library of the University of Stuttgart.

Bruno Möhring, lilac dining room of the Konss restaurant, on the first floor of 30 rue de Grammont in Paris, 1901, executed by La Maison Moderne, L’Art Décoratif, November 1901, article by G. M. Jacques (Julius Meier-Graefe). Online library of the University of Heidelberg.

La Maison Moderne’s operating model is very well thought out, reflecting its director’s careful consideration and innovative abilities. Aware of the behavior of French collectors, who treat art objects in the same way as paintings or sculptures, Meier-Graefe proposed an organization inspired by the Vereinigten Werkstätten für Kunst im Handwerk (United Workshops for Art and Craft) in Munich. While French decorative art remained primarily a commissioned art form, in which artists responded only to specific requests by creating unique models that could not be reproduced, Meier-Graefe proposed the opposite system: objects were no longer commissioned by individuals but were mass-produced by artists and craftsmen. However, production remained in the realm of craftsmanship and did not shift to industry. In the absence of administrative archives from the gallery, no precise figures can be given: the number of pieces produced for the same model must have been relatively small, but there were no unique works. Without even mentioning taste or style, it was first and foremost the way of thinking that the director of La Maison Moderne wanted to change.

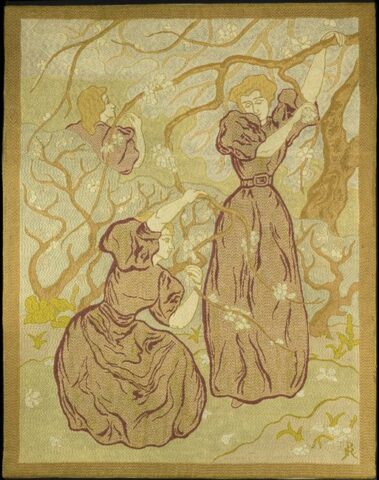

There were exceptions to this system. Tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson, handmade by his wife France Ranson-Rousseau in single copies, were offered for sale at La Maison Moderne[7].

Paul-Élie Ranson, Printemps (Spring), wool tapestry on canvas executed by France Ranson-Rousseau, 1895, height 1.67 m, width 1.32 m, Musée d’Orsay, OAO 1788, rights reserved.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris. On the wall, two tapestries by Paul-Élie Ranson: Printemps and Femme en rouge, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Exhibition Femmes chez les nabis. De fil en aiguille (Women among the Nabis. From thread to needle) at the Pont-Aven Museum (June 22 to November 3, 2024), evoking the room in La Maison Moderne where Ranson’s tapestries were displayed. Photo by Bertrand Mothes.

However, these objects were made before the gallery opened and therefore do not fall under the manufacturing method developed by Meier-Graefe. The principle is simple: artists create designs and grant production rights to the gallery, which is responsible for executing them. The artist receives a portion of the sale price—defined by mutual agreement—for each object sold[8]. The possibility of producing multiple copies also allows Meier-Graefe to sell his objects at a “reasonable price,” in his own words. The “reasonable price” encourages purchases and provides the artist with a comfortable income. Here, “reasonable” should not be confused with “low.” While the prices of the objects sold at La Maison moderne did not reach those seen at Bing, they were nonetheless accessible to fairly well-off individuals, rather than workers or low-paid employees.

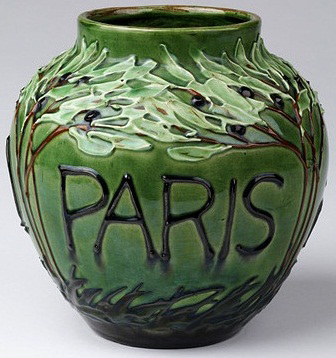

The gallery had its own workshops for the production of objects. The only one that can be confirmed with certainty is the leather workshop[9], but it is possible that there were also workshops for cabinetmaking, tapestry, brasswork, jewelry, and watchmaking. The fire arts, which were difficult to set up on a large scale in the heart of the Parisian capital, came from manufacturers associated with La Maison Moderne. The vase Exposition 1900 Paris, from Germany, is a good example. Manufactured by Tonwerke in Kandern, run by Max Laüger, it is not part of the factory’s usual production but was made exclusively for LMM, as evidenced by the gallery mark incised under its base alongside Laüger’s monogram and the factory mark.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, produced by La Maison Moderne, height 0.212 m, London, Victoria & Albert Museum. All rights reserved.

Max Laüger, Tonwerke workshop, Vase Exhibition 1900 Paris, circa 1900, painted earthenware under glaze, height 0.212 m, Paris, Musée d’Orsay. All rights reserved.

This approach to production and sales was complemented by a decisive choice of location for the gallery. 82 Rue des Petit-Champs is located just a few meters from Rue de la Paix, which remains one of the most prestigious shopping districts in Paris. In addition to being central, this location was frequented by a wealthy clientele receptive to artistic innovation. The street has since changed its name to Rue Danielle-Casanova. The former number 82 now corresponds to the current number 26, which is now occupied by a café.

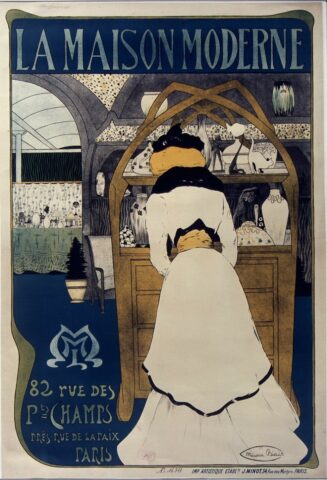

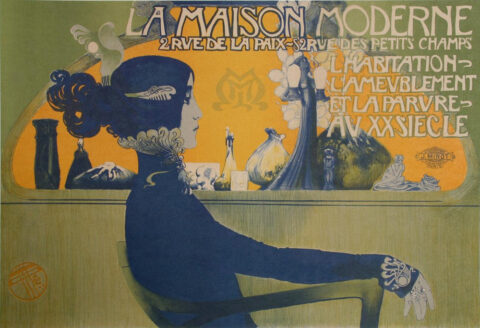

As the director of a commercial establishment, Meier-Graefe naturally used all the means available to him at the time to promote his gallery. Two posters were the cornerstone of his advertising campaign. The first was designed by Maurice Biais. It depicts an elegant lady looking at objects displayed in one of the shop windows designed by Van de Velde, faithfully reproduced.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg.

Maurice Biais, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1899–1900, color lithograph on paper, height 114 cm, width 0.785 cm, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

The objects depicted on the poster are all the more easily recognizable as Maurice Biais used photographs that would later be incorporated in the La Maison Moderne catalog. Among other items, the poster features a flamed enamel inkwell by Jakob Rapoport designed by Maurice Dufrène, small bronze sculptures by Georges Minne, a porcelain cat from the Danish manufacturer Bing & Grøndahl, and a lamp by Dufrène.

Maurice Dufrène, electric lamp, patinated bronze, no. 1580-1, height 0.55 m, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, Lighting fixtures, p. 9. Private collection.

Interior design of La Maison Moderne by Van de Velde, 82 rue des Petits-Champs in Paris, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, October 1900, online library of the University of Heidelberg. To the left of the display case, Le Petit Blessé by Georges Minne.

Georges Minne, Le Petit Blessé, bronze, height 0.25 m, Nationalgalerie, Berlin. All rights reserved. This sculpture is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, bronze no. 308-1, p. 21.

The second poster is the work of Manuel Orazi (fig. 5). With a composition and atmosphere completely different from that of Biais, it also features objects that were sold there. We can recognize an inkwell bearing a bronze figure by Alexandre Charpentier on a base designed by Dufrène and made of flamed stoneware by Adrien Dalpayrat, an armchair by Van de Velde, a bronze lamp by Gustave Gurschner, a vase by Dufrène and Dalpayrat, and a monkey figurine by Joseph Mendes da Costa. The distinctive feature of this poster is obviously the large, hieratic female figure that adorns it. This is in fact the famous dancer Cléo de Mérode, who lent her image to the gallery as its muse[10].

Manuel Orazi, J. Minot printing house, poster for La Maison Moderne, 1901, color lithograph on paper, height 0.83 m, width 1.175 m, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Gustav Gurschner, electric lamp, bronze, no. 718-1, height 0.48 m including lamps, Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (catalogue of La Maison Moderne), 1901, La Sculpture, p. 13. Private collection.

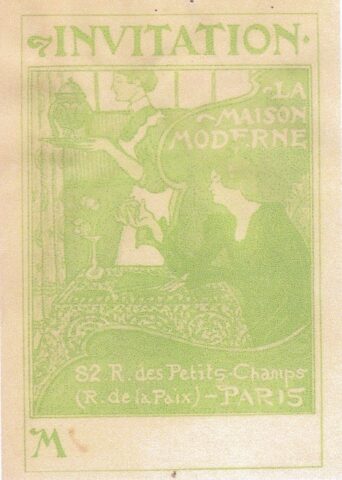

In addition to these posters, Meier-Graefe also published small leaflets designed to promote his gallery. The invitation card for the opening was designed by Georges Lemmen.

Georges Lemmen, invitation card to the inauguration of La Maison Moderne, 1899, color print on paper, height 0.19 m, width 0.13 m. Private collection.

The composition was also used as an advertisement in the pages of L’Art Décoratif. The two women depicted are not anonymous, as they are actually Mrs. Meier-Graefe and Jenny, a young servant.

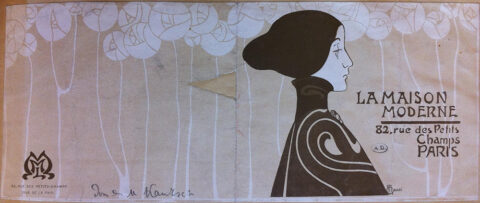

The second print was created by Manuel Orazi, who drew inspiration from his own poster for the design.

Manuel Orazi, brochure for La Maison Moderne, circa 1903, lithograph on paper, height 0.117 m, width 0.277 m, Paris, Bibliothèque des Arts Décoratifs.

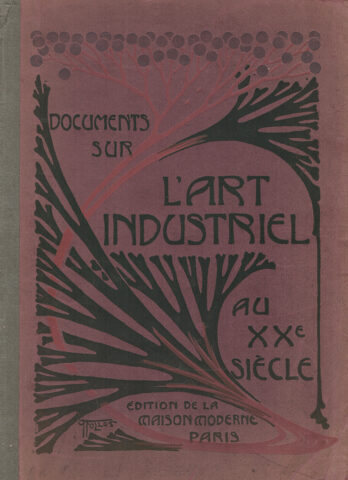

Meier-Graefe also printed discount coupons from the same poster, either for his best customers or to attract new ones. One of his most important advertising tools remained the book Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century), published in 1901.

Paul Follot, Cover of Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, height 0.30 m, width 0.208 m. Private collection.

Presented as a collection of the most beautiful works of art of the period, it is in fact the gallery’s commercial catalog, containing many references to objects from La Maison Moderne.

Félix Aubert, Maison Georges Robert, Iris fan no. 54-V and its box, c. 1900, polychrome silk lace, horn, emerald, pearl, height 0.28 m, diameter 0.48 m, Caen, Musée de Normandie. All rights reserved. This fan is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, La Dentelle, p. 4.

In addition to these independent advertisements, Meier-Graefe filled the magazines he edited with constant references to his gallery and collaborating artists. He also participated in events such as the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts in Turin in 1902, for which he published a postcard featuring real objects from his shop.

Maurice Biais, Société Éditrice Cartoline, Main hall of “La Maison Moderne” at the Turin Exhibition, 1902, vintage postcard, Miami, The Wolfsonian-Florida International University. All rights reserved.

However, despite all its innovative ideas and pioneering role at the beginning of the 20th century, the gallery was a failure. Its director sold it in 1904 to Delrue et Cie, who took charge of liquidating the stock[12]. The climate of xenophobia in Paris was detrimental to both Meier-Graefe and Bing, as French collectors resented a German coming to lecture them on what their taste should be[13]. Furthermore, although its structure was ingenious, production costs remained too high for the gallery to remain viable.

Abel Landry, armchair n° 43, produced by La Maison Moderne, mahogany, modern upholstery, height 1.04 m, width 0.75 m, depth 0.90 m, Zéhil gallery, Monaco. Photo: Zéhil gallery. This armchair is reproduced in Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, 1901, Furniture and decoration, p. 16.

This gallery, led by an innovative director with impeccable taste, never managed to find its audience, but remains the only real attempt in 1900 to create an alliance between art, industry, and commerce.

Bertrand Mothes

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[2] Cat. Exp Georges Lemmen 1865-1916, Brussels, Crédit Communal, Ghent, Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, Antwerp, Pandora, 1997, p. 58.

[3] R. [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], “Chronique de l’art décoratif, La ‘Maison Moderne’,” L’Art Décoratif, September 1899, no. 12, p. 277.

[4] It is likely that the doubling of the final “s” in the restaurant owner’s name was intended to make it sound German and avoid confusion with a French word that was a little too similar.

[5] In 1900, Möhring had already built the Restaurant allemand at the Universal Exhibition in Paris, which was a great success.

[6] G. M. JACQUES, “Un restaurant allemand à Paris,” L’Art décoratif, November 1901, no. 38, pp. 54-60.

[7] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle. Photographic reproductions of the main works of the contributors to La Maison Moderne. Commented by R. [Raoul] AUBRY, H. [Henri] FRANTZ, G.-M. JACQUES [pseudonym Julius MEIER-GRAEFE], G. [Gustave] KAHN, J. [Julius] MEIER-GRAEFE, Gabriel MOUREY, Y. [Yvanhoé] RAMBOSSON, E. [Émile] SEDEYN, Gustave SOULIER, G. [Georges] BANS, with nine additional illustrations by Félix VALLOTTON Les Métiers d’Art. Paris, Édition de La Maison Moderne, 1901, L’Ameublement, p. 36.

[8] R., op. cit. in note 3, p. 277.

[9] Documents sur l’Art Industriel au vingtième siècle, op. cit. in note 7, La Maroquinerie, p. II.

[10] Alexandre Charpentier (1856-1909).Naturalisme et Art Nouveau, exhibition catalog, Paris, Musée d’Orsay, N. Chaudun, 2007, p. 126.

[11] Roger CARDON, Georges Lemmen (1865-1916), Antwerp, Petraco-Pandora, 1990, p. 449.

[12] Advertisement for La Maison Moderne, Delrue et Cie, Fermes et Châteaux, November 1905, no. 3, p. IX.

[13] Nancy J. TROY, Modernism and the Decorative Arts in France: Art Nouveau to Le Corbusier, New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1991, p. 47.

List of artists mentioned in the Documents sur l’Art Industriel au XXème siècle (Documents on Industrial Art in the Twentieth Century)

Félix AUBERT

Henri BANS

Gyula BETLEN

Maurice BIAIS

Alexandre BIGOT

[manufacture] BING & GROENDAHLSofie BURGER HARTMANN

Alexandre CHARPENTIER

Cristallerie de Pantin

Jens DAHL-JENSEN

Pierre Adrien DALPAYRAT

Eugène DELATRE

Maurice DUFRÈNE

Paul FOLLOT

Édouard FORTINY

Maurin GAUTHIER

Gustave GURSCHNER

Bernhard HOETGER

Henry JOLLY

Emil KIEMLEN

G. KISS

Abel LANDRY

Georges LEMMEN

Hans Stoltenberg LERCHE

Clément MÈRE

Charles MILÈS

Georges MINNE

Koloman MOSER

Gabriel OLIVIER

Manuel ORAZI

Blanche ORY-ROBIN

Paul-Élie RANSON

Jakab RAPOPORT

Auguste RODIN

SAINT-YVES SCHLESINGER

Elisabeth SCHMIDT-PECHT

Tony SELMERSHEIM

Louis Comfort TIFFANY

Henry VAN DE VELDE

Heinrich VOGLER

Félix VOULOT

François WALDRAFF

To quote this article:

Bertrand MOTHES, “La Maison Moderne de Julius Meier-Graefe” in Catherine Méneux, Emmanuel Pernoud, and Pierre Wat (eds.), Proceedings of the Study Day Actualité de la recherche en XIXesiècle, Master 1, Years 2012 and 2013, Paris, HiCSA website, published online in January 2014.

What color were the red signaling glasses on Guimard’s metro surrounds?

( Note: in this article, the term “signaling glass” is used to translate the French “verrine”, meaning the protective cover of the lamp in a Guimard Metro candelabra)

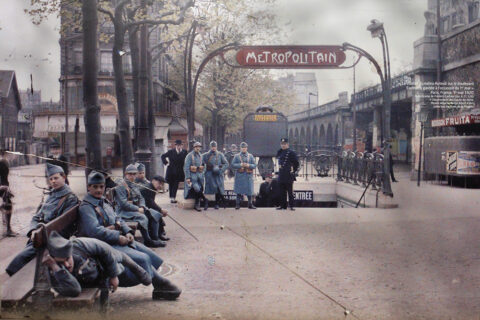

Due to the flow of contradictory information, we are being urged from all sides to give our opinion on this crucial point. We are happy to oblige, all the more so as we had neglected to add any nuances to the overly clear-cut opinion, we expressed in the two books published in 2003 and 2012 that established a serious study of Guimard’s metro [1]. The recent discovery of a color photograph taken in the 1960s is a fitting conclusion to our article.

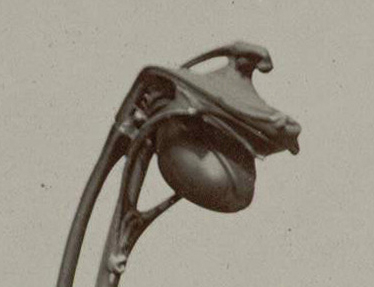

To define the curved glass pieces that complete the candelabras on the open surrounds of Guimard’s Paris metro entrances, we have adopted the term used at the time by the CMP (Compagnie du chemin de fer métropolitain de Paris), “signaling glass”, rather than “globe”, which refers to an image of a sphere [2]. Due to the low luminosity of their electric bulb, which is entirely covered by the signaling glass, the function of these lights is nocturnal signaling rather than lighting. This latter function, which Guimard had not foreseen, as it had not been requested [3], was gradually taken over by uncovered lamps installed by CMP on the aediculae and on certain open surrounds. The surrounds of the additional entrances [4], which at the time were used solely for exiting, had neither luminous signage nor lighting.

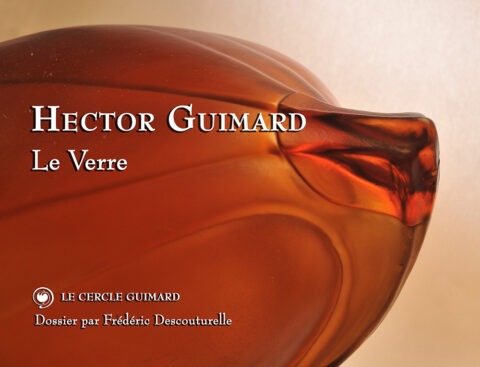

Originally, these signaling glasses were indeed made of glass. For a more complete study, we refer the reader to our dossier Hector Guimard, Le Verre pp. 20-23, published in pdf format in 2009 and still accessible on our website. We give some extracts below.

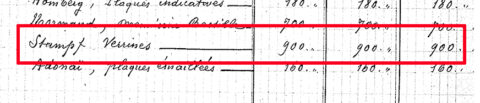

We know the supplier of these signaling glasses thanks to a few rare archives. The first is a CMP accounting document, dated September 12, 1901, listing the names of the various suppliers and the costs incurred with each of them for Guimard’s first project, i.e. the construction of surface accesses for line 1 and two additional sections of future lines 2 and 6. Entitled “Travaux des édicules/M. Guimard Architecte”, this document actually lists the costs incurred for both the aediculae and the uncovered surrounds. The penultimate line of the document reads: “Stumpf, Signaling glass […] 900”.

Detail of a breakdown of surface access expenses for the first Paris metro project. RATP document.

This company, better known as “Cristallerie de Pantin”, had been called Stumpf, Touvier, Viollet et Cie since 1888. It was founded in La Villette in 1851 by E. S. Monot, then transferred to Pantin in 1855. It rapidly prospered, becoming France’s third-largest crystal works (after Baccarat and Clichy) after the 1870 war (and the transfer of the Saint-Louis crystal works to German territory). In 1919, it was absorbed by the Legras glassworks (Saint-Denis and Pantin Quatre-Chemins).

The price of 900 F-gold corresponds to 30 signaling glass at 30 F-gold each, i.e. 13 pairs of signaling glass for the 13 uncovered surrounds of the first project, plus 4 additional pieces in case of breakage. This price per unit is confirmed by another undated CMP accounting document for line 2, which sets the price of two signaling glass for each frame on the section from Villiers to Ménilmontant stations at 60 gold Francs. It was clearly stated that this price was identical to that set for the surrounds on the first site. The Cristallerie de Pantin’s commitment to Guimard and the CMP to maintain the price of glassware for Line 2 surrounds is also the subject of three documents (one handwritten and two typewritten) from November 1901 to January 1903.

There were 103 Guimard surrounds on the network, and twice as many signaling glass on their lampposts. They were still in place in 1960, when Louis Malle filmed ” Zazie dans le métro”, based on the novel by Raymond Queneau.

Catherine Demongeot for Zazie dans le Métro in 1960, promotional photo or set photo for a scene not included in the film. The signaling glass shows the characteristic glass stopper at the tip. Private collection.

Early loans (later transformed into donations) of Guimard surrounds, complete or otherwise, enabled the preservation of their glass cases. Thus, the portico of the uncovered surround at Raspail station, installed in 1906, entered the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1958. The same is true of the surround for Bolivar station, installed in 1911, which entered the collections of the Staatliches Museum für Angewandte Kunst in Munich in 1960 (not on display).

Portico from the uncovered surround of the Raspail station at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The portico includes red glass signaling glass. All rights reserved.

In 1961, the Musée National d’Art Moderne de Paris also received a complete surround, one of two from the Montparnasse station (installed in 1910). Returned to the Musée d’Orsay, it can be viewed on the occasion of thematic exhibitions.

Portico of an open surround from the Musée d’Orsay, loaned (then donated) by the RATP in 1961 to the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris, from the Montparnasse station (1910), with the exception of the enameled lava sign (before 1903). The signaling glasses are indeed glass. Photo D. Magdelaine.

Shortly afterwards, in 1966, the RATP donated a complete Guimard surround (without sign holder) to the Montreal metro company. The seven-module long, five-module wide entourage was composed from elements taken from the reserves and resulting from the dismantling of certain entrances. It included two glass signaling glass

The Guimard open surround for Montreal’s Victoria metro station, in storage prior to shipment in 1966. Photo RATP.

So it was only later, at a date that is still difficult to pin down, that RATP replaced the glass signaling glass with red synthetic equivalents, which were cheaper, less fragile, but far less beautiful. However, as a symptom of RATP’s long lack of interest in this period of its history, the signaling glass that had been salvaged from these exchanges mysteriously disappeared from its reserves, so that by the end of the twentieth century it no longer possessed a single one.

As luck would have it, during restoration work on the entrance to Montreal’s Victoria station, the STP metro company had the wisdom to replace its somewhat damaged glass signaling glass and give one back to the RATP in 2003 [5]. This was the first signaling glass we had the opportunity to examine up close, admiring its clean lines, satin-finish surface and color, which varies from dark red to light orange, depending on the lighting and the thickness of the glass.

Glass signaling glass of an uncovered Guimard surround, from the uncovered surround offered to Montreal in 1966 and donated to the RATP in 2003. Photo F. D.

We have also learned of the existence of a signaling glass [6], also red, on a copy of a Guimard bronze surround in the USA. This unexpected presence, attested to by a State report [7] drawn up in 2002, confirms the existence of a network for the fraudulent export of Guimard metro parts to the USA.

Copy of a bronze surround placed around a pond in Houston in the 2000s. Photo Artcurial.

For the supply of special glass for the windows and roofs of kiosks and pavilions, we have a contract between CMP (Compagnie du Métro Parisien) , Compagnie de Saint-Gobain and glassmaker Charles Champigneulle. This contract clearly specifies the color of the glass prescribed. However, we have no record of an initial contract for the supply of the signaling glass, which would undoubtedly have enabled us to know the color originally envisaged by Guimard. Given the color of the known glass signaling glass, all orange-red, we logically assumed that they all were. This opinion was supported by the fact that on some old black-and-white shots, considering the reflection of light, the signaling glass appears to be dark, which is compatible with a red color.

Uncovered surround of the Rome station, installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

However, this opinion has been challenged by several facts.

The first, to which we should have paid more attention, is the autochrome photograph (giving the actual colors) of Porte d’Auteuil station, dated May 1, 1920 and held in the collection of the Musée Départemental Albert-Kahn. We were unable to reproduce this photograph in the book Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro due to the museum’s opposition to its publication. Since then, having been included in an exhibition, it has been re-photographed by visitors and is now accessible to all thanks to Wikipedia.

.

Surround of the Porte d’Auteuil station. Photo Heinrich Stürzl, based on an autochrome plate by Frédéric Gadmer, taken May 1, 1920. Musée départemental Albert-Kahn collection (inv. A 21 126). Source Wikimedia Commons.

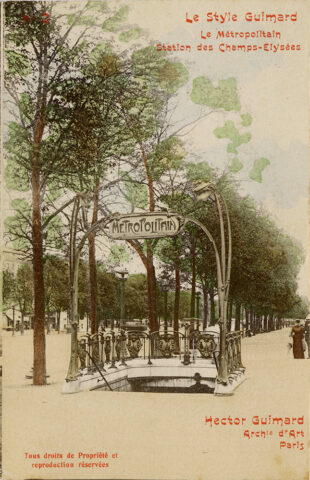

This picture clearly shows that the signaling glasses are white, not red. To the best of our knowledge, we have no other autochrome images of the period. In our opinion, colorized postcards such as those in the “Le Style Guimard” series, published in 1903 on Hector Guimard’s initiative, cannot serve as a reliable reference, since the process consists in softening the contrast of a black-and-white shot and superimposing transparent flat tints of color which, while often plausible, are sometimes different from reality.

Antique postcard “Le Style Guimard” published in 1903. Private collection.

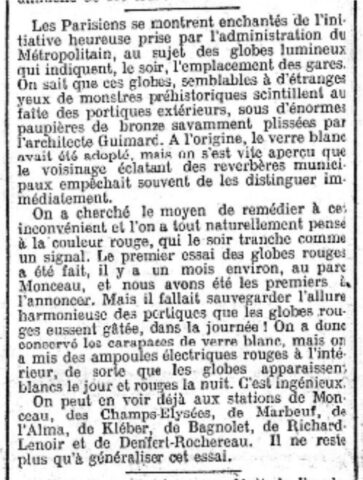

Secondly, the existence of an article published in 1907 in the conservative daily Le Gaulois definitively calls into question the certainty of the exclusive red color of the signaling glasses. We missed this newspaper article in 2003 and 2012. We owe its discovery to an author we will not name.

Unnamed author : echoes from everywhere Le Gaulois September 18, 1907.

This article begins by explaining why red was preferred to white: more effective night-time signage. It also seems to settle the question of the change of color by establishing that in August 1907, CMP carried out a trial of red signaling glasses on the open surround of Monceau station (line 2), and that a month later, in September 1907, seven more stations were fitted with them. At the same time, on other Guimard surrounds, the CMP had obtained a red color by placing red bulbs in the white glasses. It should be noted in passing that the author justifies this temporary measure by “[safeguarding] the harmonious allure of the porticos, which the red globes would have spoiled during the day”. This justification is all the more strange given that red, acting as a complementary color to the green of the fonts, is more pleasing to the eye than white. Did the journalist copy a “piece of language” communicated by the CMP?

By 1907, red signaling glasses were destined to gradually replace white ones. And yet, it is highly likely that the surrounds of Rome station, photographed with certainty in 1903, already featured red glasses, as can be seen in this enlargement of Charles Maindron’s photograph (see above).

Open surround of the Rome station (detail), installed in 1902. Photo Charles Maindron (1861-1940) CMP photographer. Silver chloride gelatin print developed on June 5, 1903. École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées, Direction de la documentation, des archives et du patrimoine.

On the contrary, the autochrome plate of the Porte d’Auteuil surround (see above) shows white signaling glasses. In this case, however, it was one of the very last Guimard surrounds to be installed by the CMP, on line 10 in 1913 [8]. Logically, therefore, it should have been fitted with red glasses. But at a time when there was no doubt talk of definitively abandoning the use of Guimard entrances, it is likely that white signaling glasses from earlier replacements were used.

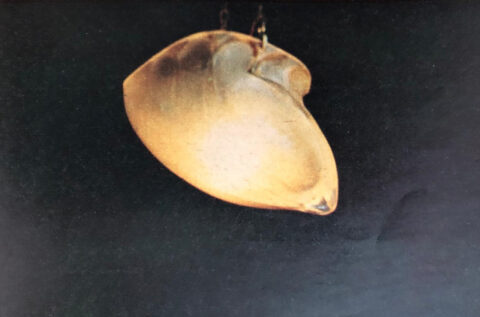

To conclude this little study, we finally had the opportunity to discover the image of a white signaling glass thanks to the photographic collection bequeathed to The Cercle Guimard by our friend Laurent Sully Jaulmes. It is just a detail from a very surprising shot taken in Germany in 1967, which we’ll come back to one day. On this occasion, the signaling glass was used as a chandelier.

White signaling glass used as a chandelier. Photo Laurent Sully Jaulmes (detail), 1967. Cercle Guimard archives and documentation center.

So we don’t despair of seeing signaling glass arrive on the art market in the next few years, because we can’t believe that almost all of those that were originally set up have subsequently been destroyed. On the contrary, a sufficient number of them must still be in private storage. As new generations arrive, they will inevitably reappear, allowing us to take a closer look at these magnificent glass vessels, whether red or white.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Translation: Alan Bryden

Notes

[1] Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Le Métropolitain de Guimard, éditions Somogy, 2003; Descouturelle Frédéric, Mignard André, Rodriguez Michel, Guimard, L’Art nouveau du métro, éditions de La Vie du Rail, 2012. [2] One of the earliest designs for a surround with a rounded base, project no. 2, was not validated by the authorities, and featured globular-shaped signaling glasses clamped in a cast-iron jaw, see our article Un porte-enseigne défaillant sur les entourages découverts du métro. [3] The 1899 competition (in which Guimard did not take part) stipulated the presence of a signpost for open surrounds, without mentioning a light source. However, most candidates included one in their proposals. [4] Low cartouche surrounds installed on the network from 1903-1904. [5] The other signaling glass was entrusted to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. [6] One of the signaling glasses was then stored and replaced by an equivalent in synthetic material. [7] This condition report, carried out at the home of the owner of the surround copy in Houston, was written on June 27, 2002 and signed by Steven L. Pine, decorative arts conservator at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and a specialist in metal conservation. It refers to a previous report of June l6, 1999. [8] It also shared with the Chardon-Lagache station a peculiarity in the way the crests were hung, a sign, perhaps, of a change in the assembly teams.

The future of the Hotel Mezzara is being decided now

The long-awaited moment has arrived: the invitation to tender for the long administrative lease to develop the Hôtel Mezzara has just been published. This is the third invitation to tender – the previous two having been declared unsuccessful – issued by the French State, which owns the site. That is why Fabelsi-Hector Guimard Diffusion and the Cercle Guimard are once again bidding. Our project is a unique opportunity for Paris and for everyone to enjoy.

Hôtel Mezzara, 60 rue Jean-de-la-Fontaine à Paris (75016).

Since 2015, the Hôtel Mezzara has been emptied of its last occupants when it ceased to be used as a boarding annex for the Lycée Jean Zay. Since then, and in particular during the two exhibitions that we were able to stage there in 2017 and 2018, we have constantly stressed the need for this site not to be privatised, but instead to be made available to the public by being transformed into a museum space dedicated to Hector Guimard and the decorative arts of his time, a place that is alive, accessible and faithful to his exceptional heritage, while bringing it fully into the 21st century. Over the past decade, we have received a great deal of support and offers of partnership that have strengthened the solidity of our project.

On Thursday 6 February, our team visited the site to refine our proposal, considering the development of the site and our collection of works.

The Cercle Guimard and Fabelsi-Hector Guimard Diffusion in the lobby of the Hôtel Mezzara on 6 February 2025.

After the visit, working session in our office at Castel Béranger.

In the coming weeks, we invite you to follow a series of publications on LinkedIn@LeCercleGuimard. to discover what goes on behind the scenes of this candidacy. We’ll be sharing:

– Our partners and supporters, who are enriching and strengthening our project.

– The key stages of the bid, so that you can experience the adventure in real time.

– Exclusive works from our collection, offering a foretaste of the future institution.

– Our vision for the Hôtel Mezzara, a dynamic centre for research, mediation and the dissemination of Art Nouveau.

Share, support and pass on our efforts to give the Hotel Mezzara the place it deserves in our cultural heritage.

The executive committee of the Cercle Guimard

Nancy-Paris, Paris-Nancy – 1

After mentioning the Vallin exhibition held at the Villa La Garenne in Liverdun during the summer of 2022, we begin a series of three articles showing some of the reciprocal influences between the artists of the Nancy School and those of the Parisian Art Nouveau, focusing on architecture.

The history of the interaction between the naturalist style of the Nancy School and the more linear styles of Parisian Art Nouveau and Belgian Art Nouveau has already been largely studied[1]. It is made of back and forth between the angles of this isosceles triangle, angles 320 km apart. If the people of Brussels had the initiative in the field of architecture, it is true that the people of Nancy became famous early on in the decorative arts by the quality and volume of their production. The relationship between these three creative centers was, however, asymmetrical, also reproducing the economic and political strength of each of these poles, for if local success was possible in Nancy and even more so in Brussels, recognition and the passage to a higher financial dimension went through Paris. Henry Van de Velde from Brussels and Émile Gallé and Louis Majorelle from Nancy understood this perfectly because they established themselves there as quickly as they could. If the graft did not take for Van de Velde, who was forced into exile in Germany, it succeeded commercially for Gallé, helped by his social and literary relations with the Parisian intellectual milieu, and even more so for Majorelle, thanks to the friendships and professional relationships he developed during his time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It was also at the ENBA in Paris that Nancy’s Victor Prouvé, Louis Majorelle and Jacques Gruber were trained, before they made their mark in the field of decorative art. As for Camille Gauthier, one of the most brilliant representatives of the second generation of the Nancy School, he was a student at the École nationale des arts décoratifs in Paris from 1891 before being hired by Majorelle in 1893. The question of this professional training was bitterly debated in Nancy, where despite the gradual but very slow transformation of a municipal school of drawing into a true school of fine arts, the new generation of Nancy architects, the one that was active in the 1900s, studied at the École nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where they often retained connections. These architects gained a prestige that their predecessors, trained in the established architectural firms and at the École Professionnelle de l’Est, did not have.

The influence of Nancy on Guimard

Known in Paris since the Universal Exhibition of 1878, famous since the exhibition La Pierre, le Bois, la Terre, le Verre organized by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in 1884, and finally crowned at the Universal Exhibition of 1889, Émile Gallé has largely contributed to a renewed use of the plant by the decorative arts. This influence is partly responsible for the numerous floral representations that were to be found in Parisian Art Nouveau, for example at Lalique, but also, almost unexpectedly, in the first part of Hector Guimard’s career. Until 1895, the latter practiced a style that was still eclectic but so recognizable and innovative that it can be described as proto-Art Nouveau. It is particularly evident in his creations of architectural ceramic panels, for which we refer to the third and fourth articles in our series on the Muller ceramic company.

Tympanum of the window of the 2nd floor of the right facade of the Hotel Jassedé by Guimard, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache in Paris, 1893. Two glazed earthenware panels. Photo F.D.

If the stylistic impulse did come from Nancy, we are witnessing here a complete reworking of the composition of these panels, which moves away from Emile Gallé’s descriptive use of botany. On the contrary, in a very short time, Guimard managed to produce perfectly mastered stylizations of floral motifs that had nothing to envy those presented a little later in 1897 in the portfolio La Plante et ses applications ornementales by Eugène Grasset and his students. The most visible Nancy imprint on a Guimard work is found on the ornamental fonts of the Sacred Heart school, 9 avenue de la Frillière, Paris XVIe, in 1895. The capitals of the columns dividing the large bays of the second floor into three have a very recognizable leaf and flower motif of the thistle, a plant not directly related to the iconography of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

.

Capital of the cast iron columns of unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the windows of the second floor of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

This plant has been the emblem of the city of Nancy since the 15th century, appearing on its coat of arms along with the motto “non inultus premor”. It has thus become a naturalist identification motif that Nancy’s inhabitants have used extensively and continuously in all branches of decorative art.

Large silver thistle brooch by Ferdinand Kauffer, model created around 1886. Phototype published in La Lorraine Artiste in 1894, reproduced in Martin, Étienne, Bijoux Art nouveau Nancy 1890-1920, éditions du quotidien, 2015.

Project for the entrance portico of the École de Nancy at the 1902 exhibition of decorative art in Turin (not realized) by Émile André. Watercolor drawing, Musée de l’École de Nancy.

Catalog of the SLAA exhibition at the International Exhibition of Eastern France in 1909, drawing by Henri Bergé. Private collection.

Even more interesting, the inclined cast iron pillars that support the second floor of the Sacred Heart School have been decorated with motifs that are no longer descriptive this time but very clearly evoke the bud and indentation of the thistle leaves.

Cast iron pillar by an unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the courtyard of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

From his period strictly speaking Art Nouveau, the one that begins in 1895 with the Castel Béranger, Guimard abandoned the naturalistic and botanical representation to keep only the spirit. He thus adhered to the aesthetic advocated by the Brussels-based Victor Horta, while inventing – and constantly reinventing – his own style, soon to be copied by a host of followers. However, Guimard did not totally banish the plant from his creation. It may have reappeared from time to time, but always in a form that is not botanically identifiable. Thus, we find indentations applied to the base of the rear pillars of the A aedicula (1900)[2].

Rear pillar of the A-aedicula of the Abbesses station. Photo F.D.

Leaves and fruits carved on the lintel of the entrance door of 43 rue Gros (1909-1911.

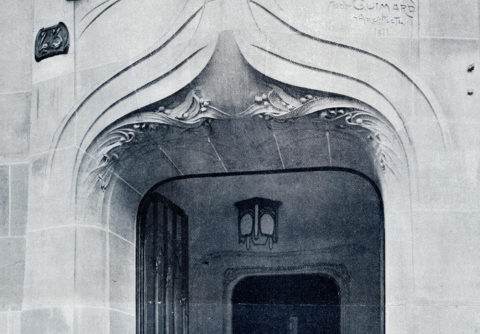

Entrance door of the building at 43 rue Gros in Paris by Guimard (1909-1911). La Construction moderne, February 9, 1913.

The ceiling light of the hallway is visible on the previous picture. It is part of the Lustres Lumière created by Guimard from 1909. On its bronze plates, we can also see leaves or blades of grass intertwined.

Bronze element of the Lustres Lumière. Photo F.D.

Later, in 1922, on the jambs of the Grunwaldt tomb, in the new cemetery of Neuilly-sur-Seine, the sculpted decoration mixes laurel and palm branches, two common species in the cemetery repertoire. These two plants, which are also used in the decoration of this small monument, symbolize the glory of the deceased.

Carved plant decoration on a jamb of the Grunwald burial, 1922. Photo F.D.

2- The influence of the Parisian Art Nouveau and of Guimard in Nancy

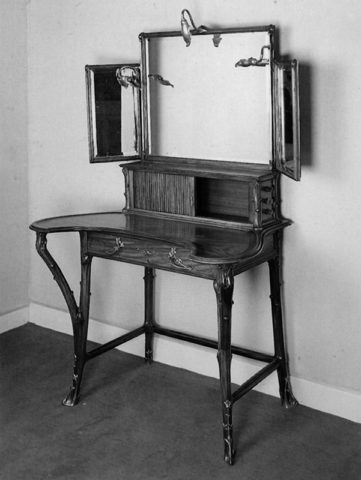

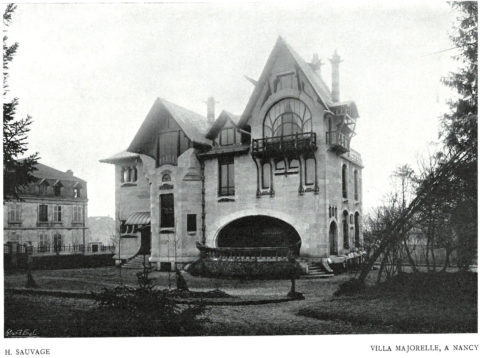

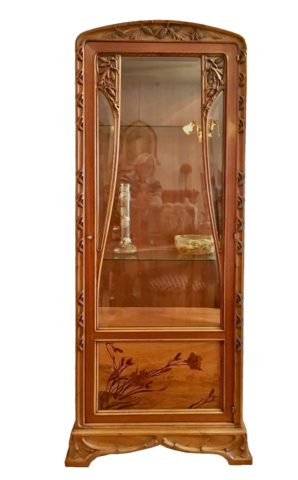

For his part, Guimard never built or decorated anything in Nancy. Moreover, at the present time, no archive allows us to say that he even visited the city, and yet his influence on the city is very real. It was realized through the intermediary of fellow Parisian architects who knew how to compose with the naturalism in vogue in Nancy. The first of these was of course his friend Henri Sauvage, who built the villa of furniture manufacturer Louis Majorelle in Nancy. This choice of a young, inexperienced Parisian architect is significant, as Majorelle was both a bridgehead of the Nancy style in Paris and a bridgehead of the Parisian style in Nancy. An emulator of Gallé in the field of cabinetmaking from 1895 on, he did not give his style a truly personal dimension until shortly before the 1900 World’s Fair, when he moved closer to the Parisian style. This orientation was undoubtedly favored by the work of the young Camille Gauthier, trained at the National School of Decorative Arts and hired by Majorelle from 1893 to 1900. It was also inspired by certain Parisian models such as this dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, whose legs split into two to support a console

Dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, 1898. Museum of the École de Nancy. Photograph taken from the book Majorelle by Roselyne Bouvier. La Bibliothèque des arts, 1997. Photo A. Fellmann.

This arrangement of the legs, provided with thorns on the Plumet/Selmersheim dressing table (and thus clearly designated as plant stems in the manner from Nancy) was largely taken up again a little later on part of the furniture presented by Majorelle at the World Fair of 1900. His furniture then presented a more continuous dynamic line (more “Parisian”) underlined by a water lily stem in gilded bronze.

Desk with water lilies by Majorelle. Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1900. Portfolio Meubles de style moderne Exposition Universelle de 1900, Charles Schmid éditeur. Private collection.

Majorelle also collaborated with the Parisian Henri Sauvage in 1898 for three lounges of the Café de Paris (41 avenue de l’Opéra).

Ceiling of one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

Mantelpiece in one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

This Parisian realization of Majorelle preluded the construction of his villa in Nancy designed by the same architect in 1901-1902 with the intervention of two other Parisians: the ceramist Alexandre Bigot and the young painter Francis Jourdain, son of the architect Frantz Jourdain, another friend of Guimard.

North facade of the Villa Majorelle in Nancy, excerpt from an article by Frantz Jourdain in L’Art Décoratif, August 1902. Digital library limedia.

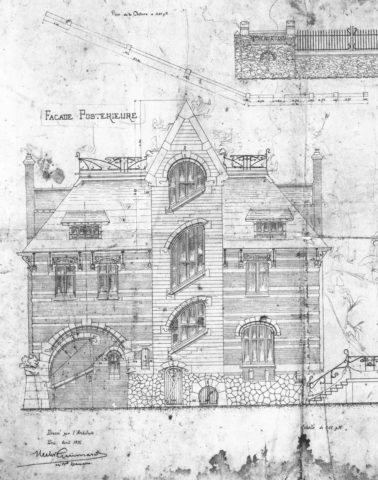

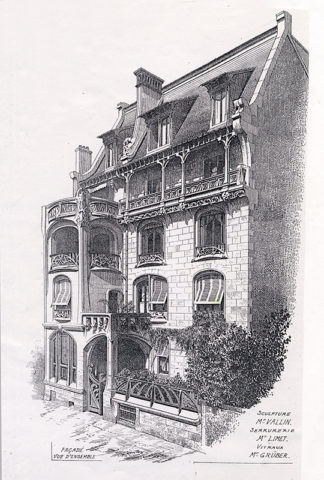

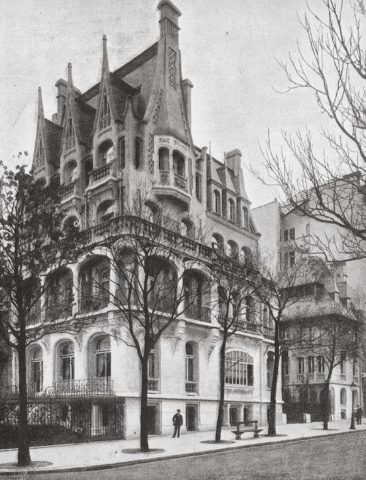

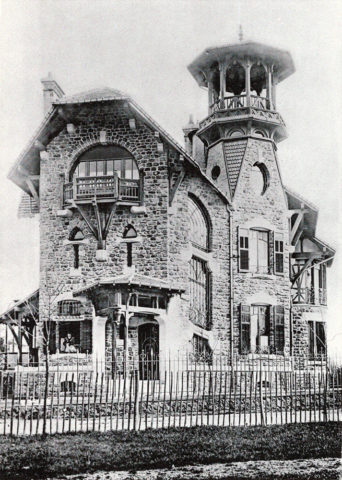

It is easy to recognize in this northern facade of the Majorelle villa a clear influence of the rear facade of Villa Berthe built by Guimard at Le Vésinet in 1896.

Plan of the rear façade of Villa Berthe, dated 1896.

Another Parisian architect, Jacques-René Hermant, came to Nancy relatively early to build the Maison Luc in 1901-1902.

Victor Luc House, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

Its symmetrically ordered facade in bays and levels conceals beautiful details such as the capitals of the porch columns, the ceramics of the cornice and the ironwork with its linear curves. Inside, a glazed stoneware staircase by Gentil & Bourdet is one of the most remarkable achievements of this Parisian firm whose protagonist, François Eugène Bourdet, was a young architect from Nancy.

Victor Luc house, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Detail of the porch. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

These last two residences influenced Nancy architects and the Villa Majorelle even became one of the driving forces of modern architecture in Nancy. But in parallel to this Parisian trend, another trend, more locally inspired, was led by the Vallin-Biet duo who had just completed the Biet building. For this local trend, the filiation with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was also present, but the structure of the buildings was more unitary and organic. As we will see in a later article, Guimard and Vallin were able – separately – to exploit certain themes such as the representation of the deformation of matter.

Biet building, 22 rue de la Commanderie in Nancy, 1901-1902. Portfolio Motifs d’architecture moderne, undated (ca. 1905).

Many Nancy architects, such as Émile André and Lucien Weissenburger, then took decorative details from both buildings. On the Houot house or on the Fernbach villa of Émile André, the windowsills are borrowed from the Majorelle villa of Sauvage.

Window sill of the villa Majorelle à Nancy by Henri Sauvage, 1901-1902. Photo F.D.

Window sill of the Houot house, 92 bis quai de la Bataille in Nancy by Émile André, 1903. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

The same architect, Emile André, borrowed the peristyles of the third floor balconies of his buildings at 69 and 71 Avenue Foch in Nancy from another Parisian architect, Charles Plumet, a precursor of the Art Nouveau style.