Month: March 2020

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Three: Muller and Hector Guimard, Hotel Roszé and Hotel Jassedé.

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. In this third article, and then in the next one, we address the collaboration between Muller & Cie and Hector Guimard.

Our articles will not present all of Guimard’s architectural ceramic designs known and intended for Muller nor all of the instances of use of his decorative panels by other architects. This exhaustive study is being carried out in parallel for the constitution of a specific repertory.

Hector Guimard is a special case among the modern architects who supplied models to Muller & Cie, since he called upon the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry for the decoration of his first villas built in the West of Paris in the early 1890s. These orders immediately led to the publication of models. But curiously, as soon as the Castel Béranger was built in 1895-1898, Guimard no longer seemed to place orders with Muller & Cie and turned to Gilardoni & Brault and Alexandre Bigot. Almost a decade later, however, 14 of his models still appear in Muller & Cie’s 1904 catalogue n° 2.

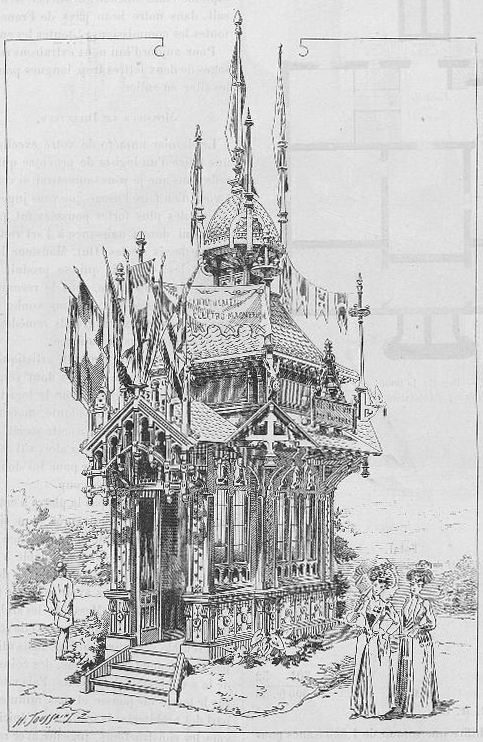

From his first known construction, a modest pavilion praising the therapeutic methods of electricity and electromagnetism[1] for an obscure Ferdinand de Boyères at the 1889 Universal Exhibition, Guimard used ceramics[2] to decorate the panels inserted in the joinery. The professional magazine La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890 gives an engraving of it (probably from a photo) but we do not know which ceramic models were used or who was the supplier.

Guimard’s “Pavillon for the application of electricity to medicine” at the 1889 Universal Exhibition. Illustration by Henri Toussaint published in La Construction Moderne of 22 March 1890. The ceramic decorations are on the basement as well as on the panels separating the windows. Gallica BNF website.

Hotel Roszé

Two years later, in 1891, for the Hotel Roszé at 34 rue Boileau in the 16th arrondissement, we have the certainty of a real collaboration between Guimard and Muller & Cie thanks to the presence of several panels of the Hotel on the 1904 catalogue n° 2. At that time, Guimard was only 24 years old and he was far from having the notoriety that would be his from the Castel Béranger. The novelty of his models, which seems less obvious today, must have been enough for Louis d’Émile Muller to feel that this young architect deserved attention.

The Hotel Roszé, 34 rue Boileau in Paris, photograph taken in 1975. At that time the ceramic panels on the front and back facades were masked by a coat of paint. ©Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

The friezes on either side of the lintel[3] of the first-floor window on the left-hand span of the street facade are clad with four-part panels showing a branch from which a blue and a white flower emerge alternately.

La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Two: Muller and Art Nouveau

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his creations in the field of Art Nouveau. The first article summarized the history of the company. In this second article we look more precisely at the collaborations with the artists and architects of this artistic movement. The third and fourth article will focus on Hector Guimard’s model editions at Muller & Cie and the fith on the fireplace sector.

Following the death of Émile Muller in 1889 after the Universal Exhibition, his son Louis d’Émile Muller took over the management of the company. The latter developed an artistic sector by publishing contemporary artists and intensifying relations with architects for the creation of new models to be published or not.

The private mansion known as La Pagode, built in a Japanese style in 1895-1896 by the architect Alexandre Marcel for the director of Bon Marché, at 57 rue de Babylone in Paris, is a good example of this. Only a part of the enamelled stoneware decoration can be found in the catalogue.

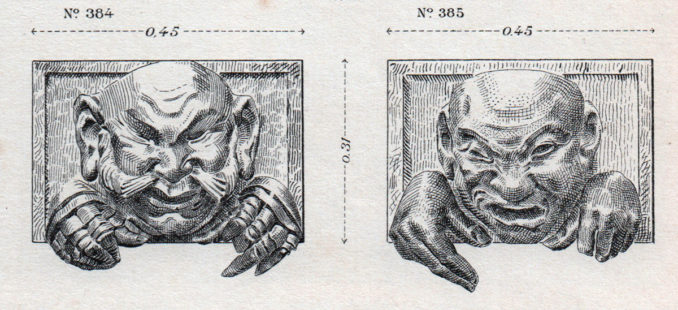

Two panels from the decoration of La Pagode, architect Alexandre Marcel, 1895-1896, 57 rue de Babylone, Paris. Catalogue Muller et Cie No. 2, 1904, pl. 15. Private collection. Each panel: 12 kg; red or white terracotta: 15 F-gold; enamelled terracotta: 30 F-gold; unenamelled stoneware: 20 F-gold; enamelled stoneware: 40 F-gold.

Among the young designers who came into contact with Muller & Cie many will participate in one way or another in the Art Nouveau artistic movement, focused on decorative art and architecture. Their work will generate a large number of new models that are likely to be reused by others. It is therefore essential for a company such as the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry to keep up to date and to be able to supply without delay those architects, contractors and decorators who are not themselves creators but who wish to give their work a modern look. The Muller & Cie catalogues will therefore include a significant number of Art Nouveau style models.

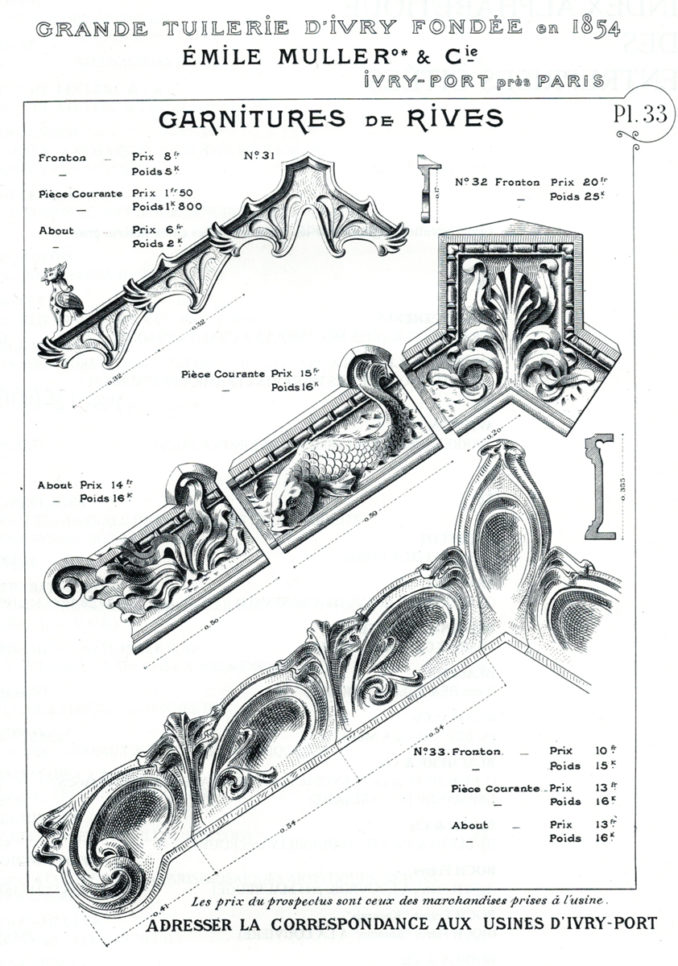

Catalogue n° 1, which includes building materials with bricks and tiles, is enriched with models in which Art Nouveau makes a discreet appearance on plate 33 with two models of verge tiles and pediments which frame a more traditional neo-Renaissance model. These are models not signed by an architect and were therefore purchased from an anonymous industrial artist.

Verge tiles from the Muller & Cie catalogue n° 1, pl. 33. 1903. Reproduced from La Céramique architecturale à travers les catalogues des fabricants, p. 167.

We will rely more readily on the plethoric catalogue no. 2 of 1904, which is mainly devoted to products for exterior and interior architectural decoration, but which also includes vases, pieces of art and trinkets. Many well-known artists can be found in this catalogue, and among those who worked in the Art Nouveau movement are the sculptors Pierre Roche, Ringel d’Illzach, Jean Dampt, Timoléon Guérin and Louis Chalon.

The Grande Tuilerie at Ivry — Part One: the Muller company

This series of articles dedicated to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry gives an overview of his work in the field of Art Nouveau. In this first article, we address the history of the company and the variety of his works. A second article will focus on Muller’s production in the Art Nouveau style, the third and fourth articles on Hector Guimard’s model editions and a fith on the fireplace sector.

Émile Muller (1823-1889) was born in Altkirch in Alsace, near Mulhouse. Coming from a well-to-do family, he completed his studies in Paris, graduating from the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufacture in 1844. He was then a professor of civil engineering for 24 years, starting in 1864.

-

Portrait of Émile Muller. Documentation center of the École Centrale Paris.

His involvement in the field of education is also shown by his participation in the foundation of the Special School of Architecture[1] and the (Paris) Free School of Political Science (now Sciences-Po). He also presides over the Society of Civil Engineers, where he will have Gustave Eiffel as his successor. Motivated by social ideas, after having built several public facilities, Émile Muller built a workers’ housing estate in Mulhouse in 1853, the first French experiment in decent family housing with gardens. He was also committed to protecting workers from industrial accidents.

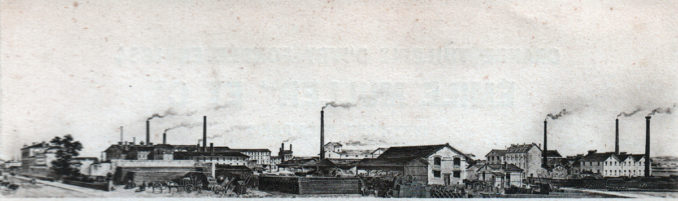

The following year, in 1854, Émile Muller founded a tile manufacturing company in Mulhouse, then a few months later bought a large piece of land to found the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry (the large Ivry tile plant), located on the banks of the Seine, on the Paris-Basel main road, near clay quarries in the southern suburbs of Paris. A showroom and sales room will be opened at a date that we do not know, but probably much later, at a more prestigious address: 3 rue Halévy, near the Paris Opera House.

General view of the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry. The front of the factory along the road facing the Seine river is on the left hand side. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 2, 1904, p. 1. Private collection.

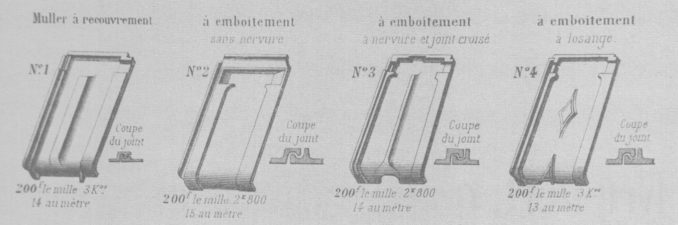

At the beginning the factory produces interlocking tiles using the process patented by the Gilardoni brothers, also from Altkirch.

Interlocking tiles. Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

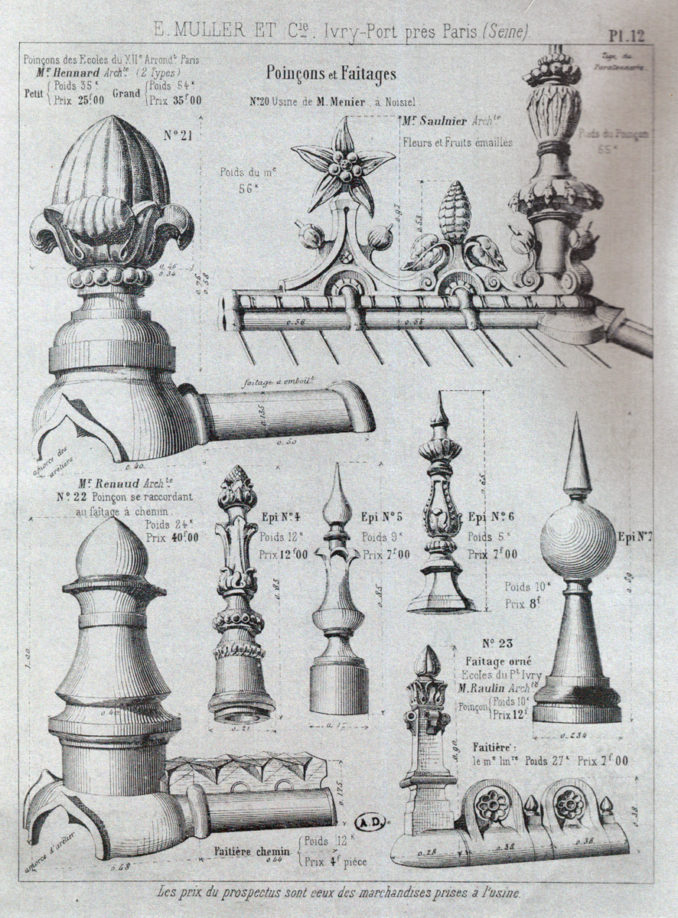

Roofing accessories are an important part of the production because they make it possible to customize a building. A number of special models are therefore created by several architects, which can then be edited.

-

Ridge models. Muller Catalogue Muller & Cie n° 1, 1895-1896, pl. 12. Coll. Library of Decorative Arts.

After starting the manufacture of enamelled products in 1866, the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry diversified its activities by producing raw and enamelled bricks and terracotta facade decorations, both raw and enamelled. Their composition allows them to be fired at high temperatures, making them waterproof.

Enamelled bricks Muller on an building entrance, Croix Faubin street, 10, in Paris. Photo by the author.

In 1871-1872, Muller provided his first large-scale architectural decoration for the Menier chocolate factory’s mill in Noisiel, the world’s first building with a load-bearing metal structure, designed by the architect Jules Saulnier.

Mill of the Menier chocolate factory at Noisiel Jules Saulnier architect, 1871. Photo internet.

Soon after, in 1875, the factory had 150 workers. Muller is of course present at the Universal Exhibitions, the one of 1867 and the one of 1878 where he ensures the success of architectural ceramics. At the 1889 Universal Exhibition, the domes of the Palais des Beaux-Arts and the Palais des Arts libéraux adorned with his turquoise-blue glazed tiles caused a sensation. He also presented glazed stoneware tiles for the first time.

Universal Exhibition of 1889, Palais des Beaux-Arts, architect Formigé, turquoise-blue glazed tile dome by Muller Photo National Gallery of Art, Washington.

For the first time, he also presented enamelled stoneware, including a copy of the Frieze of the Archers[2] from the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) brought back to the Louvre by the Delafoy expedition in 1885-1886. This frieze was later supplemented by a decoration of columns and flower boxes with lions for the winter garden of a private mansion in 1893, before being offered by catalogue and invoiced according to the number of archers requested.

Frieze of the archers, after the frieze of the palace of Darius I in Susa (Persia) of the Louvre museum. Vestibule of the building 11 rue des Sablons in Paris. Photo by the author.

It was at the end of the exhibition that Émile Muller died on November 11, 1889. His son Louis (1855-1921), known as Louis d’Émile, succeeded him as head of the company, whose name became “Émile Muller & Cie”. While keeping the production of enamelled bricks and mechanical tiles at the Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry, Louis d’Émile Muller opens up now fields of operations for the factory.