La Grande Tuilerie d’Ivry — Part Five: Muller “all fire and flame”

This series of articles devoted to the company of the ceramist Émile Muller in Ivry and its relationship with the Art nouveau movement concludes with a study centred on its production of modern style fireplaces. We thus offer ourselves an escape from Guimard’s creations since, to our knowledge, he did not ask Muller to create and even less to edit objects of the fixed decor. But we take the opportunity of this article to reveal the existence of fake fireplaces of a well-known model of Muller, one of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

The fireplace — the hearth — has always symbolized at the same time the place of domestic life and where the family unit gathers around when it brings a little comfort during the cold months of the year. In the 19th century, as the dining room became the core bourgeois reception room, the fireplace was an essential part of the decor, even if its functional role diminished as innovations progressed, such as the stove and then the salamander, which was adapted in front of its hearth, and especially central heating by radiators or hot air ducts. The fireplace was then reduced to a role of auxiliary or mid-season heating. However, neither the owners, nor the decorators, were ready to abdicate its presence in the house and its role in social representation[1].

Art nouveau style fireplaces

Art nouveau will be the style in which the formal aspect of the fireplace will literally explode. From 1895 to 1900, modern models were few, and above all not very visible because they were intended for private interiors, without mass production, with the exception of a few rare models presented in specialized magazines or official trade shows.

In the French sections of the 1900 Universal Exhibition, one can first come across fireplaces whose structure is still clearly neo-Gothic or neo-Renaissance but whose decoration is simply modernized, such as those by William Haensler, Georges Turck or the stand of the Professional Schools of the City of Paris. Other fireplaces are clearly Art nouveau in style, such as those in the dining rooms of the Épeaux and Dumas companys, both in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which reinterpret the naturalistic style of the Nancéiens in superabundance.

Fireplace from the dining room of the Dumas company, presented at the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition. Currently exhibited in the villa Cochet (Champagnes Pommery) in Reims. We don’t know the name of the ceramist who provided the insert. Photo author.

The fireplace presented by Louis Bigaux is more personal, as is that of Henri Bellery-Desfontaine, who gives pride of place to painting on its large hood.

But real stylistic innovations are also present at this exhibition, within the class 66 (fixed decoration of public buildings and homes) with the wooden fireplace from Pierre Selmersheim’s stand and that of Guimard in bronzed cast iron and enamelled lava where structure and decoration merge into organic forms.

Fireplace from Pierre Selmersheim’s stand, presented at the 1900 Universal Exhibition. Portfolio Exhibition of 1900 Decoration and Furniture, 2nd series. Forney Library.

For a few years, unique pieces as exceptional as the fireplace in the Masson dining room in Nancy will be produced for wealthy sponsors. They are obviously out of reach for the vast majority of bourgeois budgets.

Fireplace from Charles Masson’s dining room in Nancy by Eugène Vallin and Victor Prouvé, 1903, presented at the Ecole de Nancy Museum. Billed 4683.45 F-gold by Vallin, this fireplace probably never experienced an actual fire because from the beginning an electric resistance was placed in front of its hearth. Photo Philippe Husson.

The purchase of a fireplace, part of the fixed decor of a residence, only concerns owners in the case of a new construction or the modernization of an old dwelling, and not the tenants. This is why the furniture sets sold by cabinet making firms on catalogue usually do not include them. They do, however, offer them at widely varying prices. The Épeaux house, for example, which on the eve of the First World War still hadn’t managed to sell its 1900 exhibition fireplace, displays it in its catalogue at 4,800 F-gold.

Fireplace mantel from the dining room of the Épeaux company with an apple blossom design in Cuban mahogany and gold wood, presented at the 1900 Paris World Exhibition. Private collection.

The Art Nouveau glazed stoneware fireplaces

Even though marble workshops produced carved mantels on a production line in a few tirelessly repeated models, any fantasy or simply any novelty would be all the more costly as an expensive material must be crafted by a specialized worker. Manufacturers of tile products, manufacturers of glazed stoneware tiles, as well as industrial stove makers therefore quickly understood that, thanks to glazed ceramics and especially glazed stoneware, they could go beyond the simple supply of tiles intended to decorate mantelpieces to mass produce the mantels themselves, made up of a few easily assembled elements offering excellent thermal qualities. In a simple horseshoe pattern around the hearth and with only the obligation to surmount it with one or more shelves and possibly to provide space for accessories (shovels and pokers), they could give free rein to the imagination of designers. This type of article is then of a sufficiently interesting profit for most manufacturers to launch on the market models of glazed stoneware fireplaces of modern style. Below are a few examples.

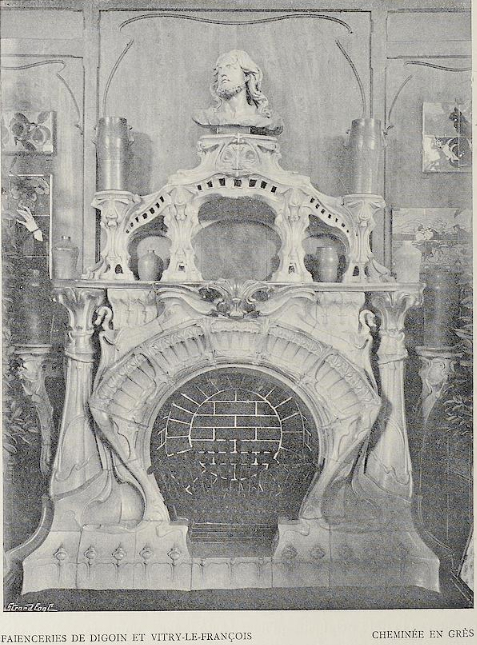

The earthenware factory of Sarreguemines, in the German-occupied Lorraine region, which for commercial reasons hid behind the names of its French plants in Digoin and Vitry-le-François, presented an Art Nouveau style glazed stoneware fireplace at the 1900 Universal Exhibition by the architect Victor Bury. The beautiful corolla motif of its central part is unfortunately weakened by the modeling of the rest of the mantel, consoles and shelves that the heat of the hearth seems to have melted away.

Fireplace from Sarreguemines in glazed stoneware, presented at the 1900 Universal Exhibition. Photo internet.

The same fireplace at the Sarreguemines earthenware museum. Photo from insming.centerblog.net

La suite de cet article est réservée aux adhérents. Veuillez saisir votre email et votre mot de passe ci-dessous.

Problème de connexion ?