Month: December 2022

Nancy-Paris, Paris-Nancy – 1

After mentioning the Vallin exhibition held at the Villa La Garenne in Liverdun during the summer of 2022, we begin a series of three articles showing some of the reciprocal influences between the artists of the Nancy School and those of the Parisian Art Nouveau, focusing on architecture.

The history of the interaction between the naturalist style of the Nancy School and the more linear styles of Parisian Art Nouveau and Belgian Art Nouveau has already been largely studied[1]. It is made of back and forth between the angles of this isosceles triangle, angles 320 km apart. If the people of Brussels had the initiative in the field of architecture, it is true that the people of Nancy became famous early on in the decorative arts by the quality and volume of their production. The relationship between these three creative centers was, however, asymmetrical, also reproducing the economic and political strength of each of these poles, for if local success was possible in Nancy and even more so in Brussels, recognition and the passage to a higher financial dimension went through Paris. Henry Van de Velde from Brussels and Émile Gallé and Louis Majorelle from Nancy understood this perfectly because they established themselves there as quickly as they could. If the graft did not take for Van de Velde, who was forced into exile in Germany, it succeeded commercially for Gallé, helped by his social and literary relations with the Parisian intellectual milieu, and even more so for Majorelle, thanks to the friendships and professional relationships he developed during his time at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. It was also at the ENBA in Paris that Nancy’s Victor Prouvé, Louis Majorelle and Jacques Gruber were trained, before they made their mark in the field of decorative art. As for Camille Gauthier, one of the most brilliant representatives of the second generation of the Nancy School, he was a student at the École nationale des arts décoratifs in Paris from 1891 before being hired by Majorelle in 1893. The question of this professional training was bitterly debated in Nancy, where despite the gradual but very slow transformation of a municipal school of drawing into a true school of fine arts, the new generation of Nancy architects, the one that was active in the 1900s, studied at the École nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, where they often retained connections. These architects gained a prestige that their predecessors, trained in the established architectural firms and at the École Professionnelle de l’Est, did not have.

The influence of Nancy on Guimard

Known in Paris since the Universal Exhibition of 1878, famous since the exhibition La Pierre, le Bois, la Terre, le Verre organized by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs in 1884, and finally crowned at the Universal Exhibition of 1889, Émile Gallé has largely contributed to a renewed use of the plant by the decorative arts. This influence is partly responsible for the numerous floral representations that were to be found in Parisian Art Nouveau, for example at Lalique, but also, almost unexpectedly, in the first part of Hector Guimard’s career. Until 1895, the latter practiced a style that was still eclectic but so recognizable and innovative that it can be described as proto-Art Nouveau. It is particularly evident in his creations of architectural ceramic panels, for which we refer to the third and fourth articles in our series on the Muller ceramic company.

Tympanum of the window of the 2nd floor of the right facade of the Hotel Jassedé by Guimard, 41 rue Chardon-Lagache in Paris, 1893. Two glazed earthenware panels. Photo F.D.

If the stylistic impulse did come from Nancy, we are witnessing here a complete reworking of the composition of these panels, which moves away from Emile Gallé’s descriptive use of botany. On the contrary, in a very short time, Guimard managed to produce perfectly mastered stylizations of floral motifs that had nothing to envy those presented a little later in 1897 in the portfolio La Plante et ses applications ornementales by Eugène Grasset and his students. The most visible Nancy imprint on a Guimard work is found on the ornamental fonts of the Sacred Heart school, 9 avenue de la Frillière, Paris XVIe, in 1895. The capitals of the columns dividing the large bays of the second floor into three have a very recognizable leaf and flower motif of the thistle, a plant not directly related to the iconography of the Sacred Heart of Jesus

.

Capital of the cast iron columns of unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the windows of the second floor of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

This plant has been the emblem of the city of Nancy since the 15th century, appearing on its coat of arms along with the motto “non inultus premor”. It has thus become a naturalist identification motif that Nancy’s inhabitants have used extensively and continuously in all branches of decorative art.

Large silver thistle brooch by Ferdinand Kauffer, model created around 1886. Phototype published in La Lorraine Artiste in 1894, reproduced in Martin, Étienne, Bijoux Art nouveau Nancy 1890-1920, éditions du quotidien, 2015.

Project for the entrance portico of the École de Nancy at the 1902 exhibition of decorative art in Turin (not realized) by Émile André. Watercolor drawing, Musée de l’École de Nancy.

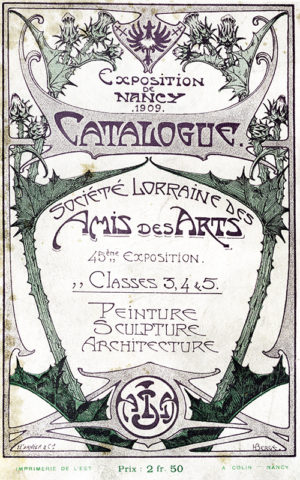

Catalog of the SLAA exhibition at the International Exhibition of Eastern France in 1909, drawing by Henri Bergé. Private collection.

Even more interesting, the inclined cast iron pillars that support the second floor of the Sacred Heart School have been decorated with motifs that are no longer descriptive this time but very clearly evoke the bud and indentation of the thistle leaves.

Cast iron pillar by an unknown manufacturer supporting the lintel of the courtyard of the Sacred Heart School, 9 avenue de la Frillière in Paris, 1895. Photo F.D.

From his period strictly speaking Art Nouveau, the one that begins in 1895 with the Castel Béranger, Guimard abandoned the naturalistic and botanical representation to keep only the spirit. He thus adhered to the aesthetic advocated by the Brussels-based Victor Horta, while inventing – and constantly reinventing – his own style, soon to be copied by a host of followers. However, Guimard did not totally banish the plant from his creation. It may have reappeared from time to time, but always in a form that is not botanically identifiable. Thus, we find indentations applied to the base of the rear pillars of the A aedicula (1900)[2].

Rear pillar of the A-aedicula of the Abbesses station. Photo F.D.

Leaves and fruits carved on the lintel of the entrance door of 43 rue Gros (1909-1911.

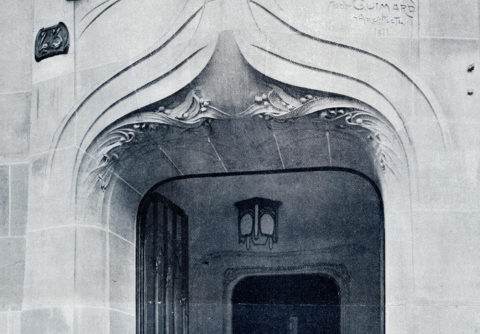

Entrance door of the building at 43 rue Gros in Paris by Guimard (1909-1911). La Construction moderne, February 9, 1913.

The ceiling light of the hallway is visible on the previous picture. It is part of the Lustres Lumière created by Guimard from 1909. On its bronze plates, we can also see leaves or blades of grass intertwined.

Bronze element of the Lustres Lumière. Photo F.D.

Later, in 1922, on the jambs of the Grunwaldt tomb, in the new cemetery of Neuilly-sur-Seine, the sculpted decoration mixes laurel and palm branches, two common species in the cemetery repertoire. These two plants, which are also used in the decoration of this small monument, symbolize the glory of the deceased.

Carved plant decoration on a jamb of the Grunwald burial, 1922. Photo F.D.

2- The influence of the Parisian Art Nouveau and of Guimard in Nancy

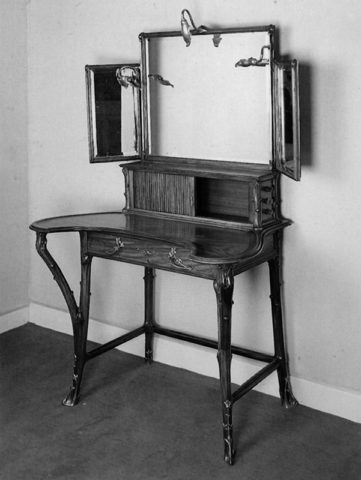

For his part, Guimard never built or decorated anything in Nancy. Moreover, at the present time, no archive allows us to say that he even visited the city, and yet his influence on the city is very real. It was realized through the intermediary of fellow Parisian architects who knew how to compose with the naturalism in vogue in Nancy. The first of these was of course his friend Henri Sauvage, who built the villa of furniture manufacturer Louis Majorelle in Nancy. This choice of a young, inexperienced Parisian architect is significant, as Majorelle was both a bridgehead of the Nancy style in Paris and a bridgehead of the Parisian style in Nancy. An emulator of Gallé in the field of cabinetmaking from 1895 on, he did not give his style a truly personal dimension until shortly before the 1900 World’s Fair, when he moved closer to the Parisian style. This orientation was undoubtedly favored by the work of the young Camille Gauthier, trained at the National School of Decorative Arts and hired by Majorelle from 1893 to 1900. It was also inspired by certain Parisian models such as this dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, whose legs split into two to support a console

Dressing table by Charles Plumet and Tony Selmersheim, 1898. Museum of the École de Nancy. Photograph taken from the book Majorelle by Roselyne Bouvier. La Bibliothèque des arts, 1997. Photo A. Fellmann.

This arrangement of the legs, provided with thorns on the Plumet/Selmersheim dressing table (and thus clearly designated as plant stems in the manner from Nancy) was largely taken up again a little later on part of the furniture presented by Majorelle at the World Fair of 1900. His furniture then presented a more continuous dynamic line (more “Parisian”) underlined by a water lily stem in gilded bronze.

Desk with water lilies by Majorelle. Universal Exhibition of Paris in 1900. Portfolio Meubles de style moderne Exposition Universelle de 1900, Charles Schmid éditeur. Private collection.

Majorelle also collaborated with the Parisian Henri Sauvage in 1898 for three lounges of the Café de Paris (41 avenue de l’Opéra).

Ceiling of one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

Mantelpiece in one of the three lounges furnished and decorated by Louis Majorelle at the Café de Paris in 1898. German portfolio Modern Bautishler-Arbeiten, pl. 53, August 1902.

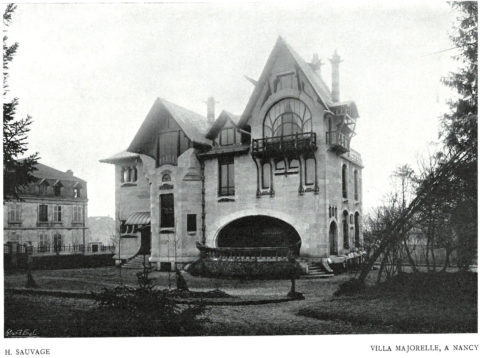

This Parisian realization of Majorelle preluded the construction of his villa in Nancy designed by the same architect in 1901-1902 with the intervention of two other Parisians: the ceramist Alexandre Bigot and the young painter Francis Jourdain, son of the architect Frantz Jourdain, another friend of Guimard.

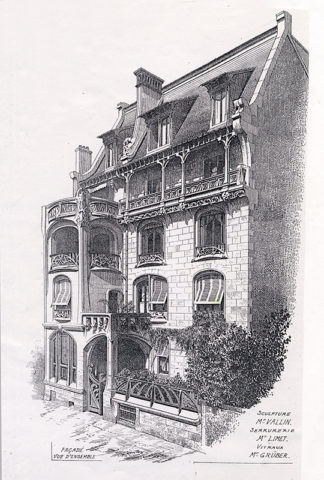

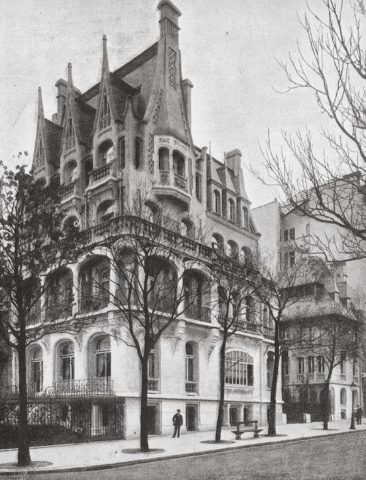

North facade of the Villa Majorelle in Nancy, excerpt from an article by Frantz Jourdain in L’Art Décoratif, August 1902. Digital library limedia.

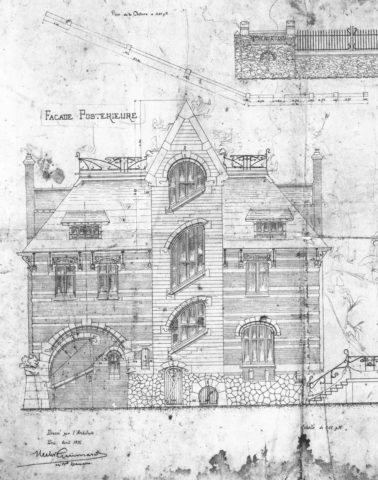

It is easy to recognize in this northern facade of the Majorelle villa a clear influence of the rear facade of Villa Berthe built by Guimard at Le Vésinet in 1896.

Plan of the rear façade of Villa Berthe, dated 1896.

Another Parisian architect, Jacques-René Hermant, came to Nancy relatively early to build the Maison Luc in 1901-1902.

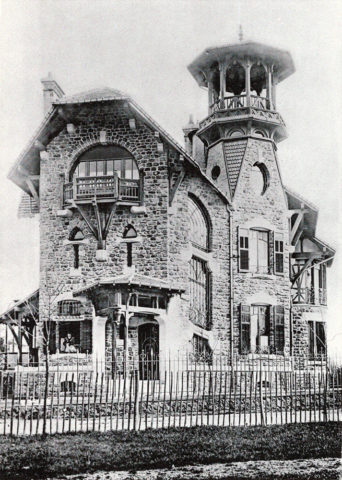

Victor Luc House, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

Its symmetrically ordered facade in bays and levels conceals beautiful details such as the capitals of the porch columns, the ceramics of the cornice and the ironwork with its linear curves. Inside, a glazed stoneware staircase by Gentil & Bourdet is one of the most remarkable achievements of this Parisian firm whose protagonist, François Eugène Bourdet, was a young architect from Nancy.

Victor Luc house, 25 rue de Malzéville in Nancy, by Jacques-René Hermant, 1901-1902. Detail of the porch. Photo Nicholas Christodoulidis.

These last two residences influenced Nancy architects and the Villa Majorelle even became one of the driving forces of modern architecture in Nancy. But in parallel to this Parisian trend, another trend, more locally inspired, was led by the Vallin-Biet duo who had just completed the Biet building. For this local trend, the filiation with the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was also present, but the structure of the buildings was more unitary and organic. As we will see in a later article, Guimard and Vallin were able – separately – to exploit certain themes such as the representation of the deformation of matter.

Biet building, 22 rue de la Commanderie in Nancy, 1901-1902. Portfolio Motifs d’architecture moderne, undated (ca. 1905).

Many Nancy architects, such as Émile André and Lucien Weissenburger, then took decorative details from both buildings. On the Houot house or on the Fernbach villa of Émile André, the windowsills are borrowed from the Majorelle villa of Sauvage.

Window sill of the villa Majorelle à Nancy by Henri Sauvage, 1901-1902. Photo F.D.

Window sill of the Houot house, 92 bis quai de la Bataille in Nancy by Émile André, 1903. Portfolio Nouvelles Constructions de Nancy, pl. XXV. Private collection.

The same architect, Emile André, borrowed the peristyles of the third floor balconies of his buildings at 69 and 71 Avenue Foch in Nancy from another Parisian architect, Charles Plumet, a precursor of the Art Nouveau style.

Lombard building (left) at 69 avenue Foch in Nancy (1902-1903) and France-Lanord building (right) at 71 avenue Foch in Nancy (1902-1904), Émile André. Photo F.D.

Plumet had developed these peristyles on several of his Parisian buildings from 1897 (36 rue de Tocqueville) and had reused them on numerous occasions.

Private mansion by Charles Plumet, at the corner of 28 avenue Foch and 90 avenue Malakoff in Paris, seen from the avenue Malakoff side, 1900. Photo published in the German magazine Die Architektur des XX. Jahrhunderts. Private collection.

Also in the Villa Majorelle, the frame of the first floor doors, glazed over two-thirds of the height, is of particular interest. At the base of the glazed part, a small wood is obliquely detached from each side jamb, then becomes vertical and joins the upper crosspiece, evoking a rejection born of a trunk. Moreover, this glazed part is intersected at the top by a simple horizontal line.

Door of the dining room of the Villa Majorelle by Henri Sauvage. Photo F.D.

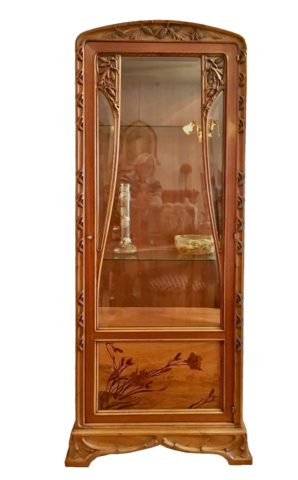

Louis Majorelle used this layout on a series of display cases with or without the addition of naturalist decoration.

Louis Majorelle, pinecones display case, model n° 244, height 1 m 90, sold 900 F-gold in 1914. Photo website Anticstore, Galerie Vaudémont, Nancy. All rights reserved.

This arrangement is directly reproduced on the doors of several of Guimard’s showcases, the earliest of which is reproduced in an article by Frantz Jourdain published in the first issue of the Revue d’Art (for which Guimard had designed the cover) in November 1899.

Little table and display case by Guimard photographed at Castle Béranger. Photo published in the Revue d’Art n°1 in November 1899.

This door is more visible on this later window that was in the Guimard Hotel.

Display case by Guimard having been in the Guimard Hotel 122 avenue Mozart. Private collection.

Other influences of Guimard’s work exist in Nancy, even if they are not in very large numbers. Rather, they came about through the publication of his work in magazines and through the travels of Nancy residents to Paris. It is undoubtedly by one or the other means that Joseph Hornecker, a young Alsatian architect who arrived in Nancy in 1901 and associated with Henri Gutton, was inspired by the Castel Henriette in Sèvres for the Villa Marguerite, built in the Parc de Saurupt in Nancy in 1904.

Villa Marguerite in the park of Saurupt. Portfolio Nouvelles constructions de Nancy. Private collection

Walking through the streets of Nancy, one can also find ornamental castings by Guimard on the windows of about fifteen houses or buildings, many of which are the work of the architect Lavocat. However, these were orders placed directly with the Saint-Dizier foundry by a small number of Nancy architects before the First World War and therefore without any intervention by Guimard.

Large GG balcony and return, building 31 rue Anatole France in Nancy. Photo F.D.

It is not possible to attribute to the influence of Guimard alone the numerous linear-style ironworks that can also be found in Nancy, such as that of the Immeuble Kempf, 40 Cours Léopold by Félicien and Fernand César (1903-1904), or those of the houses at 16 and 20 rue des Bégonias by Désiré Bourgon. But, in addition to the marquise of the Villa La Garenne which was the subject of a previous article, there is a well-known example of a direct transcription of a work of ironwork by Guimard: the door of the Castel Béranger copied by the Nancy locksmith Lucien Collignon for the door of his own house at 55 rue de Boudonville in 1905, that is to say, ten years after Guimard’s.

Door of the maison Collignon, 55 rue de Boudonville in Nancy. Photo all rights reserved.

More anecdotally, on Boulevard Lobau, the counter and its lettering of the commercial building of the coal merchant Jules Kronberg are also to be credited with the influence that Guimard’s style had in Nancy. This “discrepancy” is all the more surprising since Kronberg was a tenant and client of Vallin, who lived almost opposite.

Also in the field of ironwork, the young Parisian Edgard Brandt (1880-1860) had a first creative period in the Art Nouveau style. When he worked in Nancy, he was able to adapt to the local style. At the request of the Nancy architect Joseph Hornecker, he was commissioned in 1907-1909 to carry out a major program at the new headquarters of the SNCI bank (exterior ironwork, lobby and vault).

Hall of the Nancy bank SNCI, architect Joseph Hornecker, 1907-1909, ironworks with pinecones by Edgard Brandt.

For the same Nancy architect and also in 1907, Brandt executed the banister of the main staircase of the town hall of Euville in Meuse. These two creations, both naturalistic (pine cones for the SNCI) and symbolist (oak for the town hall of Euville) are completely in the Nancy style and prelude the gradual evolution of Brandt towards a more refined modern style and then towards Art Deco.

Edgard Brandt, oak leaves and acorns railing of the Euville town hall. Photo: Cédric Amey, under Creative Commons license.

Because of the vigor of the Nancy artistic community, these stylistic exchanges between Nancy and Paris were not solely to the benefit of the capital city and, as we will see in a later article, the Nancy style even made a strong comeback in Paris thanks to the department stores and in particular the powerful Nancy chain of Magasins Réunis.

Frédéric Descouturelle

Thanks to Fabrice Kunégel who pointed out the similarity between the woodwork of the interior doors of the Majorelle villa and those of certain Guimard windows. Thanks also to Koen Roelstraete for his research on the pine cone window of Majorelle.

Translation : Alan Bryden

Notes :

[1] Thanks to numerous articles and the fascinating Paris-Brussels, Brussels-Paris exhibition of 1997 at the Musée d’Orsay and the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent.

[2] Let us point out for the sake of argument that the interpretations we can give of Guimard’s motives are our own. If we think that they can be shared by other observers, we do not want to impose them on anyone.